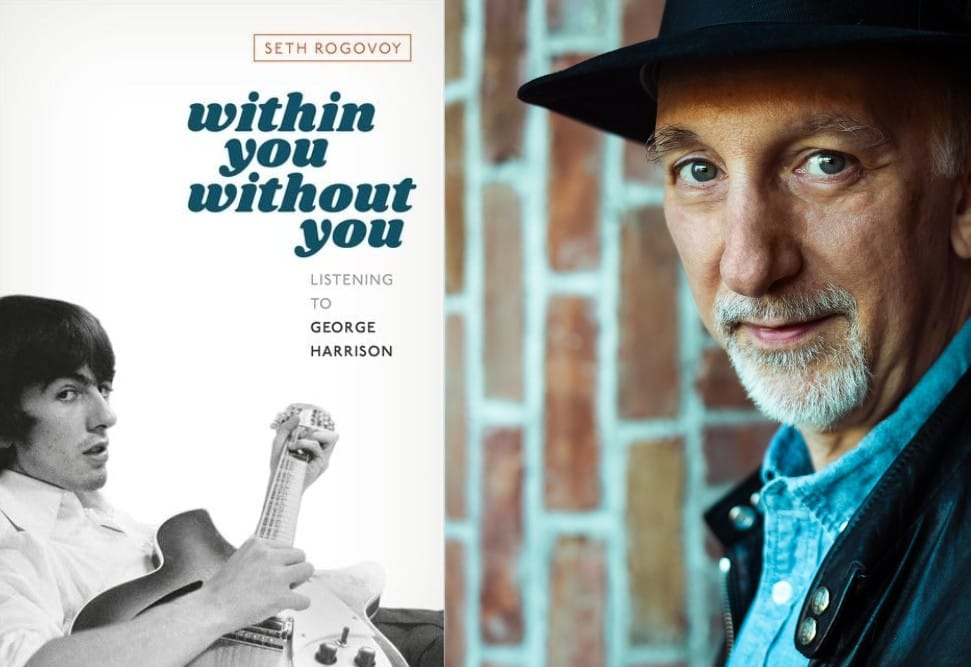

AUDIO: In new book, Berkshires rock critic Seth Rogovoy explores the music of Beatles guitarist George Harrison

"Within You, Without You: Listening to George Harrison" is a deep, passionate dive into the music of the so-called "Quiet Beatle."

∎ TRANSCRIPT ∎

BILL SHEIN, EDITOR, THE BERKSHIRE ARGUS: When longtime rock critic and music journalist Seth Rogovoy was in high school, he suggested to the editor of his school paper that he contribute a few music reviews, and the editor readily agreed. If he didn't already know, Rogovoy quickly learned that people have strong opinions about the music and bands they love, because after he published a negative review of the Eagles iconic 1977 album “Hotel California,” an outraged Eagles fan chased Rogovoy down a school hallway.

He survived, obviously, because many know Rogovoy from his decades of work for media outlets across the Berkshires, New York’s Hudson Valley and beyond. His weekly Rogovoy Report, which airs on northeast Public Radio and is accompanied by a popular Substack newsletter, offers an indispensable guide to what's worth seeing, hearing and thinking about in our region, and another newsletter, Everything is Broken, provides readers with an eclectic mix of Rogovoy’s music reviews, his take on books and movies, and thoughts on the writer's life and the world writ large.

His new book, “Within You, Without You: Listening to George Harrison” is, as he makes clear at the outset, not a biography of The Beatles guitarist, though it is rich with background and stories about the lives and music of Harrison and his little-known bandmates, a few blokes named John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr. I think I’m pronouncing their names correctly.

Rogovoy said he spent five years researching and writing the book, which examines George Harrison’s music and influence through a close listen to songs he co-created with The Beatles and others recorded over his three-decade, post-Beatles career. In this podcast conversation, Rogovoy argues that while Lennon and McCartney wrote most of The Beatles’ songs. It was Harrison’s musical skill, creativity, and inventiveness that gave the group its distinctive sound.

We also talked about the nerdy pleasure of deconstructing a song to glean insight into how musicians painstakingly assemble what is later presented to listeners as the finished product. His passion for this work is clear: At one point, he spent ten fascinating minutes describing the vital contributions Harrison made to the song, A Hard Day’s Night, a detailed analysis of guitar licks and solos that lasted four times as long as the entire two-and-a-half minute Beatles song.

His enthusiasm and his critical eye will have you queuing up Beatles songs and George Harrison tunes and listening to them in a whole new way.

My conversation with Seth Rogovoy about his new book runs about seventy-five minutes.

BILL SHEIN: You say up front in the book that this is not a biography of George Harrison.

SETH ROGOVOY: First line. In the first line, just to make it clear.

[LAUGHTER]

BS: Though, obviously, through the course of the book and talking about the music, there’s a lot of information about him, about The Beatles, and his life and evolution as a musician. So for people who may not know very much about him, other than as a member of The Beatles, who was George Harrison? What’s the thumbnail sketch of him as a person and musician?

SR: Well, it’s a great question, and, you know, I can answer it as in thinking about, why was I? Why am I? Why was I? Why am I drawn to him to the extent that I would want to write a whole book just about focusing in on him, not a biography, but an appreciation. To me, he’s by far the most fascinating character of the four of them. I mean, they were all amazing, but I want to say now that one of the things that I learned in this intense last five-year period of working on this book is, if anything, my appreciation for the other three Beatles was enhanced exponentially. I mean, I always knew they were good or great, always loved and still think Ringo is just an incredible musician. I won’t even say drummer, but the way he plays the drums just like the way George plays guitar, these are unique approaches to their instruments and unique approaches to how their instruments fit in with the greater group in the band.

So, George is just such an interesting, fascinating character, and I think I was drawn to him for a number of reasons. First of all, he’s kind of—he and Ringo, they’re the underdogs. I mean, you’ve got Lennon and McCartney, the greatest songwriting duo of the 20th century. They’re certainly in league with the pre-rock songwriting duos like Rodgers and Hammerstein and the Gershwins. You know, when it comes to rock music, it’s Lennon and McCartney—just incredible. But George on his own was fascinating, like I said. So he was, in a sense, the underdog. And I’m, I’m always rooting for the underdog. I’ve been a lifelong New York Mets fan…

BS: So explain that a little bit more. So an underdog in what way? And is it a retrospective look at him as an underdog?

SR: I think he always was the underdog, okay? And this is just one of several reasons why I was really drawn to him. And you know, even George himself came up with this term for him. He and Ringo, he would call them “the economy class Beatles.” So Lennon and McCartney are flying in first class, and George and Ringo are on the plane—but they’re flying coach. And it’s understandable, because historically, the evolution of The Beatles began with previous groups where Lennon and McCartney were the original members, and bit by bit, those groups morphed and morphed and morphed until they became The Beatles. And even in the early Beatles, you had a few other players and a few left, and then they acquired a few more. So in that sense, people, I think when they think about The Beatles, they think about John Lennon, they think about Paul McCartney. I don’t know how much they think about George Harrison. They know he was a member. They certainly know Ringo, because he’s adorable, and he’s still out there every summer, touring with his all-star review—S, T, A, R, R, Ringo, Starr.

So those are the things that make George somewhat of the underdog. He was the underdog too, because as much as he showed talent for singing and especially for songwriting over the course of the short eight years that The Beatles had as a recording band. And it’s just boggles the mind to think that all that happened in the course of eight years. Because when we have bands now that have been together going on sixty years, and certainly dozens and hundreds of bands that have been together twenty years, thirty years, forty years. You know, these guys were together eight years, and they’re still The Beatles. They’re still the greatest ever. And maybe that says something about being together.

So the other things about George that that I found fascinating are, I’m always drawn to music and spirituality. It’s hard for me to say why I and I only I realize this when I look back and see the choices I’ve made in terms of what projects have I dug deeply into. This is my third book. My first book was about klezmer, which is a contemporary music based on a 19th century music of Eastern European Yiddish speaking Jews, primarily the wedding music, which served a spiritual function. So that I responded to very strongly my particular take on Bob Dylan, and that I wrote about in Bob Dylan, Prophet, Mystic, Poet, was how Jewish Bob Dylan’s songs really are how much they engage with Jewish texts, scripture, liturgy, themes, philosophies. So that’s what I dealt with there and here. Although I’m not dealing only with the spirituality, it certainly is an essential aspect of George’s personality, certainly of his music once he, you know, once some switch gets turned on and he starts getting into Indian music and studying with Ravi Shankar. And Ravi Shankar explaining that this particular, this northern Indian or Hindustani classical music, is a music which is inextricably linked with Indian spirituality, with Hindu spirituality. So I was always drawn to that aspect of George too.

He was incredibly funny and wry. And I don’t know if I would if acerbic is the right word, but he certainly, from where he stood in the group, in The Beatles, he always seemed to have—he seemed to be a little bit separate and watching and winking, winking at the listener, at the viewer, at his band members, in a way that was a little bit different. I don’t want to say he was insincere, because in his songs that he wrote he was incredibly sincere, but he had a really hard time believing in and responding to Beatlemania, the just over the top, fanatical worship of The Beatles as almost deities, the behavior, the extreme behavior of a certain element of Beatles fans disturbed him. He didn’t think that they should be the objects of veneration and worship. And it frightened him because he saw that that veneration was just the flip side of the coin of hatred, which The Beatles experienced that a number of times during that short time they were together, a number of things caused that. The truth is that they had constant death threats phoned in. There were bomb threats phoned into their concerts. There were people would throw stuff at them on the stage, not because they were, like, mad at them, but because, like in some interview, one of in an English interview, one of them said that his favorite candy was a jelly baby. Now, a jelly baby in England is kind of like a gummy. I’s not a jelly bean. But in America, that got translated to Jelly Bean, which is a hard candy. Yeah, so they get up on stage, and people were whipping jelly beans at them. And you know, that could put out an eye, as my grandmother would say.

BS: You know, it’s interesting. A couple things you said there that I read in the book—many times where that awareness that he had, that you described it as standing aside a little bit just now, but that, that awareness of what was happening and the concerns that you described. And you’ll have to refresh my memory on which of the films they did that had some scenes in it where they were being attacked, and that was pretty early, right?

SR: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

BS: Just, just talk a little bit about that, yes.

SR: So in the movie, Help!, the whole premise of the movie is that there’s some gang that that wants a ring that Ringo is wearing because it belonged to their tribe or has some kind of magical, mystical powers. And Ringo can’t get it off his finger. So basically, the entire movie is just this kind of farcical thing where The Beatles get chased. And it’s really like a metaphor for Beatlemania, and you see them getting chased all over the world. They go to, I think they’re in Central Europe, they’re in the Bahamas. They’re in England. They’re elsewhere too. And there’s a scene in that movie where they’re all living together in adjoining—they have front doors that are separate, but they all open up into one big house that all four of them live in and there’s a home invasion by this gang to, you know, mess with all of them. And it’s shocking, because in 1999 George Harrison fell victim to a home invasion to the point that he was almost killed. And I don’t know how many people realize that, and we all know that John Lennon was murdered. Which also, I mean, George was always aware of the potential for violence that it was in these comic, farcical movies.

BS: Yeah, that’s interesting, because when I read that in a couple different places in the book, that was part of the awareness that came across. He was aware of that. And then in the portion of the book where you write about the 1999 attack, you know, those threads all came together. And I think you’re right. A lot of people don’t remember, I didn’t remember the details of that attack. Who was it that attacked him?

SR: I think the conclusion was that this person was insane, I guess that’s a legal term. In other words, not responsible for his actions due to some kind of mental illness, I think in a similar way to what Mark David Chapman suffered from, kind of a personality disassociation. He thought he was John Lennon. This guy thought he was George Harrison or was being told by some beings that he should get rid of George Harrison, or something like that. So, you know, he was, he was a disturbed nobody who somehow was, you know, fanatical enough to get by—there was security, obviously, in 1999 where George was living in his home. This was in Friar Park and Henley on Thames in England. You know, we all know John Lennon just got shot on the sidewalk out in front of The Dakota apartment building across the street from Central Park in Manhattan, although there was probably a security guard right there. Anyway, so that was the attack on George, which he amazingly survived, because he was stabbed multiple times in the lungs. He collapsed his lungs. It didn’t look good for a number of days.

BS: And the attacker—was it his wife who hit him over the head?

SR: Yes, it’s actually, you know, he went downstairs to see what the noise was. They heard broken glass or some rummaging, because the guy broke through a window, and the guy had a big machete or a huge knife or something. George tried to fight him off, but the guy had this huge knife, and it was kept stabbing him, and so was George’s wife, Olivia, comes to the top of the stairs and sees what’s going on and runs down to try to help, and she grabs a big lamp and bashes the guy over the head so that the photos the next day that are in the press of the perpetrator show that he got beat up pretty badly. And that’s primarily, I mean, George put up a struggle too, as long as he could. But then, you know, Olivia saved George’s life.

BS: You had some quotes from him in there about what he was thinking about as this was happening, and the connection to his spiritual evolution, right? If I’m remembering that right, but I want to ask you, as we sort of shift to talk a little more about the meat of the book, which is about the music. So you said that most Beatles fans see their work as the work of a collective. They may think of Lennon and McCarthy as the songwriters, but they still just see them as The Beatles, and don’t pay as much attention to the individual parts who wrote the song, who played, which parts, necessarily. But you know, in reading the book, the excitement that comes through in the way that you pull all of those pieces apart. You know, the intricacy of the individual songs, the lyrics, the grammar, even the individual guitar licks. So just describe for people who aren’t music critics, people who just enjoy music, what is it about that approach and that level of understanding that that enriches the experience?

SR: So you’re right. I think the vast majority of people who listen to The Beatles hear The Beatles and just hear this sound that the group makes, and they don’t take it apart and analyze it and figure out, why does it sound the way it sounds. That’s kind of a geeky, nerdy thing that fanatics, or ardent Beatles fans will do, and so that’s probably, I don’t even know if it’s five percent of the people who listen to The Beatles. Maybe it’s one percent.

But anyway, I’m always trying to dig and understand how different music that I like gets put together. It’s the way I listen to music, I guess, given my profession, given my training on the job, and how I’ve approached music for so long, and in particular in I could talk about specifically in this case, because, like I said, when I really started listening to The Beatles, I could not help but hearing and noticing how much the music relied on and depended upon what George Harrison was playing. You know, The Beatles have a sound, and you can think of any number of songs and how certain sounds really stand out because they’re catchy, because they repeat in in ways that make you instantly respond to them, especially like if you just hear that, you know it’s The Beatles.

And to a large extent, it was what George brought. So Lennon and McCarney would bring in a song and introduce the song to their bandmates, and people would piece together the arrangement, with the help of their producer, George Martin, who was really the fifth Beatle, certainly in the recording studio, who had ideas and who helped them along the way, brought in outside musicians, an orchestra here, a brass player here, something like that. So you hear a song like, like—on the drive over here, I was listening to The Beatles Channel, as I have been for five years. I still listen to it all the time. You know, they played The Beatles song “I Feel Fine,” which is, you know, a pretty well-known song, and it’s got that down down and a Down Down, Down Down, Down down, and a Down, down, down, down. Boom, butter Bum Bum Bum bum.

[MUSIC: Clip of “I Feel Fine”]

That lick, or riff, or whatever you want to call it now, Lennon and McCartney—I forget who, whose song it actually was—you know, one of them wrote that song, wrote the chords, wrote the lyrics. They bring it in, and it’s George’s job in The Beatles to come up with that stuff, the what I sometimes call the punctuation or the emphases or the commentary. So you’ve got the melody line that Paul McCartney, for argument’s sake, wrote, you got the lyrics that he sings. But then there’s that other stuff that makes it more interesting, that makes it more catchy. And not exclusively George Harrison, but to a great extent, certainly in the first half of The Beatles career, when they were basically, you know, a four-piece band, and the music was, to a large extent, guitar music. It’s George who’s coming up with all of these, who’s composing these licks and riffs that really make that song and give The Beatles their sound that especially once he picks up the 12 string electric Rickenbacker guitar, which is the sound, that kind of jangle sound. I mean, we still have to this day, people talk about jangle rock, and new bands play jangle rock, and it all goes back to what George Harrison was playing once he picked up that twelve-string electric guitar that that sound that Roger McGuinn made, the trademark sound of The Birds—who were the American Beatles, fashioned as the American Beatles. And he was a great guitar player. And he heard George, he saw in the movies what guitar he was playing, and he just picked it up and ran with it and made it a whole big thing for himself.

BS: Actually, that’s a great lead in. What I’d like to do is take some songs that you wrote about in the book and dig into them just a little bit. So that actually leads right into the first song on the list has exactly what you’re describing. And that’s “A Hard Day’s Night.” You wrote about the very first chord at the beginning. So let’s talk about that.

SR: Yeah, so I think most people, or many people—and if you don’t, you should pause this and take a listen to the first note, or the whole song of “A Hard Day’s Night.” It begins with this just clanging chord which nobody’s ever heard in history, because George has made up this chord, this series of notes that get all played together

And also George Martin, along with him, has assigned some other sounds to go along with this chord, which becomes the most distinctive chord and the most distinctive sound. If you had to pick one second of Beatles music to represent all of it, I would argue it is that opening “carang” of “A Hard Day’s Night”—I can’t sing it because it’s impossible because it’s a chord, it’s not a note, but it has such a stunning effect because it’s a little odd to the ear, because it’s not just a C chord or a G chord, which just are pleasant chords. It’s not major, it’s not minor, it’s almost a little discordant.

[MUSIC: Clip of opening of “A Hard Day’s Night”]

And what happened was they had the song A Hard Day’s Night, and they had it just as a cold open where it would just start like count off, “one, two, three, it’s been a Day’s Night…” And George Martin and I guess the other Beatles said, you know, we need an intro. And an intro could be, or typically was, a few notes that George would play, he would go home come up with some catchy possibilities. Here, he comes up with this pop chord that’s impossible to take apart. It doesn’t have a name. He knows what the notes are he’s playing because in a fascinating thing, which I never knew until you know, I really started studying. The song ends with just a guitar playing separate notes, what’s called an arpeggio, just different notes in an order. And it turns out that those notes that he plays separately at the end of the song collectively make up that chord that he began the song

BS: So it bookends the whole song. Oh, interesting.

SR: Yeah, that’s just genius of a whole other level. And these things, you know, they work, they don’t work, but when they do work, it’s often on a subconscious level. And maybe that goes back to when you asked me, what is the pleasure or the point of deconstructing how these songs get put together, because isn’t that fun to know? Oh my God, those trailing notes at the end are the same notes that make that opening chord? And you know, it’s just the way he conceived of music and its possibilities. And we haven’t even started speaking at all yet about his particular writing and his lyric writing too, which is a whole other topic we’ll get to. But it was, it’s those kinds of things. So in “A Hard Day’s Night” that, and he does other stuff in that song too. He plays an incredible solo, you know, instrumental piece in the middle of the song, down, down…

[MUSIC: Clip of guitar solo from “A Hard Day’s Night”]

You know, which is loosely based on the melody, but takes it to another place, but also is so perfect, and makes the song so much more interesting than if it was just singing the basic verse over and over again.

BS: Maybe you can talk a little bit about the process that you started talking about—assembling the song. So Lennon and McCartney would come in with, you know, in many cases, with the song, and they would present it to the others. Yeah. How would you describe how those things get put together? So they decided, collectively, in the case of Hard Day’s Night, yeah, we need something at the beginning, right? What about the other elements like that? The guitar solo, for lack of a better word, yeah, in the middle is that comes in just organically or from playing it over and over again, and figuring things out, you know? For someone who’s never written a song or been in a band, yeah, you know, how did that work for them?

SR: Well, for when we’re talking about a like a solo that George plays, he took that very seriously. He didn’t just improvise a solo. He didn’t just rattle off a blues improvisation, which, you know, if there are two kinds to really, to simplify this, there are two kinds of guitar solos, there are blues based solos, which basically there are blues scales, and it means that the guitar player, he knows what the chord changes are, and there are certain notes that you can play. You can play within each chord, and you put them together in your own unique way, but they’re basically determined by the blues progression. That’s what Eric Clapton does, for the most part, with a few exceptions, with a few amazing exceptions. At his very best, George does not do that. He does almost with maybe one or two exceptions, in his entire career with The Beatles and in his solo career, he very rarely just improvises on the blues, on the blues changes. There are very few Beatles songs, in George Harrison songs, that are even based in the blues.

Which is another very interesting thing about The Beatles, which separates them, say, from the Rolling Stones, who started out as a blues band, electric blues band based on Chicago blues. And that was the music they loved, and that was the music they were most influenced by. Not the case with The Beatles. They certainly knew about that music. But, you know, they present the song and it’s like, okay, George, these eight bars here, this is for you to fill with a solo. George would, for the most part, take that home with him and work overnight to compose a solo that he thought would enhance the song, and, you know, maybe even elevate it, in the sense of how it relates to the music, how it relates to the emotion of the song, the meaning of the song—two different things that may not sound like such a great big deal, but it is because so many people, the expectations are very often, or maybe even after that, that people will just like, be right there In the studio and come up with some really cool riff. And certainly, plenty of people do that. George actually got a bad rap from some people because of how slow he was. Slow meaning like, give me overnight. I’ll stay up all night. I’ll compose the perfect solo. Come back, and then they are perfect. It’s like, give the guy a break. He really cares. He wants to do the best possible thing he can do. He doesn’t just want to play a flurry of notes that you know would fit into the song. Would sound okay, but, but don’t do anything for it. This is why, to some extent, I consider George on many songs to have been a co-composer, because, yes, Lennon and or McCartney wrote the melody, wrote the lyrics, wrote the basic chord changes. But until you bring that to life with a band in the recording studio, you don’t have a Beatles song.

There are exceptions, obviously, like Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday,” which is basically a solo tune with a string quartet added after the fact, at the suggestion of George Martin. Brilliant idea, and it works. And “Yesterday” is one of their, you know, the greatest songs ever. That’s, in part, how it’s done. You know, what is the magic of how what George did that night on his own, to come up with those things? That’s pure speculation. Yeah, only George knows that. I don’t think either of his wives knew that. I don’t think his bandmates knew that he would just come in and, you know, you see this to some extent, if you watch that eight-hour documentary that Peter Jackson made based on the filming that Michael Lindsay-Hogg did in January, 1969, at this intense period of rehearsals, you see some of this playing out that way. You see some music being created right there in the moment. You basically see Paul McCartney stumbling upon the song, “Get Back,” as if it already existed, and all of a sudden he falls into it, and it’s pure magic.

BS: Yeah, so that’s the documentary which was called, “Get Back.”

SR: Yes.

BS: How did that change everybody’s understanding of how George Harrison worked with the rest of The Beatles?

SR: Well, it’s a great question, and I think different people will have different answers. I actually dealt with that to some extent in the book. To me, it disproved a lot of the mythology that had grown up around those three-and-a-half weeks that January where supposedly it was all rancor and disagreement and arguing. You know, anybody who’s ever spent any time around a rock band knows that there’s gonna be some rancor and disagreement and hurt feelings now and then. But what people did not know about that three-and-a-half weeks—and what we clearly see in the eight hours of Peter Jackson’s documentary—is the incredible joy that when they were clicking, when they were really playing together, that they shared almost psychic awareness of each other and where they were going with the music and how much fun they were having and how much they did like each other.

You know, there are portions where there are some tete a tetes, a very famous one, which was seen in part in the original movie, “Let It Be,” which is where all the footage that Peter Jackson used was filmed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg as part of what became the movie, “Let It Be.” So there is a very famous scene where Paul and George are sitting down, and Paul is trying to get George to play something a certain way, and George seems to be kind of miffed that Paul is telling him what to play. And he finally says, “Play what you want me to play. I won’t play if you don’t want me to play. Whatever it is that pleases you, I’ll do.” When you saw that in “Let It Be,” it was like, oh my God, these guys really did not like each other. But when you see it in the more expanded version, you actually see a very civil conversation. I gained much more empathy for Paul McCartney than I had before: I had seen that Paul was struggling because they didn’t have George Martin producing these sessions for whatever reasons. They were doing it on their own. There was no producer. Nobody was saying, let’s work on this song. Let’s, you know, focus here. It all kind of fell on Paul’s shoulders, simply because John Lennon was kind of out of it, both, maybe because of chemicals he was ingesting, because of other things going on in his life that he cared about more than The Beatles at the time, relationships, other projects. Ringo seems in rough shape. He comes in on most, most mornings you see him, he’s very his eyes are red rimmed. There’s even one morning where he says, somebody says, “How are you?” And he says, “Well, I’ll be honest, I’m not doing very well.” And what he means by that is he’s hungover.

And one morning, George comes in, the first Friday after they had kind of, you know, a working week, which was frustrating, because nobody really knew what they were doing. Are we making an album? Are we rehearsing new songs? Are we making a movie? Are we rehearsing for a concert? None of these questions were answered beforehand, so George comes in on the Friday morning, and he’s in a bad mood to begin with. This was another revelation, I think, of “Get Back,” which drew on much more of the footage than was seen in “Let It Be,” and that is that George arrives in the studio one morning in a really pissy mood. Something happened before he even got to the studio, and very famously, by the time lunch rolls around that Friday, George starts packing up his guitar, and he says to the guys, “Okay, I’m leaving now. I’m leaving the band.” And he gets up and walks out, and this was supposedly “George quit The Beatles.”

And for my extensive interviews with Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who was filming all this, and who was in the room the entire time, for the entire month, you know, as much as any of The Beatles were, he was there, you know, he said, yes, there was an undercurrent and a bubbling over of long-term resentment or hurt, but there was no triggering moment that made George really quit the band. In fact, he was having domestic problems, and he came in after a really bad night between himself and his wife, and another woman was involved, and that the previous night, he had been up all night reconciling with his wife. So the last thing he wanted to do was to go to this, you know, cold, cavernous film studio, which is where they began rehearsing, and sit around and just kind of twiddle his thumbs while they all tried to figure out what they were doing. He had something more important to be worried about that was to get home and to reconnect with his wife, Patty Harrison at the time, and right away, over the course of the weekend, The Beatles got together several times, including George, to try to work things out so he didn’t just quit the band and say, I’m out of here.

You know, he was frustrated. He left. Maybe he made it sound like he was quitting the band, but he turned right around and negotiated. He had some very valid complaints. What are we doing in this cavernous film studio where we’re making music and this place is not set up for that. We have our own recording studio in the basement of the Apple building—Apple being The Beatles’ company, you know, let’s just go there, where it’s more conducive to recording, to hanging out. It’s not, it’s just our place. We don’t have people coming and going all the time, which you see happening in the movie.

BS: When did that documentary come out?

SR: I think two years ago this fall.

BS: So you were deep into this yes project, yes?

SR: Yeah.

BS: So what was that like when you actually sat down to watch it?

SR: When I heard it was coming, yeah, I was so thrilled knowing that I would be able to, you know, knowing that everybody who wrote a book before, already written a book, didn’t have access to this stuff. I mean, there may have been a few people who did but, but the vast majority of the people would not and this was perfectly timed for me to write about it, and then to talk to Michael Lindsay-Hogg about just what it was we were seeing, what was going on, what didn’t we see.

BS: And is there anything that you had already written that you went back to change?

SR: Yeah, I don’t think at that point I had yet written about that. I just wasn’t up to that part yet and or that chapter, you know. I didn’t write the book from the beginning to the end as it reads. I wrote different pieces in different ways, and shuffled them around and, you know, you change things as you go along. So, yeah, but knowing that was coming, yeah, all right, I’m gonna watch this three or four times, this eight-hour documentary, yeah, and really study. And I sat there with a notebook, and like, you know, wrote down not just notes in general, but actual quotes. Then there was a beautiful, big coffee table book that they produced to go along with it, and I got that, which had a lot of the dialogue already there. So it was a great resource, perfectly timed for my schedule.

BS: Nice when those stars align like that!

SR: Yeah, they don’t—that doesn’t happen too often.

BS: So let’s go through a couple other songs that will bring us a little further through George Harrison’s life and some things that you wrote about. So you wrote about, “If I Needed Someone.”

SR: Yeah.

BS: And you pointed that that was not released as a single. It wasn’t even a B-side when it came out, and then it has become a signature Beatles tune.

SR: “If I Needed Someone” is such an incredible song—coming when and where it did and what it represented about George as a songwriter. So the song was on the album “Rubber Soul,” and George wrote it and sang it. So let’s take the music first. It’s what I referred to before as “jangle rock.” His guitar intro and riffs and licks are full of that echoey Rickenbacker 12-string jangle sound and the song itself, even though George wrote it, sounds totally like a Beatles song, but when you pay closer attention to it, some things about it really stand out. So you know the title is, “If I Needed Someone,” which is very—even from the title, that’s kind of different from the songs that The Beatles had previously done in the way that Lennon and McCartney wrote. And then what’s even more interesting is throughout the song, it’s in the conditional tense, if this, if that were to happen. Conditional slash subjunctive? I’m not really great on the terms of English grammar. I know how to write them. I don’t always know what they were, but there’s something in that category. And I don’t know what George knew if he was aware of what he was doing, but it was brilliant to write, in a sense, a love song, but all in the conditional tense, and as I write about in the book, he sings it in such a way that the phrasing of the lyrics conveys a musical meaning, the same as which lyrics convey meaning, and that is this sense of ambivalence.

[MUSIC: Clip from “If I Needed Someone”]

So he doesn’t sing where, typically where the beats would be. He sings off of them. So it’s a little bit of a distancing kind of strategy, narrative strategy, very sophisticated, like I say, how much was he aware of it? I’m thinking, how much was this just some kind of subconscious channeling of something? I don’t know, I don’t know, to quote George Harrison. And it turns out that this is a strategy he will use over and over and over again throughout his songwriting career. Which, you know, for his solo career lasts from 1970 until, really, up until he died in 2001. He died a month after 9/11.

BS: So you mentioned earlier about his introduction to Indian music, working with Ravi Shankar and his spiritual journey.

SR: Yeah.

BS: And one of the songs that you wrote about was “Love You To”, which I think you described it as the first one that really brought that out in their music. Is that accurate?

SR: Yes, there were hints of it before, most obviously on “Rubber Soul,” in the John Lennon song, “Norwegian Wood.” Lennon just basically had a guitar song, and he said to George, hey, why don’t you pick up that Indian guitar and play that on this? And what he was talking about was a sitar that George had recently bought and hadn’t even taken lessons on it yet. Was kind of like, picked it up, it has nineteen strings, and he was sort of like working backwards and trying to play it as if it was a guitar. And so what you hear on “Norwegian Wood” is you hear George Harrison playing sitar. So clearly sounds Indian, because it’s got that, you know, that kind of quality to it, even though he’s not playing the sitar properly. And as I note in the book, Ravi Shankar, who he will, later on, get to know and get to study with, kind of gave him props for actually having done a good job on “Norwegian Wood” with a sitar that, you know, he did what he could, and he made something of it.

But to get more into it, so he’s studying more. And the album after “Rubber Soul” is “Revolver.” And at this point, George has been studying with Ravi Shankar, with other Indian musicians in London. In particular, there’s an Asian music circle that he would jam with, or just attend and learn from those musicians. So that song, “Love You To,” on “Revolver,” the closest that George came up until that point to writing authentic Hindustani classical music played by the members of the music circle, as well as George, which was pretty revolutionary. There were other hints of Indian sonorities on the album, on “Revolver,” and there will be more to come on “Sgt. Pepper,” the song “Within You, Without You,” which gives my book its title, on “Sgt. Pepper,” is again totally based, structurally, sonically, instrumentally, on Hindustani classical music, which George fuses with rock music with his music.

The fusion of Western music and Indian music was just starting to happen around the same time with a few other people, famously Ravi Shankar and, oh, I just had the guy’s name, famous violinist. They had just made an album together, and even Ravi Shankar and his ensemble were stretching their music and making some of it a kind of East-West fusion. So all of these things are happening at the same time, the fact that The Beatles come out with these songs that eventually create the genre known as raga rock is just, you know, the biggest thing in the world, because The Beatles are the biggest thing in the world, and so it proves incredibly influential in so many ways.

[MUSIC: Clip of “Within You, Without You”]

It introduces the basic sounds of Indian music to Western audiences, to Beatles listeners. It, in particular, influences other musicians who are listening closely and are likewise finding ways of incorporating some of this. The Kinks did that. Ray Davies was really into that around the same time. Donovan did that. The Birds did some of that, and on and on and on.

BS: And what was the audience reaction to it when it first landed?

SR: Um, I think it was very positive, because this is all happening at the same time as what we call the counterculture, the 1960s counterculture, where Americans in particular are overthrowing stuff they’ve been handed down as truths and verities, and looking for other ways of thinking about the world, philosophizing, believing because, as I said earlier, and as is happening with these songs that George is playing, they’re very tied in with Indian spirituality.

George is also introducing those concepts in the songs, to say nothing of the sound of the music. There’s also an aspect of the psychedelic movement which is a polite way of talking about people dropping acid, taking LSD at the time becomes a big thing, and The Beatles had done that themselves earlier. And so you have all of these things kind of feeding off one another. But when The Beatles go to India and come back with starting to play Indian music and sing about Indian concepts, it just opens this incredible door. Yoga becomes a big deal. Meditation, and transcendental meditation in particular, becomes a huge big deal as it is until, until today. You know, The Beatles just happened to get hooked up with one of the main Indian gurus of Transcendental Meditation, the guy who’s patented that so that it’s uppercase T and uppercase M. You know, were there people who probably said, “What is this weird stuff?” Sure, I’m sure there were plenty. But I think, you know, the way it was—I mean, it’s not like The Beatles became an Indian band, but to have a couple of songs, or Indian sonorities here and there on songs, and often in ways that maybe people didn’t even realize—it was like, you know, a melody which is patterned along what’s called a raga, which is really just the way notes are organized in a melody line.

BS: And were there other contemporary bands at the time experimenting in the same ways?

SR: Like I said, The Kinks and The Birds in particular stand out. The Rolling Stones, you know, there were a couple of songs which I think they used a sitar on, and their song “Painted Black” is kind of in a, what we would call an Eastern mode, if not particularly Indian. Certainly they were, you know, experimenting. Their ears were tuned to what The Beatles were doing, just as The Beatles’ ears were tuned to what other people were doing.

BS: Now, let’s talk about a couple more songs and sort of move further along George Harrison’s career path. “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

SR: Yeah.

BS: So, describe that.

SR: Well, there’s a lot of interesting things about that song, a theme that runs throughout George’s songwriting is actually writing about music. So what’s a more immediate, direct metaphor for human emotion to a guitar player than the sound he gets out of his guitar? Hence, While My Guitar Gently Weeps, and what was what happened with that song is, as with many songs, you know, George would bring them to Lennon and McCarney, he would play them ironically, a song that eventually became very well known and considered one of the best Beatles songs for its electric guitar solos. And I’ll talk a little bit more about that in a second.

[MUSIC: Clip from “My Guitar Gently Weeps]

SR: It began as an acoustic guitar song—if you get, you know, they’ve had all these box sets in recent years which have all the outtakes and demo versions and an early version of, well, “My Guitar Gently Weeps.” It’s George playing, just strumming acoustic guitar chords and singing it. But rightly so when he brought it to the band, you know, and they talked about it and they start trying to put it together as a rock song, it was a difficult time. Because this comes during the making of what we call “The White Album.” “The White Album” is actually called “The Beatles.” That’s the name of the record. But because it was just a blank white LP sleeve, it became known as “The White Album.” So that’s what we’ll call it, just to make it easy.

That was a tough album to make because it was the first album where the band was not really, well, not the first. I guess “Sgt. Pepper” was the first. It was a continuation of what began with “Sgt. Pepper” in that all four people, members of The Beatles, are not in the studio at the same time, all playing together, capturing the sound live as a band, then following up with overdubs and re-dos and, you know, taking a portion from this take and putting in that take. But it had really devolved in “The White Album.” So that some people listen to the double album of “The White Album” and hear four different solo albums, really, that everybody had their own songs and then that it didn’t cohere. I’m not making that case. I’m just talking about the background of how this song was made.

So, George was frustrated with how a number of the songs he brought to the band for the sessions that would produce the White Album where the group was not particularly very enthusiastic about or, you know, everybody cared about their own songs and not anybody else’s. So George is driving with Eric Clapton during this time one evening, and he says, “Come to the studio with me. I want you to hear a song.” And he goes in and plays what they’ve been working on, “My Guitar Gently Weeps,” and the other Beatles are there. And he says to Eric, “Okay, when we get to this point, I want you to play a solo.” And he has Eric Clapton play a guitar solo on a Beatles song, which was unheard of, you know, like you may have had, like I say, you may have had a classical musician play strings or horns or something. Later on, you’ll get some other ringers in there. In particular, Billy Preston on the last couple albums, becomes a fifth Beatle.

So Clapton does come up with a really good solo, which he patterns very much along the lines of what George Harrison might have played. He doesn’t do his Eric Clapton thing, which is just blues licks. He actually does do a composed solo, which he very much tries to make in the style of what George would play. And even tells the engineers to, you know, whatever they are doing in terms of guitar tone, because Clapton is a very different tone when he plays a guitar than George Harrison. And that’s just a personal thing that different guitar players at that level have their own sound, which is a combination of just what guitar they’re playing, but really their touch and their feel. And Clapton was, you know, he knew that this was like a huge step. And in fact, for years, nobody even knew it was Eric Clapton. He didn’t get credited on the album for playing on that song. And it certainly sounds like it could be George playing. And interestingly enough, when the concert for Bangladesh comes around in 1971, if I’m not mistaken, in August ‘71 Clapton is on stage. They do that song, but Clapton, for whatever reason, is unable to play his solo. And George then just steps up and plays it and plays it perfectly, and it sounds just like what it sounds like on the record.

BS: So that’s interesting. So, 1971 is that when George Harrison’s first solo album came out, “All Things Must Pass.” When was that?

SR: It was probably fall, 1970. Because it certainly came out before Concert for Bangladesh, which was in the summer of ‘71.

BS: Okay, so let’s talk about that album, “All Things Must Pass.”

SR: Yes, yeah. Well, “All Things Must Pass” is arguably George’s greatest album, arguably the greatest single album by any of the members of The Beatles is a solo album, and arguably one of the greatest albums of all time, you know. And there’s so many different things going into this album. First of all, George has been compiling songs. He’s been writing songs since 1966, so now we’re in 1970 so it’s five, four or five years that he’s been sending up songs, some of which he presented to The Beatles and that they ultimately said no, including the title track—which in the movie “Get Back,” you see The Beatles learning the song and rehearsing it, and they actually do a great job at it. And they talked as if that was going to be in the set of the concert that hadn’t really yet been determined if it was going to happen or not. But even when they’re we’re still talking about when they finally decide to go up on the rooftop of the Apple building, they’re expecting George to do “All Things Must Pass.” He withdraws it. He says, “No, it wouldn’t fit,” and that was a smart thing for him to do, because it would not have worked on the rooftop the way all those rock songs they decided to play worked anyway. So he has this song, and he has a bunch of other songs, and he’s writing up a storm, and it’s his album. He doesn’t have to get the approval of Lennon and McCartney for whatever songs he wants to put on the album. So you know, the number of amazing songs on “All Things Must Pass” besides the title track or a song called “What is Life?”, a song called “Awaiting on You All,” “The Art of Dying.” In particular, there’s a cover of a brand new Bob Dylan song that he does called, “If Not For You,” which Dylan’s version comes out just about around the same time. But what’s really fascinating is the very first song you hear on “All Things Must Pass” is a co-write that George and Bob Dylan wrote this song together.

And I just think that was one of the rashest and funniest moves that George could make. So here it is, The Beatles break up. Everybody’s putting out solo albums, and the first song on his solo album is a co-write with Bob Dylan, who is the only other person creatively who is in the league of The Beatles in in rock music. So it’s as if to say to Lennon and McCartney, who needs you? I’ve got Bob Dylan. All things must pass. So he wrote this song before The Beatles broke up, and before it seemed like The Beatles were going to be breaking up. That title takes on entirely new meaning after the group has broken up and he’s putting out his first solo album. To call it “All Things Must Pass” sure cannot but help but be thought of as a commentary on The Beatles.

BS: So, “My Sweet Lord,” when, what year, roughly, did that come out?

SR: So that was on that album.

BS: Because I thought it was interesting—in reading what you wrote about that—that he had a lot of admiration for Smokey Robinson. And you noted in the book that when that song rose up the charts, it knocked “Tears of a Clown” from the number-one spot. And then it also had a bit of a complicated history.

SR: Well, first of all, “My Sweet Lord” was a huge global hit. It was number one everywhere in the world. It was the biggest Beatles solo hit up to that time, one of the biggest ever to this day, and it’s a fascinating song, because it’s basically a prayer. It’s basically almost like a mystical chant, “My sweet Lord, I really want to see you. I really want to be with you.” Mysticism, religious mysticism of any kind is about connecting directly with the Godhead, for lack of a better term, with divinity and all this song is talking about is wanting to have that experience.

[MUSIC: Clip from “My Sweet Lord”]

SR: Also, the chorus or the refrain, not that there’s necessarily a difference between the two, but the words that that he keeps coming back to in that song are in foreign languages, are not in English, which is all the more spectacular for an English slash American, primarily, artist to have a global hit with a song whose chorus is a combination of Sanskrit and Hebrew. And what I’m referring to is Hallelujah, Hare Krishna, which gets chanted over and over again throughout the song. Hallelujah is a Hebrew word which means praise God, obviously became part of the Christian liturgy, too, so that it’s often used in churches. And Hare Krishna Hare Rama are ways of praising the Lord in Sanskrit, and later in the song, he goes through a whole series naming a bunch of different Hindu gods. Very unusual for a pop hit, for a huge pop hit, to have a chorus in Sanskrit and Hebrew.

[MUSIC: Clip from “My Sweet Lord”]

SR: You know, it also it introduces the world basically to solo George Harrison, it’s got that slide guitar sound for the for the first time. You know, George really only picked up the slide guitar at the very end, or even after The Beatles broke up. He was turned on to it. He loved the way it sounded. He played it in a way that nobody else plays it, that you know you could instantly differentiate George Harrison’s slide guitar from any other number of slide guitar players. It’s just, again, his touch, his musicality, the way he played it that very distinct hook which is so identifiable, down, down, down, played on a slide guitar.

Now what happens is, there is this song from back in the early 1960’s called “He’s So Fine,” which was recorded by a group called The Chiffons. And some people thought they heard a resemblance between “My Sweet Lord” and “He’s So Fine.” “My Sweet Lord” opens up with George’s slide guitar playing that riff that I just kind of tried to sing. “He’s So Fine” opens up with, immediately, with female vocals that go, “doo-lang doo-lang doo-lang, he’s so fine, wish you were mine.”

[MUSIC: Clip from “He’s So Fine”]

SR: Like, you’re talking the difference between that and “My sweet lord, oh my lord. I really want to see you. Really want to be with you.” So lyrically, conceptually, mood-wise and musically, the songs bear almost no resemblance at all, “My Sweet Lord” and “He’s So Fine.” Yes, those are the same notes—that is the beginning and end of it. There was nothing else in the Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine” and George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” which match up. “My Sweet Lord” has different other musical sections to it, whereas “He’s So Fine” just continues in that basic thing. It’s like a two-minute early ‘60s pop-hit girl-group song.

Nevertheless, the publishers of the original “He’s So Fine” sue George Harrison for plagiarism. So basically, after years of legal maneuvering and after years of working with his then manager, Allen Klein, who became the manager of John Lennon, Ringo Starr and George Harrison, just around the time that The Beatles were splitting up. In fact, that was part of the reason they did split up, because Paul McCartney could not countenance being managed by Allen Klein—for good reason, as it turned out, and he was actually warned against it. And in the movie, “Get Back,” John Lennon, like, tells the engineer who had worked with the Rolling Stones—who Allen Klein had managed—he says, “Oh, I met this guy, Allen Klein. He’s great. We might hire him to be our manager.” And the engineer says, “Oh, be careful there,” because he had seen what the Rolling Stones had gone through with Allen Klein, and it was ugly. So Allen Klein, who’s representing George Harrison in this lawsuit, defending him and trying to get him out of it, even to the point of suggesting that George just buy the publishing [rights] for that song. So there’s a payoff of something under $200,000, which was market rate at the time. And then it would be his song, and there would be, you know, they would get their share of something.

Anyway, that that doesn’t happen. Negotiations go back and forth. At some point, George is dissatisfied with how Allen Klein is handling the situation. George fires Allen Klein as his lawyer slash manager, and Klein turns around and he buys—he personally buys—the rights to the song “He’s So Fine” so that now he has switched sides, which is totally unethical for a lawyer to do. My wife is a lawyer, and she’s told me that this is actually taught in law schools, because it is an egregious kind of example of what you can’t do as a lawyer. So anyway, it becomes this legal battle that goes on and on and on eventually gets settled, but not without cost, some damage to George’s reputation, to Georgia sanity. This is all on top of lawsuits which are flying back and forth throughout the 1970s among, and in-between, The Beatles themselves to, you know, break their contract, to try to figure out how things are going to work now moving forward. Because, you know, to this very day, there’s still Beatles, Inc. You can’t just, you know, the band can break up, but the business lives on and on as this, because it’s, I mean, it’s a perennial moneymaker.

So the best thing to come out of it, you know, George talked about how, for a year or more, he couldn’t—he was afraid, whenever he wrote something, that it might be, he may have, like, heard something and based it on that. He couldn’t listen to songs without hearing, not just his own, but other songs, without thinking he was hearing other songs. That really did a number on him. And he wrote about this in a few songs in particular, the best, like, I say, the best thing to come out of it was he did this great song in, I think, about 1976 called “This Song,” which is, totally tells the story. “It’s this song. Don’t infringe on anyone’s copyright. This song, my expert tells me it’s okay.” It’s a very funny, sarcastic, witty take on that whole experience. And this was right at the time that music videos were starting to be made for MTV. Is a very funny music video which the guys from Monty Python helped him make as he became very good friends with them. So “My Sweet Lord” has that incredible backstory to it, besides just being one of the greatest songs.

BS: So let’s wrap up with—well, first let me point out that there’s much more in the book, his work with Traveling Wilburys. You talk about other songs like “I Got My Mind Set On You,” which is one that I remember very clearly, it was at a formative time for me when that song became a huge hit.

[MUSIC: Clip from “I Got My Mind Set on You”]

BS: There’s more about Dylan and Clapton in the book, and you touch on also this idea of his emotional state, whether he suffered from depression. Given how deeply enmeshed in all of this work, of George Harrison’s work, for so long—and you write, I think, in the introduction that you spent a couple of years in the writing phase of this—was there anything during the writing part of this book, and any of things that you discovered by looking so deeply at each of these songs, anything that surprised you?

SR: That’s a great question. I hadn’t—you know until I had really sat down with it all, that idea that George Harrison, through on the evidence of his songs and how so many songs have images of clouds and sadness, I knew that George was an introvert. I knew that he was shy, although he also was very witty and could be very assertive if he wanted to. I hadn’t realized that he may actually have been clinically depressed, and there’s no way that I know that he was. There’s no way that we know that anybody really is. I mean, you know, this is—it’s just a new term we use, or new, as in the last, I don’t know, 50 or 100 years, but there’s an awful lot of songs that would suggest that he had somewhat of a depressive outlook, which I wouldn’t say is a total surprise. I just hadn’t realized how much of it was in the music itself.

BS: And if you were giving advice to someone who wanted to dive into George Harrison’s music the way you did, what will be a good entry point?

SR: Wow.

BS: After reading your book, of course.

SR: Yes. Well, that’s a great, terrific question, and it’s so hard because, you know, there’s The Beatles and there’s his solo career. So I’m tempted to say, “All Things Must Pass,” really.

BS: And that’s his first solo album.

SR: Although, you know, part of me says, well, maybe you should listen to Abbey Road, the final Beatles album, because the two big hits off that album, “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun,” although they’re Beatles hits, those are George Harrison songs. He wrote them, he sings them. And those are the two songs, if you go on Spotify or streaming services where they tell you how many streams there’s been, perennially, “Here Comes the Sun” and “Something” are the number one and number two songs—Beatles songs—that get streamed.

So by the end of The Beatles, he becomes the hit maker, which is, again, just another—there’s, I think you probably picked up that there’s a lot of ironies running throughout George’s life and career, both good and bad. So I guess “All Things Must Pass” is as good a place to start as any. And then go back to “Revolver” in particular, which I just think is the best Beatles album, and it has three great George Harrison songs on it, which is unusual for the time, usually had one or two.

BS: Well, Seth, thanks for this conversation. It’s been a lot of fun, really interesting.

SR: Bill, thank you so much.

BS: And congrats on the book. I really enjoyed reading the book, and I had a browser open and clicking on YouTube videos to listen to songs. It was great.

SR: That’s great.

BS: That was rock critic Seth Rogovoy speaking about his new book “Within You, Without You: Listening to George Harrison,” published this month by Oxford University Press. To learn more, visit sethrogovoy.com. And for more podcast conversations and exclusive, in-depth reporting about the Berkshires and beyond, head to berkshireargus.com. I’m Bill Shein, and thanks for listening to the Berkshire Argus podcast.

∎ ∎ ∎