Some requirements related to the environment, taxes, emergency response, and others remain unmet—highlighting zoning-enforcement challenges in the Berkshires.

∎ ∎ ∎

(CORRECTION 12/23/23: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described an inventory of toxic and hazardous chemicals used in the airport’s maintenance activities as a “snapshot-in-time” inventory. But according to a cover letter accompanying a June 1, 2023, filing with the town, it was a “list of toxic and hazardous materials used annually in the machine shop,” the information required by the special permit. This story has been updated to reflect this correction. The Argus regrets the error.)

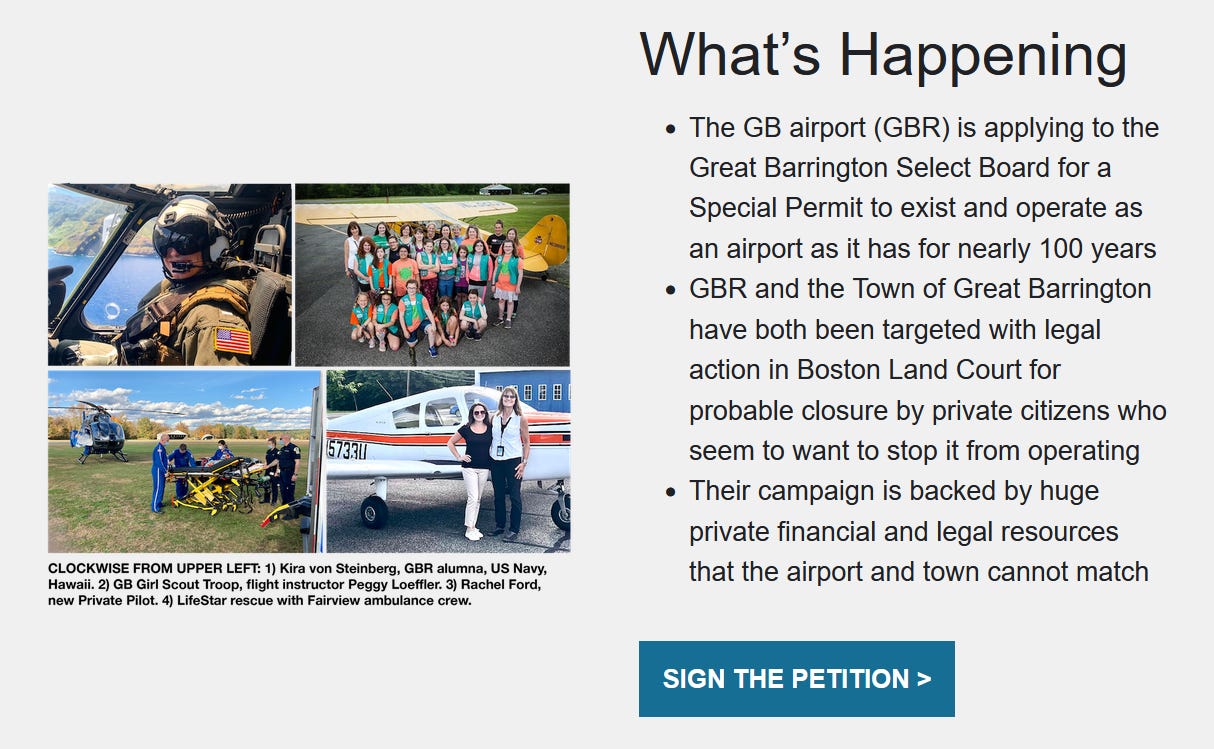

Here’s how the argument went in Great Barrington earlier this year: If the Select Board granted a special permit to the town’s beloved Walter J. Koladza Airport, effectively derailing a legal challenge that sought to constrain the airport’s activities, the airport would happily comply with any “reasonable conditions” the board imposed.

Select Board members took the airport and its attorney at their word: During a couple of months of hearings and debate—carried on alongside an often-contentious community discussion—the board, led by its chair, Stephen Bannon, insisted it could craft a permit that would protect the airport from legal action by neighbors, preserve purported benefits to the town, and, at the same time, attach conditions to address concerns about noise, expansion, safety, and environmental risk.

Indeed, the board concluded its official “findings of fact” this way: “The Select Board also finds that the conditions to be imposed will help to ensure that the overall benefits continue to occur and that potential adverse impacts are minimized and eliminated to the extent possible.”

It also included language emphasizing that each condition is “essential to mitigate the impact of the Airport” on the surrounding neighborhood, which includes protecting the vital drinking-water aquifer that sits directly beneath the airport’s 90-odd acres.

It’s been eight months since that permit [PDF]—with twenty-eight specific conditions—was approved. The decision was met with cheers and applause in the Town Hall meeting room from a crowd of airport boosters who rallied community support to pressure the board into its four-to-one “yes” vote—a notable reversal from a unanimous rejection a little more than two years earlier. But the airport’s compliance with those essential conditions—so far, at least—has been notably incomplete.

From failing to submit results of soil testing for contamination from leaded aviation fuel, to not providing clarity on property enrolled in a tax-saving agricultural-land program, to not submitting the number of based aircraft, the airport’s owner and operator, Berkshire Aviation Enterprises (BAE), has missed many of the permit’s deadlines to confirm various actions and deliver mandated reports.

In June and again last month, The Argus submitted public-records requests to the Town of Great Barrington seeking details of the airport’s compliance. Seven of the special permit’s twenty-eight conditions required action and related submissions by, variously, June 3, August 3, and November 3. (An annual informational filing is also due next February.)

But as of early December, Berkshire Aviation had fully complied with just two of those seven conditions, providing information [PDF] on flight paths, noise abatement efforts, fuel-tank-leak and dumped-fuel protocols, annual use of toxic and hazardous materials in its machine shop, and types of aircraft that use the airport—information required by conditions nineteen and twenty-two. Five other conditions with filing deadlines appear to have been ignored, or information not submitted to the town as required, based on information provided in the town’s response to two public-records requests.

In response, Great Barrington officials have, it seems, taken no action. On December 4, town officials reported they had received no additional information from Berkshire Aviation since its single June 1 filing.

(Great Barrington Town Manager Mark Pruhenski did not respond to a detailed email seeking comment. Select Board Chair Stephen Bannon was traveling this week and unavailable for comment.)

A lack of attention continues a well-documented history of Great Barrington’s government looking the other way when it comes to ensuring the airport abides by the same zoning mandates as others—a consistent municipal track record that goes back more than ninety years, to 1932, when the town’s first zoning bylaw made the year-old airport into a preexisting nonconforming use. (See, “The Airport,” an in-depth Berkshire Argus series from earlier this year.)

To date, according to a spokesperson for the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), the town has also not submitted the special-permit’s eight aviation-related conditions to MassDOT’s Aeronautics Division for approval—as required by state law. Because that hasn’t happened, those conditions—meant, in large part, to limit noise from the airport’s busy flight school during early morning and at night—have no legal effect.

According to one of the special-permit conditions, if the Aeronautics Division rejects even one of those aviation-related rules, the entire special permit becomes null and void—sending the whole matter back to square one.

Even if those flight-operations-related conditions aren’t officially on the books, the airport’s owners pledged to adhere to them—and appear to be doing so. That includes no flight-school training for two days each year: Memorial Day and July 4. And based on records provided by the town, there have been no formal complaints made to municipal officials with respect to the special permit’s modest time restrictions on takeoff-and-landing practice and six other conditions related to flight operations. Those include a ban on helicopter training and helicopter-sightseeing tours, no use of gliders or jet aircraft, and a ban on most drone flights.

Unmet conditions relate to environmental risks, taxes, and more

As detailed more fully in the attached “Berkshire Argus: ANNOTATED” document that provides context and analysis of the special-permit’s twenty-eight conditions, Berkshire Aviation has so far not provided the following (deadlines in parenthesis):

- Based aircraft: Provide a list/number of aircraft based at the airport. (June 3, 2023)

- Fuel-leak alarm alerts: Confirm implementation of a system to send alerts from the leak-alarm system that monitors the airport’s 20,000-gallon underground-fuel-storage tank, which sits above the aquifer that supplies much of the town’s drinking water. The system has an audible alarm that can be heard when the airport is staffed. (August 3, 2023)

- Emergency event response plan: Provide an “emergency event response protocol” to four entities: The Select Board, police and fire departments, and Board of Health. This is a separate requirement from its on-site underground-storage-tank leak protocol, which was submitted [PDF] as part of the airport’s only filing on June 1. None of these entities report having received new or updated “emergency event response protocols” from Berkshire Aviation. (August 3, 2023)

- Soil testing: Test soil at the airport for lead contamination and provide the results to the town within five days. Testing was done previously in 2017; a report provided by the airport showed only background levels of lead. Peer-reviewed studies that have found elevated blood-lead levels in children near general-aviation airports use data from airborne-lead testing; soil tests are more relevant to potential water contamination. (November 3, 2023)

- Property taxes: Submit a professionally prepared map “showing and including a calculation of the amount of land of the Airport currently enrolled in Chapter 61A agricultural-land tax program” to confirm a tax exemption that dates to 1981. (On December 15, the town’s assessor, Ross Vivori, confirmed his office had not received this information.) During a January 26, 2023, Planning Board hearing, airport attorney Dennis Egan said “only a very small portion of the airport’s property is in 61A.” Based on documents acquired by The Argus, from 2008 through the 2018 fiscal year, Berkshire Aviation claimed at least 52.6 acres as agricultural use out of approximately 90 total acres. Its 61A filing for fiscal year 2023 claimed 29 acres on two parcels, according to documents from the Great Barrington Assessors Department. (November 3, 2023)

ANNOTATED: Airport Special Permit Conditions (Click to download; click comment icons to display annotations.)

To those who opposed a special permit, the discovery that some requirements have not been met—and that municipal officials have taken no action—may not come as a surprise. Indeed, an attorney for a group of airport neighbors warned the Select Board in late February, “[Special-permit] conditions are never self-executing but require substantial municipal resources to monitor and enforce—particularly when an applicant has a track record of repeatedly failing to comply.”

On April 10, Ed Abrahams, the former Select Board member who asked the most detailed questions of Berkshire Aviation and its attorney during this year’s hearings, highlighted that concern moments before casting the only “no” vote. “Even if these conditions are enforceable,” he said, “the town doesn’t have the staff or resources to enforce them.”

The airport’s majority owner promised “to go above and beyond”

Rick Solan, the retired American Airlines pilot who launched his long flying career at the airport in the 1970s and became one of its owners in 2008, said at town hearings this year that he would agree to any conditions imposed. In January, during a discussion of conditions with Great Barrington’s Planning Board, he said, “I’m willing to do anything to get the permit. Whatever it takes.”

In a series of interviews in late 2022 and early 2023, Solan told me largely the same thing, with one caveat: He wouldn’t accept significant restrictions on BAE’s flight school. That includes, for example, limiting the number of training aircraft in the air simultaneously or similar restrictions floated in years past that were, in the end, not considered this year.

In early March, as the hearings were underway, I asked him about the enforcement concerns raised by Abrahams and others. At the time, Solan was unequivocal about his commitment—and very much aware of the attention then focused on the airport’s operations. “Right now I’m going to be under a microscope,” he told me. “I’ll be under a big microscope. So, do you think I’m going to even come close to testing the waters on that? No. I’m going to go above and beyond.”

(Solan did not respond to a message this week seeking comment.)

A respected flight school’s success lays the groundwork for trouble

Solan, 68, lives in northwest Connecticut and is a passionate educator: Many of his thirty-six years at American were spent as a “check pilot,” observing and training commercial pilots to safely fly some of the largest planes in the sky. He brought that interest back to Great Barrington—where he first learned to fly, taught by Koladza, the airport’s former owner and now namesake—and built a popular and respected flight school. It was firing on all cylinders during the pandemic, adding more flight instructors to keep up with growing demand for instruction due to both lockdown restrictions and the airline industry’s enormous demand for new pilots.

His focus has long been on training the next generation of pilots and providing the same opportunity for a good career that he said Koladza gave to him. So, not surprisingly, Solan inspired his son, Joe, to follow suit: The younger Solan, 25, is an experienced pilot and flight instructor who essentially grew up at the airport, has been its general manager since 2018, and is also pursuing an airline career. (Joe Solan was my instructor for an introductory flight lesson in July, 2022, detailed in “The Airport” series.)

But it was precisely that increase in locally intense flight-school traffic that further stoked complaints by airport neighbors who’ve said, almost without exception, that they don’t mind living near the airport. It was only the steady and substantial growth in activity—and a feeling that the airport’s owners and staff were not sufficiently responsive to their concerns—that fueled growing frustration and opposition.

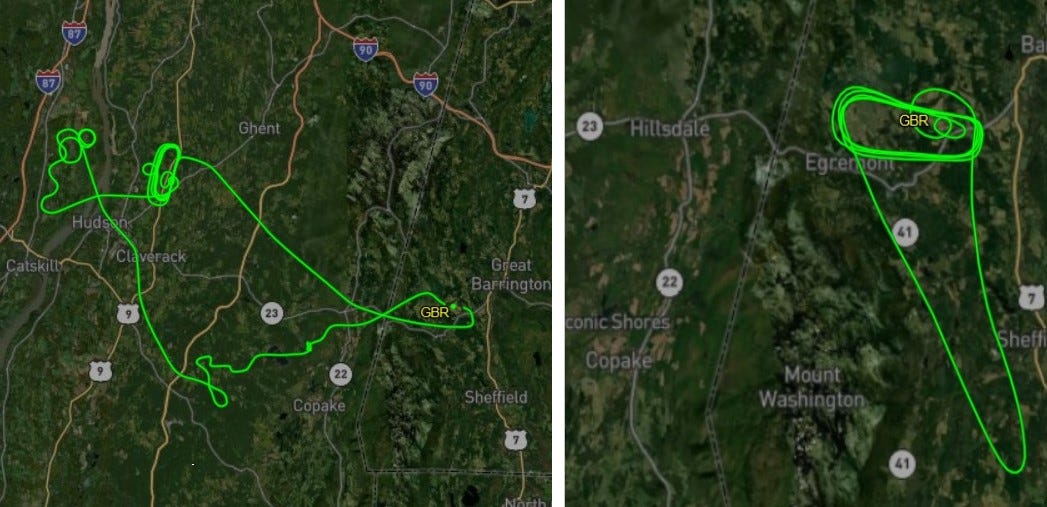

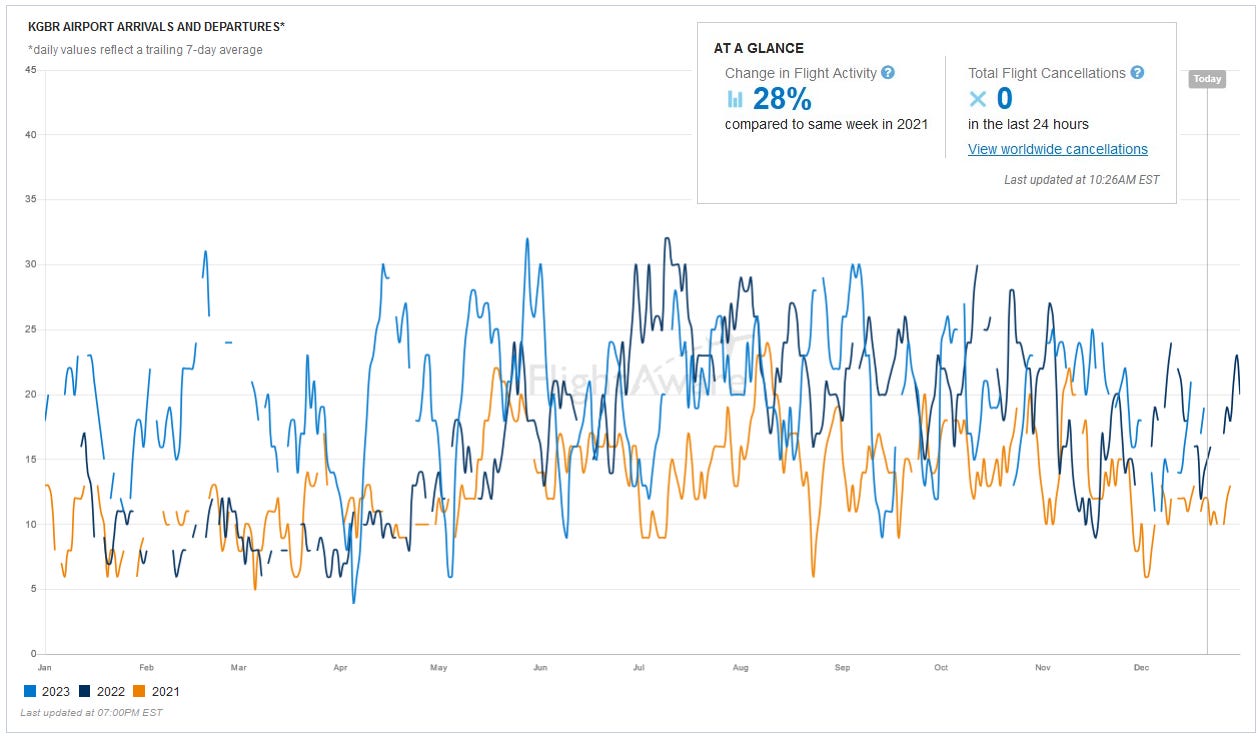

That trajectory is pronounced: An updated Berkshire Argus analysis of flight-operations data from 2020 through December 19, 2023, found that flight-school activity in Great Barrington continues to grow substantially, along with ongoing year-over-year increases in overall traffic.

According to data provided to The Argus by FlightAware.com—which counts the initial takeoff and final landing of each flight—BAE’s flight-school-related operations have increased by 217 percent since 2020. Overall traffic at the airport is up by 71 percent during that period. And over the last twelve months, flight-school activity has increased by 41 percent, according to FlightAware.com’s data.

These numbers are almost certainly undercounts of total operations: The data collected by FlightAware.com does not fully account for continuous-takeoff-and-landing practice by students circling in the local pattern.

During this year’s hearings and in written testimony submitted to the Select Board, neighbors said they didn’t expect the airport to comply with the terms of any special permit. They said its track record of prior compliance with, for example, the limits imposed by its preexisting nonconforming use, was already quite poor. In interviews with The Argus earlier this year, some also insisted that when they complained to airport staff about noise or nuisance flight patterns, they were targeted with repeated low flights over their homes.

But the airport’s owners and local pilots insist that doesn’t happen, and counter that BAE does its best to address noise complaints to the extent possible. That includes efforts to move some takeoff-and-landing practice to nearby airports in Hudson, New York, and Pittsfield, Massachusetts—which can be seen in FlightAware.com tracking data—and also relocating flight training to different locations to avoid concentrating too much activity, in a short period, over one area or home. Berkshire Aviation also points to a slight change in its flight pattern that asks pilots to edge north immediately after takeoff to avoid overflying houses along Route 71 in Egremont.

While detailing these and other efforts in a July, 2022, interview, airport co-owner Jim Jacobs conceded there’s a limit to what’s possible. “We are an airport. We do make noise,” he said.

(DISCLOSURE: My home is approximately four miles northwest of the airport at the New York State border and outside the airport’s local flight pattern. Still, I see or hear occasional aircraft transiting to and from the airport.)

The long, winding road to a special permit

Ignoring zoning rules has a remarkably long history at this airport, where many come to learn to fly and others just enjoy the chance to sit at picnic tables and watch the small, piston-engine airplanes take off and land. Indeed, Great Barrington’s is an increasingly rare sight: A small, country airport with no security fences, a run-down, throwback office with walls plastered with photos and flight memorabilia, and rookies and aviation veterans talking shop in the small-but-comfortable pilot’s lounge. But however quaint, all of that is tucked inconveniently into a residential neighborhood.

Since the 1930s, the airport consistently received special treatment from the town’s elected leaders—who, particularly in the airport’s early days, overlapped substantially with the airport’s ownership group of local notables. That established a pattern: With just one exception—a short-but-intense battle over the use of glider-tow planes around thirty years ago—until a few years ago, the airport operated as it wished, ignoring zoning rules with something ranging from disinterest to winks and nods from municipal officials.

The airport was bought and expanded during World War II by James F. Tracy, a recreational pilot who at the time of the sale was the popular chair of the Great Barrington Select Board. Another Select Board member—an engineer—was hired to build the airport’s upgraded runway in 1957. In both cases, work was done without necessary permits or zoning approvals. (Remarkably, the Town of Great Barrington provided the heavy machinery needed for the runway project.) And under Koladza, a former test pilot who moved to Great Barrington and ran the airport from 1945 until his death in 2004, operations were further expanded, and new buildings constructed, without approvals.

After Koladza’s will bequeathed the airport in 2008 to Rick Solan and three others, the new owners told reporters about ideas to add a few things, from expanding the flight school to perhaps opening a small restaurant. Neighbors feared there were plans for even more substantial expansion. That’s why they strongly opposed two attempts by the airport, in 2017 and 2020, to earn zoning approvals for six new hangars and secure the golden ticket: A special permit to operate as an official, zoning-and-town-endorsed airfield.

In the first attempt, the application was pulled after months of contentious hearings that included hours of testimony about the impact of already increasing local flight operations. And at the conclusion of the latter, in 2020, the Select Board voted unanimously that any growth “beyond the current level of use and type of operations” would be detrimental, rejecting both new hangars and an aviation field special permit.

To Land Court—and then back to the Select Board

But to some, the defeat of the 2020 special-permit application did not provide satisfaction. Led by Seekonk Cross Road resident Anne Fredericks—a former Wall Street trader who has lived near the airport since the early 1990s—and her husband, the lawyer and investor Marc Fasteau, a group of neighbors sought zoning enforcement. They argued the airport continued to operate well beyond what was permitted under its preexisting nonconforming status—especially a flight school that had grown ever busier, with training aircraft circling the airport’s flight pattern with an intensity that disturbed the neighborhood in exactly the way the Select Board had just ruled would be unacceptably “detrimental.”

The town’s Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) strongly disagreed, dismissing their complaint with a unanimous vote. So, in May, 2022, the neighbors went further, bringing the matter to state Land Court—where it appeared to be receiving a more sympathetic legal ear.

As that case advanced toward what looked increasingly like a ruling that would clip the airport’s wings, Solan and Jacobs, the airport’s minority partner, decided that perhaps the third time would be the trick: They again applied for a special permit to become a conforming airfield under the zoning bylaw, but with no controversial plans for new hangars or anything else tacked on. They proposed some conditions to address noise complaints and hoped a win at Town Hall would drive a stake through the Land Court case — which it later did.

This time, airport fans rallied the community with a new message: The neighbors didn’t just want to limit the airport’s operations or block new hangars, they said, but aimed to “shut down the airport entirely.” That claim probably overstated things—even with an unfavorable Land Court ruling, the ZBA seemed inclined to provide specific zoning approvals if needed. But, the argument went, not without the possibility of more legal scuffles.

As an organizing strategy, it worked like a charm: They gathered thousands of petition signatures—most from outside the area but many from Great Barrington—and submitted them to the Select Board. When the hearings began, airport supporters packed the Town Hall meeting room while hundreds more attended via Zoom and even more in a local theater’s screening room. In front of the Select Board’s five members—two of whom were new to the board since the airport’s failed 2020 application—around 75 people applauded loudly at every pro-airport comment.

That a special permit would be awarded was never seriously in doubt, though the extent of attached conditions was a wild card. In the end, two board members who voted no in 2020, Bannon and Vice Chair Leigh Davis, helped it across the finish line with their votes. (A special permit requires four votes, not just a majority.) Why the change? When Bannon was asked at one point, by Abrahams, how the 2023 application differed from the one Bannon and the full board rejected in 2020, he replied, “The Land Court case.”

Minutes before the vote, Davis raised concerns about enforcement, which followed her earlier line of questioning about the need to establish baselines to use when evaluating the airport’s level of activity in the future. “I want to make sure there’s a way to enforce this,” she said, but received no assurances from town staff other than plans to fill the long-vacant role of assistant-building inspector. (Davis told me in May that this year’s application was “a clean slate” and it was “unfair” to compare it to the 2020 application.)

The town’s—and region’s—challenge with zoning enforcement

It’s not just the airport’s special-permit conditions that aren’t being closely watched. It’s long been difficult for understaffed building departments in Great Barrington and other southern Berkshire towns to keep up with permit applications and inspections, even without the added burden of tracking a variety of specific conditions. In that context, the notion of proactively monitoring compliance can seem almost laughable: Most often, zoning enforcement only happens if and when someone complains.

But even that’s no guarantee of action. Across the region, building departments are stretched thin. In large part, that’s because it’s hard to attract skilled inspectors to a challenging, often thankless job, particularly when opportunities to work as a contractor in the hot Berkshires housing-and-renovation market can deliver more income and fewer headaches. (Typically, building inspectors in Massachusetts must have at least five years’ experience “in the supervision of building construction” and then pass a variety of certification exams.)

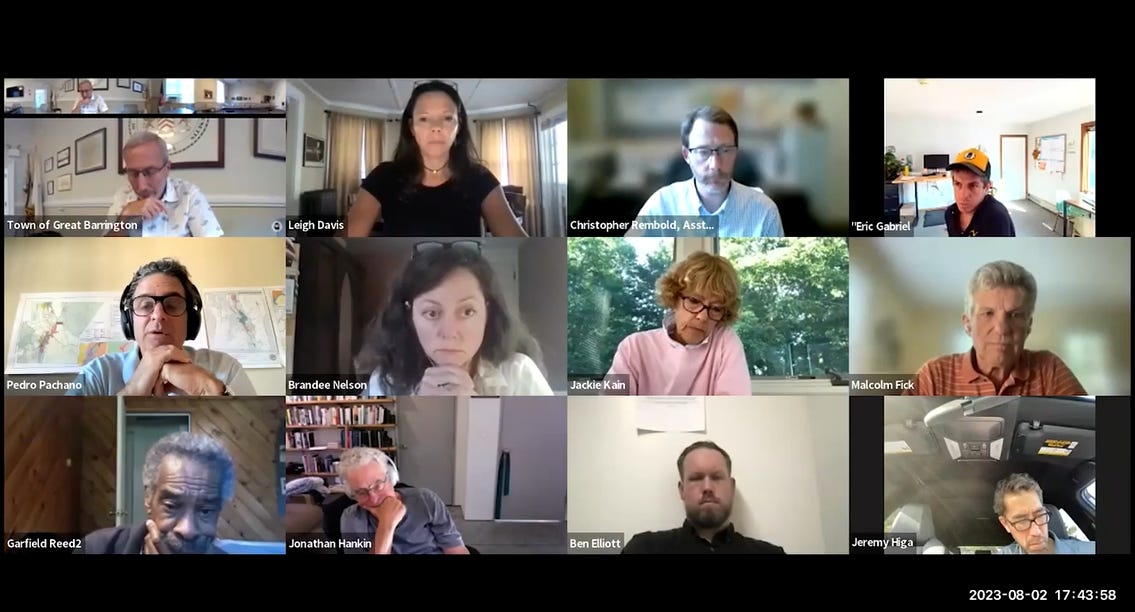

All of this has been on the radar of Great Barrington’s Planning Board. It held a joint meeting with the Select Board on August 2 that included discussion of enforcement deficiencies. Driving the conversation was the Planning Board’s frustration that significant time and energy are put into site-plan reviews and other zoning-related efforts to guide development according to voter-approved zoning rules—only to frequently see their work, as well as legal requirements, ignored or violated. The board’s members asked the Select Board to look into ideas for improvement.

Brandee Nelson, the Planning Board’s longtime chair, summarized her concerns concisely: “How do we assure that site plans and special permits are implemented consistent with the approvals that are granted?” she asked. (In January, the Planning Board voted unanimously to recommend the Select Board approve the airport special permit.)

Nelson noted that the retirement this year of Great Barrington’s longtime Building Commissioner, Edwin May, could present an opportunity. “With the turnover that’s going to be happening in that department,” she suggested to members of the two boards, “there’s an opportunity to set a tone around the importance of compliance around the various conditions of permits … and set a standard that will be a little different from where we’ve been.” And while she was “hesitant to put more on the town’s Building Department,” she said “it’s a natural place” for resources to be invested.

Bannon suggested the Select Board could put the matter on its agenda later in the fall and discuss it with town staff. At the time, Great Barrington’s Building Department was nearly defunct, with May retiring and a second position long empty. But Bannon also said he wanted to be sure Great Barrington didn’t earn even more of a reputation as a place where development is hard.

There has not yet been a public agenda item for that discussion. Still, the following month, Great Barrington crafted a multi-town partnership with Lee, Lenox, and Stockbridge to build out a single, Great Barrington-based department. (That agreement was approved by the Select Board on September 11.)

Led by new Building Commissioner Matt Kollmer, who spent six years as the assistant-building inspector in Great Barrington, it will have a total of four inspectors. At a salary of $120,000, Kollmer will oversee three inspectors and their work across all four communities.

It’s unclear how that’s going; the town has been promoting job listings for the $70,000-a-year local-building-inspector jobs for several months. Pruhenski, the town manager, did not respond to an emailed question this week about the new Building Department. But in September, he told Select Board members the new arrangement could, once fully staffed, free up Kollmer to work on more involved and complicated zoning matters.

Last month, Pruhenski also told the Massachusetts Municipal Association (MMA) that the staffing challenge for local building departments was at a crisis point. After failing to fill Kollmer’s former role for eighteen months—he left his Great Barrington gig to work as a building inspector in Lee and Lenox as well as Stockbridge—the town needed a new approach. “There’s just a very limited pool of candidates, but in some cases there is no pool at all of qualified candidates,” he told the MMA.

It follows a growing trend in the Berkshires of tackling municipal budget and staffing challenges with regionalization of services, from human resources to public health and health-code enforcement (though not education). Still, how Kollmer will manage a four-town workload and staff is complicated, perhaps, by additional commitments: He’s also currently the building inspector for the towns of Alford and New Marlborough and the assistant-building inspector in Egremont, where he fills in when its inspector is unavailable or has a conflict.

How a building inspector, who is the zoning-enforcement officer in each town, navigates the intersection of complex building codes, contractors, zoning bylaws—and sometimes, political and other pressures—has an interesting historical connection to the airport. In 1990, William Snyder, then Great Barrington’s building inspector, issued a zoning-enforcement order to rein in use of loud, droning, glider-tow planes that were driving airport neighbors out of their minds and homes. But after a contentious ZBA hearing on the matter in front of 150 residents, and public statements by members of the Select Board—Snyder’s employer—in support of the airport’s all-weekend-long glider activity, he suddenly reversed himself and dropped the matter. (Koladza eventually sent the gliders packing.)

Snyder must have smarted from the experience: With some irony, perhaps, he resigned in 2001 after years of grumbling by members of town boards that he was—for some mysterious reason—unwilling to consistently enforce all provisions of the zoning bylaw.

Questions remain about monitoring flight operations

As for the central challenge facing Great Barrington’s municipal government on the airport matter today—how to enforce the special-permit’s commitment to keep the airport’s growth rate to zero in the face of what data show is steady growth—that remains a significant unknown.

The Select Board did not require use of relatively inexpensive technology tools available for accurately counting and tracking flight operations, including continuous-takeoff-and-landing practice, known as Noise and Operations Monitoring Systems (NOMS).

The airport’s attorney, Dennis Egan, told the Select Board there’s no way to track flight operations at a small airport and that, in any event, the town has no authority to regulate that activity. He also separately claimed in court filings and in front of the board that the airport is entirely exempt from zoning—something the Land Court might have addressed had that case proceeded—so the airport chose to “voluntarily submit to zoning” with its special-permit application to attempt to find a resolution.

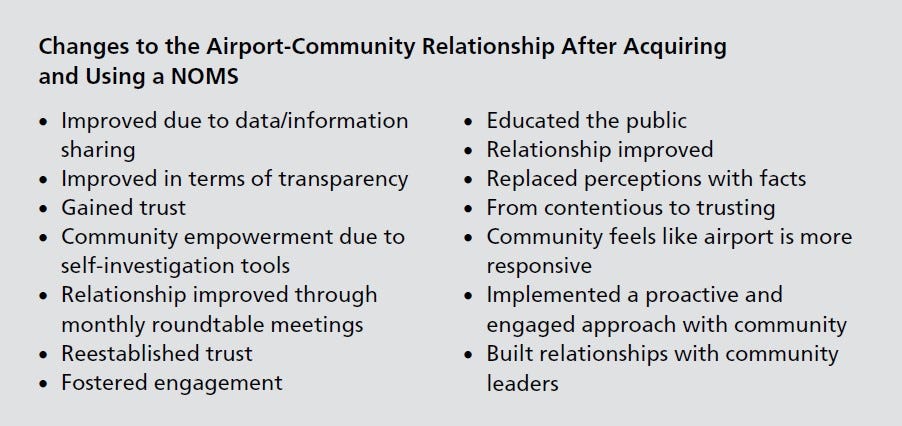

But a NOMS could be useful for both the town and the airport nonetheless—though it’s too late to require one. These systems use several means to track flights to, from, and around an airport, providing municipal leaders, neighbors, and airport staff with useful data. Issues can be addressed with hard facts and information, not speculation or accusations. (If any pilots were deliberately harassing a complaining neighbor, it would be easy to see and address, or demonstrate that a complaint was not backed up by the facts.)

Last year, a study by the National Academies of Sciences’ Airport Cooperative Research Program found that the systems were beneficial: “NOMSs are used to respond to community noise complaints and provide stakeholders with information about aircraft activity and noise, thus fostering trust and transparency,” the report said. Those communities where the technology is used, the report concluded, “replaced perceptions with facts,” and relationships between airports and their neighbors went “from contentious to trusting.”

What’s next?

After all the effort, drama for the community, time and resources of town government, and legal expense—not to mention countless hours spent by those who rallied to advance the airport’s application—it’s unclear why Berkshire Aviation would ignore several modest compliance requirements. Combined with the town’s disinterest in enforcement—so far, at least—it leaves open many questions about the future. Failing to meet special-permit conditions may also seed the ground for new legal battles.

Ultimately, it will be on town officials to take action—or not. The four-town Building Department is still nascent; it remains to be seen whether it will have greater ability to track compliance with special permits—or approved site plans, for more mundane construction matters—and robustly pursue enforcement action as needed. Or, more generally, if it will be given a clear mandate and sufficient resources to satisfy the Planning Board’s request.

From where such a mandate might come also remains unclear. When the Planning Board and Select Board met in August, responsibility for improving zoning enforcement seemed like a hot potato no one was particularly eager to pick up. The Planning Board has no enforcement authority, so it can only look to the Select Board, and the municipal government its five members direct, for action.

When I spoke in late spring to Davis, the Select Board vice chair, about her concerns related to enforcing the conditions she had just voted for, she didn’t sound eager to take on that challenge. “In terms of enforcement, I’m not really sure how that would look,” she told me. “I would just hope that someone’s accountable and the proper procedures are followed.”

∎ ∎ ∎

Read “The Airport,” an extensive Argus series about the airport and the history of Great Barrington.