I.

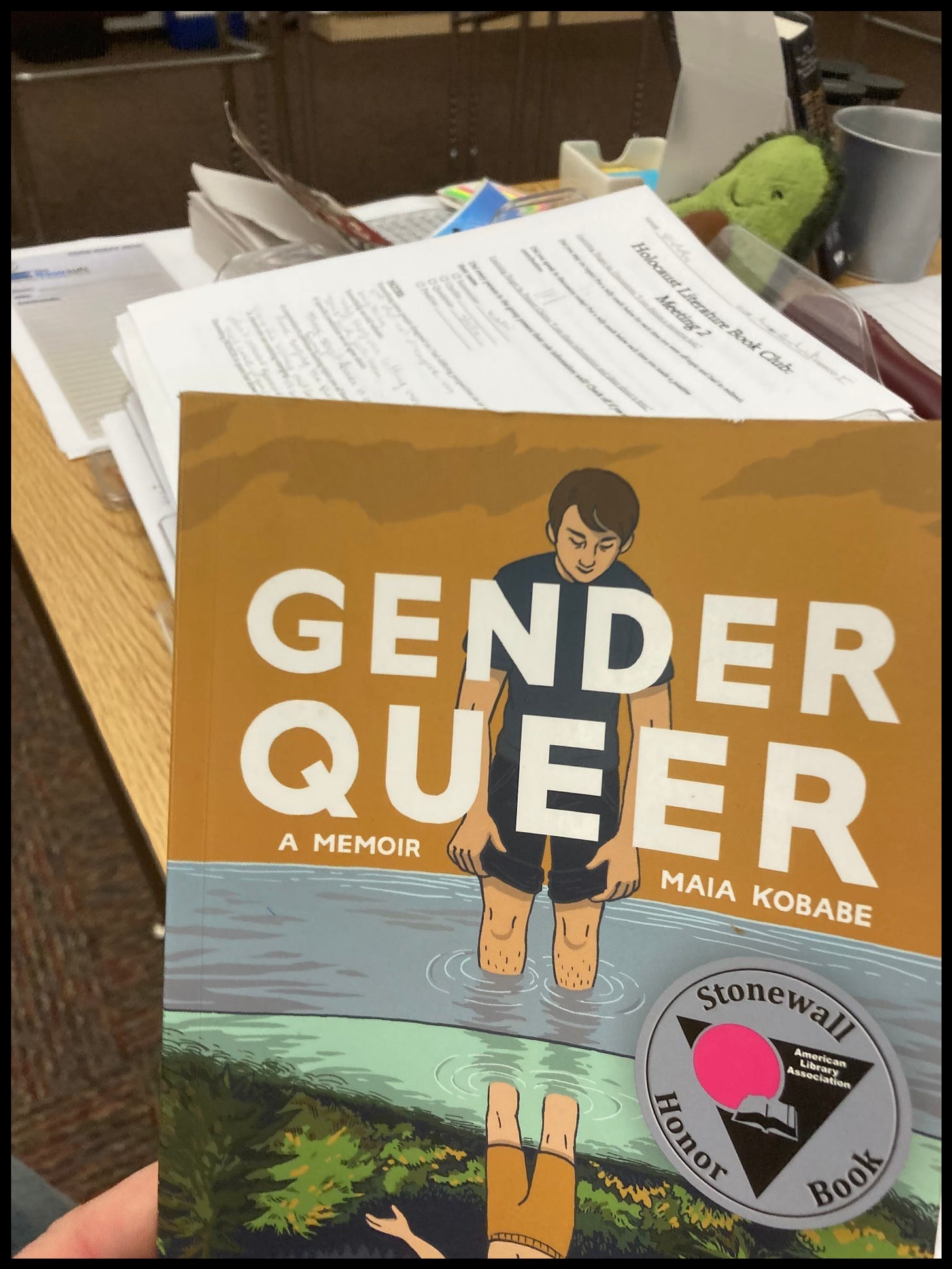

In the final pages of Maia Kobabe’s “Gender Queer,” a 2019 comic-style illustrated memoir of eir confusion around gender identity and sexual orientation, Kobabe, who uses e/em/eir pronouns, grapples with a question: Whether to tell eir students in a comics-drawing workshop that e is nonbinary and asexual.

“The kids I teach are primarily A.F.A.B. [assigned female at birth] and they range in age from 11 to 14,” reads the text above one page of drawings. “Those were my first big years of gender confusion, but I doubt anyone would have guessed just by LOOKING AT ME.”

Underneath those words are drawings of Kobabe in sixth through ninth grades, with long hair and an appearance that e suggests would lead most to assume a female gender identity. “I wonder if any of these kids are trans or nonbinary, but don’t have words for it yet?” e ponders while teaching the class.

As the book concludes, drawings show Kobabe tidying an empty classroom while more thought bubbles continue the thread. “How many of them have never seen a nonbinary adult?” e asks in one frame. “Is my silence actually a disservice to all of them?”

More thoughts about coming out to eir students reflect both personal history and professional fears. “Having a nonbinary or trans teacher in junior high would have meant the world to me,” e writes, but then wonders about repercussions: “Could a parent complain and get me fired?”

II.

Last year, the twentieth of November fell on a cool, autumn Monday. As the sun set, temperatures slipped toward freezing and a light wind kicked up fallen leaves. Still too early for snow, a cold rain would fall the following evening.

Across southern Berkshire County, holiday-season excitement merged with local buzz about the imminent release of “Maestro,” the Leonard Bernstein biopic that chronicles the conductor’s career, his complex marriage to the actor Felicia Montealegre, and his intimate relationships with both men and women. (It was filmed in part at Tanglewood, in Lenox.)

In Great Barrington, youth-basketball leagues were a few weeks into the season. Local and traveling teams of third-to-eighth graders practiced most nights at the Housatonic Community Center, known as the Housy Dome, and in the gymnasiums at Muddy Brook Elementary and W.E.B. Du Bois Regional Middle School, both located off Route 7 near the town’s northern border.

“When we’re not educating three hundred and fifty kids, we try to make the building available to a variety of different programs,” Miles Wheat, who became the Du Bois principal last year after seven years as assistant principal, told me during an interview in his office last month. That includes education-related after-school activities and community events like sports, adult English instruction, and yoga classes.

Most afternoons at Du Bois, a program for students called Community Learning & Enrichment Opportunities (CLEO) runs until the late bus pick-up at 5:15 p.m. But on this particular Monday, there was no CLEO programming, according to a posted schedule.

Still, there would be people and activity at Du Bois through the late afternoon and into the evening. Two basketball teams would practice in the school gym: Tom’s Toys Bantam, a dozen third- and fourth-grade boys and girls from 5:30 p.m. to 7:00 p.m., and Wheeler & Taylor Senior, ten kids from seventh and eighth grade whose sneakers squeaked across the hardwood until 8:30 p.m., according to the league’s online schedule.

Modern school-security realities mean that access to Du Bois and other Berkshire Hills Regional School District (BHRSD) buildings is tightly controlled during the school day. But once classes are over, after-school activities and events require opening some doors for public access. “On any given day after school, is it possible to show up and find the door unlocked? Yeah, it’s possible,” Wheat told me.

That evening, as free throws and layups were hitting backboard, rim, and net, someone was walking the hallways of the Du Bois school. At around 7:45 p.m. they entered an English-teacher’s classroom—one that also serves as the gathering place for the Gender and Sexuality Alliance (GSA), an affinity club for seventh and eighth graders. It meets weekly for a 42-minute, combined-lunch-and-recess period that’s built around student-led activities and conversations.

“There’s a wide range of people who have a found a place there,” Wheat explained. The club typically includes around fifteen to twenty students. “It’s for anybody who is in the queer community, questioning their own gender or sexuality, and wants an explicitly welcoming, nonjudgemental place to spend lunch and recess for a day a week.”

It’s unclear whether the classroom door was open that night or a key was needed for entry. Inside, written in large letters on a wall-mounted whiteboard were the words “Making Connections.” Completed worksheets for “Holocaust Literature Book Club: Meeting 2” sat in a half-foot-tall pile on a desk. A small bookcase against one wall contained books for GSA that require teacher approval—and sign-out—for student use. And according to what this person later told police, on the teacher’s desk was a copy of “Gender Queer.”

Was what happened next an impulsive, spur-of-the-moment decision by someone who had reason to be inside a school classroom after hours? A good-faith-if-improperly-advanced concern about a controversial book? Or, as some in the community believe, the first step in a calculated plot to target a queer-identifying English teacher—one who has taught at Du Bois for more than six years and has been, according to parents and school administrators, a trusted advisor to students for whom GSA is a vital part of their middle-school experience?

(At the request of the teacher’s attorney, The Argus has agreed not to publish her name in our reporting at this time.)

Whatever the motivation, this person picked up the book and snapped at least three photographs: Two of the front cover and one of illustrations on page 167. That’s a page that since at least 2021 has been featured in social-media posts, deployed in media campaigns against politicians, librarians, and educators, and shown in viral videos of angry parents at school-board and town-government meetings across the country. The dialogue on that page was even read aloud by Sen. John Kennedy, a Louisiana Republican, at a U.S. Senate hearing last summer.

At that point in Kobabe’s memoir, e is 25 years old and has been dating a female-identifying partner, named only “Z,” for two months—and with whom e had eir first sexual experiences. Two illustrations on the photographed page show Kobabe and Z simulating oral sex with a sex toy while the text describes Kobabe’s confusion, discomfort, and disappointment. “Let’s try something else,” e says quickly. “Of course,” answers Z as they embrace. Following those words is a drawing of a heart.

In response to Kennedy’s criticism, Kobabe described that scene as one about consent. “That’s important to share, and it’s not one that I heard often when I was a teenager,” e told The Hill newspaper.

On the next page, Kobabe describes having little interest in sex—something that has confounded em throughout eir life and is explored throughout “Gender Queer.” At various stages of adolescence, e considers how to understand—much less describe—a mixture of uncertain and evolving feelings. “Now that I had sex a few times, I’m not sure I really need any more,” e writes after the encounter on page 167. For several more pages, Kobabe considers that question and decides that dating, at least for the moment, “is making me more and more confused and less and less happy.” She breaks up with Z.

The first edition of “Gender Queer” is 240 pages long. It’s a deeply personal exploration of issues related to adolescence, gender, relationships, and sexuality. A handful of pages feature sexually explicit drawings. In this fraught political moment, claims of “obscenity” and “pornography” have led to campaigns to ban the book—with teachers and librarians routinely accused of being perverts, pedophiles, “groomers,” and worse. That’s unfolded even as educators and library professionals say the story and its presentation represent an important queer narrative for those trying to understand gender identity. (The book is often at the top of “most challenged“ book lists.)

As a literary resource in schools, it’s excluded from Massachusetts laws on obscenity. But that’s not tamped down what some parents argue are reasonable concerns about whether seventh- and eighth-grade students should have access to it in school—not because of the subject matter, they insist, but because of the explicit illustrations. Others say the process for accessing it, which includes adult involvement, is appropriate and sufficient. And advocates say that complaints from a few outspoken parents shouldn’t narrow access to these books for others’ children.

As for age-appropriateness—a nuanced question when considering the developmental stage of individual preteens and early teens—it’s a book that the American Library Association awarded a 2020 Alex Award, “for books written for adults that have special appeal to young adults ages 12 through 18.”

At the virtual Alex Awards ceremony in June, 2020, Kobabe recalled that in the weeks after publication, she received daily emails “mostly from nonbinary teenagers, or queer teenagers, questioning people, parents with kids who had come out recently.” E called it “an outpouring of online love.”

But the person who took the photographs in the Du Bois classroom that night, and who would later make other allegations about the English teacher, was not a fan. And that’s why they were in the teacher’s classroom that night.

The photos themselves revealed when they were taken: Last month, through a public-records request, The Argus acquired copies of the three digital-photo files the complainant provided to police. One of them still contained embedded metadata including camera make and model, lens settings, and the date and time the image was captured. It revealed the photo was taken on Monday, November 20, at 7:47pm, with a second-generation iPhone SE, a version of Apple’s entry-level smartphone that went on sale in April, 2020. That embedded information is known as “exchangeable image file (EXIF) data,” and it can drop off when photos are shared in certain ways. It can also be modified or removed with software tools.

For now, at least, the person who took the photos remains known only to the Great Barrington Police Department, which has described the person as “a member of the school community.” That presumably includes a universe of parents, students, teachers, and staff—though evening access to a classroom, if the EXIF data is correct, may narrow the possibilities. The person is likely male, based on one use of the word “he” in a police report.

After the person took the photos on November 20, nothing happened for two-and-a-half weeks.

III.

Early on the afternoon of Friday, December 8, someone entered the Great Barrington Police Department—a squat former telephone-company office located on a roundabout near downtown. This person told Officer Joseph O’Brien that they had information to share but asked that their name be kept confidential “for fear of retaliation.”

With that promise from police, the person made three allegations about the eighth-grade English teacher in whose classroom the photos of “Gender Queer” were taken.

In order of seriousness: First, that the person “observed a student sitting on the teacher’s lap” and was “concerned about this conduct.” If true, it would represent, at minimum, inappropriate physical contact between a teacher and student.

Second, that he overheard the teacher “and a few other staff meeting with students in private and discussing subjects related to LGBTQ material and telling them not to tell their parents about it,” according to O’Brien’s written report [PDF]—a supplement to the main police report [PDF] and one that includes some details that have not been widely reported.

The main police report describes this claim a little differently, creating more confusion about context: “This person also reported to overhearing the same teacher telling students to ‘not tell their parents’ and that they observed a student sitting on the lap of the same teacher,” it reads.

And third—as local and national media outlets have reported since mid-December—the complainant “was concerned about images in a book they saw in the 8th grade English classroom,” as O’Brien summarized the conversation. (Based on police-report narratives and Argus interviews, the person who took the photos is widely assumed to be the same person who went to police, but The Argus could not independently confirm the connection.)

GBPD Book Search Police Reports

After completing the interview, O’Brien took immediate action “based on the three photographs and the reported conduct of students sitting on a teachers [sic] lap,” according to his written report.

That’s why he notified his chain-of-command. “Party in station to report suspicious activity,” a police log noted. “654 advised as well.”

That number, 654, is department code for the chief of police.

IV.

Paul Storti has been a police officer since 1989. He began his career with part-time work for the towns of Sheffield and Egremont before he joined Great Barrington’s department full-time in 1995. Stocky and affable, he was elevated to chief in December, 2020, with plans to increase community engagement and expand the department’s ability to respond to calls that might benefit from a mental-health co-responder—something he advanced during ten years as a sergeant under the former longtime chief, William Walsh. It’s an approach that has recently been at the center of the national discussion about policing.

Born and raised in Housatonic, Storti, 56, lives with his family in Great Barrington. He attended local public schools in the Berkshire Hills district and was a stand-out forward on the Monument Mountain High School boys’ soccer team. Storti’s four children range in age from twelve to thirty; they also attended local schools. Paige Storti, his twenty-six-year-old daughter, is a filmmaker whose documentary short, “The Backpack,” profiles her father and explores the emotional scars left by decades of police work in a small town. “I pretty much can’t go anywhere in the community without seeing something that reminds me of a tragic incident,” he says in the film’s trailer.

On that Friday afternoon in early December, Storti was at home enjoying a half-day off from overseeing the department and its roster of full-time officers. (The department employs nineteen officers when at full complement, but currently has only fourteen.) It was a little before 2:00 p.m. and he had just finished lunch. “I sat on the couch to relax for a few minutes and that’s when Joe [O’Brien] called me,” he told me last month. Storti left home immediately and headed to the station; he was there in five minutes.

After a briefing by O’Brien, the chief called the Berkshire Hills superintendent, Peter Dillon, at his Stockbridge office. (The school district includes the towns of Great Barrington, Stockbridge, and West Stockbridge.) He told Dillon about all three allegations made by the complainant—not just the concerns about a book. “I relayed that information to the superintendent when I initially spoke to him,” Storti told me. “It wasn’t just about the illustration. It was about those three points specifically.”

During one of our recent conversations, Storti explained how the department evaluates information provided to police. He described a two-pronged test that examines “veracity and credibility.” He said a witness earns credibility by identifying themselves to police. “They’re putting themselves out there, so you get automatic credibility by being named,” he said, as compared to an anonymous tip or complaint. “The other part is basis of knowledge: How do you know what you know?” In this case, Storti said, “It wasn’t second- or third-hand information that was being provided. This was firsthand information that they were reporting. So that’s what we look for.”

“Once we have a complaint, our goal is to verify and put some substance to it, and to get a better understanding of what took place. And that’s what we were doing.”

—Great Barrington Police Chief Paul Storti

The two allegations about the teacher’s interactions with students lacked key details like date, time, and others involved. Were they wholly fabricated allegations and age-old homophobic tropes used to target a queer teacher who works with LGBTQIA+ youth? At a late January meeting of a School Committee policy subcommittee, those allegations were described as “red herrings” specifically used to “activate” police involvement in the book complaint.

But on the afternoon of December 8, at least, Storti and his officers had a three-part complaint—made by a witness who came to the station and identified themselves to police—and long-established department policies that laid out how to respond. “We’re required to do a preliminary investigation,” Storti explained. “The importance of [a preliminary investigation] is to verify the information provided by the complainant to determine if it’s credible or not,” he said, reading from the policy. That includes speaking to witnesses and preserving evidence. “Once we have a complaint, our goal is to verify and put some substance to it, and to get a better understanding of what took place. And that’s what we were doing.”

While the other two allegations were more serious than a book complaint—and would both be quickly discounted after a conversation with school officials—the police department’s determined search for a single copy of “Gender Queer” established a narrative. But it’s one that’s been missing the key details and complexities that help explain why police were so adamant about going to the school that afternoon and why school-district officials signed off so quickly.

V.

Peter Dillon was hired as Berkshire Hills Regional School District’s superintendent in 2009 and moved with his family from New York City, where he’d spent fifteen years deeply involved in education-related work. He taught at large urban high schools in Brooklyn and the Bronx and served as principal of East Harlem’s Heritage School, which uses the arts to engage students and propel them to academic success. Later, he worked in the administration of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg and helped establish more than 150 new, small high schools across the city in just three years.

Those new schools combined smaller classes with what Dillon describes as “deep connections and relationships” fostered by advisory programs that connect educators with students in ways that are now common in the Berkshire Hills district. “Kids can really be set up to succeed, and again and again, we demonstrated that,” he told me during an interview last month. Those 150 schools graduated north of ninety percent of their students, he said, compared to the most challenged New York City schools that graduated fewer than half.

Experienced, level-headed, and seemingly unflappable, Dillon also has a pile of advanced degrees that includes a doctorate in curriculum and teaching; his 1999 dissertation examined teacher collaboration at New York City’s International High School, in Queens, which served recent immigrants from sixty countries who spoke forty languages. At some point, he also found time to serve as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, a collection of atolls and islands scattered across the central Pacific Ocean.

Over the last 15 years, Dillon has guided his rural school district through myriad challenges: From budget battles, to assorted merger discussions, to the controversial elimination of academic tracks in high school—known as “deleveling”—to a contentious and ultimately unsuccessful effort to convince Great Barrington voters to help pay for a new high school. (Monument was built in 1968, and few dispute that it is dark, crumbling, and insufficient for today’s educational needs. A new effort to design, fund, and build a replacement is underway.)

After living for eleven years in Great Barrington, he moved to Stockbridge four years ago. His three children all attended district schools; two graduated from Monument.

Over the last few challenging years, he helped guide faculty, staff, parents, and students through the sudden twists and unknown turns of the pandemic. Today he’s preparing the district for new changes and opportunities that include a growing number of immigrant families settling in the Berkshires. With the help of community members, the district is busy developing something called “Portrait of a Graduate,” a new framework and vision statement that will guide “what we want students to know and be able to do,” Dillon explained.

When he picked up the phone on the afternoon of December 8, though, a new and pressing challenge moved front and center. He listened as the chief of police described allegations about a teacher and a book that would typically come through existing school-district channels. The police wanted to immediately send an officer to Du Bois to conduct a preliminary investigation, Storti told Dillon. And they wanted to find the book. “By going directly to the police, they circumvented our process and caused all sorts of problems,” Dillon would tell me later about the unknown complainant.

He hung up the phone and immediately called Steve Bannon, the longtime chair of the BHRSD School Committee who joined that ten-member board more than a quarter-century ago, in 1997. For the last six years, Bannon, who works as a pharmacist at Fairview Hospital in Great Barrington, has also been chair of that town’s Select Board—the elected five-member municipal-government body that, through its hired town manager, is responsible for overseeing the police department. (Bannon was first elected to the Select Board in 2010.)

“By going directly to the police, they circumvented our process and caused all sorts of problems.”

—Peter Dillon, Berkshire Hills Regional School District superintendent

After talking it over with Bannon, Dillon called Wheat, the Du Bois principal, and then called Storti back and okayed the police visit. As Wheat waited for O’Brien to arrive, he recognized that it wasn’t his decision. “[Dillon] told me we were going to play ball with the police, who were going to try to show up in a non-disruptive way, in plain clothes, after the close of school,” he told me. “The superintendent said that it was their intention to search for the book.”

As made clear over the last two months in media reports, public forums, press releases, and apologies issued by Dillon, Bannon, and Storti, this was the moment of decision when things might have unfolded differently. At minimum, Dillon concedes, he should have reached out to the district’s law firm before acceding to Storti’s request. And, he told me, also ensure that the English teacher was provided an opportunity to have union representation or legal counsel present.

With the benefit of hindsight, Dillon has also said he should have seen more clearly the possibility, at least, that the three allegations might have been carefully constructed to target a teacher. At the January 11 School Committee meeting where parents lambasted Dillon, the School Committee, and police, he apologized again and described the complaint as a “racist and homophobic attack” against both the teacher and students in the GSA.

When I asked Dillon why his initial communication to parents about the book search—an e-mail on December 14, hours before the first news story would appear—didn’t mention the other allegations, he said it was, in part, related to “taking seriously” the confidentiality of personnel matters. “More recently,” he told me, “I’ve come to believe that whoever made this complaint didn’t have positive intentions. And what’s the point of reiterating what’s likely a false allegation that was used to open the door to attack somebody?”

How district and Great Barrington officials navigated that reasonable concern was almost certainly a factor in the narrative that emerged in the days and weeks that followed. Indeed, Dillon has since become more specific and forthcoming about the impact of those allegations as he collaborates with the School Committee to revise district policies related to the police. In a January 24 meeting of the district’s policy subcommittee, he noted several times how they complicated his decision-making on December 8. “Were the [other] two parts of the complaint crafted to encourage me to respond the way I did?” he mused. “It’s sort of obvious now that was the case, but in the five minutes that I was on the phone, it wasn’t so obvious.”

“What’s the point of reiterating what’s likely a false allegation that was used to open the door to attack somebody?”

—BHRSD Superintendent Peter Dillon

Dillon told me that policy changes will aim to clarify when a police response to schools is warranted. “One of the things we’re going to do is more clearly articulate the difference between something that’s an emergency or an imminent threat and something that can proceed on a different timeline,” he said. The allegations made alongside the book complaint highlight the complex policy challenge. “The thing that continues to be hard to parse out are the gray areas in-between, and if somebody is engaging in a process in a way that that’s inauthentic,” he said. “How do we protect ourselves against that?”

VI.

There may have been a Ghost of District-History Past hovering over the decisions made in those minutes after Storti’s first phone call, as Dillon and Bannon conferred about the information relayed by the police chief.

In 2017, Berkshire Hills settled a $4.5 million federal lawsuit brought by three former female students at the Stockbridge Plain School, one of the district’s elementary schools prior to consolidation at Muddy Brook Elementary. The suit alleged that from 2003 to 2006, when the students were aged eight to ten, they were sexually abused by a school counselor in his basement office and said the district was negligent because it didn’t prevent the abuse—or, once alerted, stop it from continuing.

Whether by coincidence or malicious design, the language used by the person who went to police on December 8 echoed some of the behavior alleged by those Stockbridge Plain School students years earlier.

According to the lawsuit, the counselor, whose job was “student support center coordinator,” regularly had students in his office during and after lunchtime and sometimes pulled them out of class. Alone with them in his office, he would sit them on his lap while they played games on his computer. The former students alleged that’s when he fondled them, sometimes penetrated them digitally, breathed heavily in their ears, and told them “not to tell anyone.”

The lawsuit was settled for an undisclosed sum and a release from future liability. (Dillon, who was not employed by the district at the time of the alleged abuse or the district’s response, has long declined to comment on the settlement.)

The troubling story unfolded over a decade-and-a-half; one 2017 news report said it was “haunting the district.” It began in 2004, when parents of three students repeatedly raised concerns with school officials about inappropriate touching by the school counselor, who sometimes rubbed the girls’ legs and buttocks while giving them piggy-back rides. The principal eventually referred the allegations to the state’s Department of Social Services (DSS), now called the Department of Children and Families, which, along with the Massachusetts State Police, investigated. The school district also conducted an internal investigation.

No referral for prosecution was made; investigators would later say it came down to “he said, she said.” But school officials said they instructed the counselor not to have any physical contact with students or put them on his lap. (The counselor continued to work for the district until 2007.)

When additional students, now teenagers, came forward in 2012, a state-police unit in the Berkshire County District Attorney’s office re-examined the case. This time, the former school employee was indicted on 19 charges including child rape and indecent assault and battery on a child.

In a dramatic 2014 trial in Berkshire Superior Court that included emotional testimony from alleged victims as well as questioning of the counselor, he was acquitted of all charges. In his testimony, he denied any inappropriate touching but conceded that even after being instructed not to have physical contact with students, he continued to sit them on his lap. “Generally, I was just trying to comfort them,” he testified.

“Were the [other] two parts of the complaint crafted to encourage me to respond the way I did? It’s sort of obvious now that was the case, but in the five minutes that I was on the phone, it wasn’t so obvious.”

—BHRSD Superintendent Peter Dillon

In 2012, after the counselor was arrested, Bannon wrote a letter to the Berkshire Eagle on behalf of the School Committee, which he took over as chair in November, 1999. He defended decisions made by school and district officials in response to the complaints and highlighted that the 2004 investigations found “there was not sufficient evidence” to support a finding of abuse or neglect.

“With this decision from DSS, and upon advice from legal counsel, standard precautionary measures were maintained. No additional or subsequent complaints against this employee were made to the district,” Bannon wrote. “While the current arrest and investigation may cause a retrospective review of actions taken, we remain confident that all parties, including the state agencies, took the necessary and mandated steps at that time to investigate the reported incidents.”

In both the 2014 trial and 2016 lawsuit, it was alleged that inappropriate touching and abuse continued despite any measures taken by school officials.

VII.

Miles Wheat, the Du Bois principal, lives in Housatonic. He joined the school administration as assistant principal in 2016 after working as a science teacher and assistant principal at the Berkshire Arts and Technology (BART) charter public school in Adams, Massachusetts. He had first visited Du Bois as part of a budding partnership between the schools, he told me, that included an exploration of ways to deploy “restorative practices.” That’s an approach to addressing school and student issues that, many believe, is more constructive and effective than traditional disciplinary tools like suspension. It aims to repair harm and restore relationships through the use of thoughtful processes and discussion; today it’s baked into the educational life of Berkshire Hills schools.

Wheat and his wife were considering a move to south county, so the opportunity at Du Bois meshed nicely with their plans.

You don’t have to talk to Wheat for long to see the affection he has for Du Bois students. “We have a pretty remarkable group of kids,” he said. “They are a group of very engaging and curious people.” He described the affirmative ways Du Bois aims to “build [school] culture” and engage students in that community-wide effort. “At this age, students are developing their personalities,” he explained. “And what we see all the time is that they’ll try things out: Do I want to be this kind of person? Do I want to be that kind of person? And some thoughtful guidance on ‘who do you want to be in this culture we’re trying to build’ goes a long way.”

“We have a pretty remarkable group of kids. They are a group of very engaging and curious people.”

—Du Bois Principal Miles Wheat

A lot of that is embodied in “crew,” an enhanced version of daily homeroom that Wheat said includes a focus on the development of social-emotional skills. That became a priority during and since the height of the pandemic. It includes supportive discussions with students about being part of the middle-school community and how to understand and label their emotions. “With the middle-schoolers, we’ve actually seen them grow in their capacity to engage in difficult conversations,” he said.

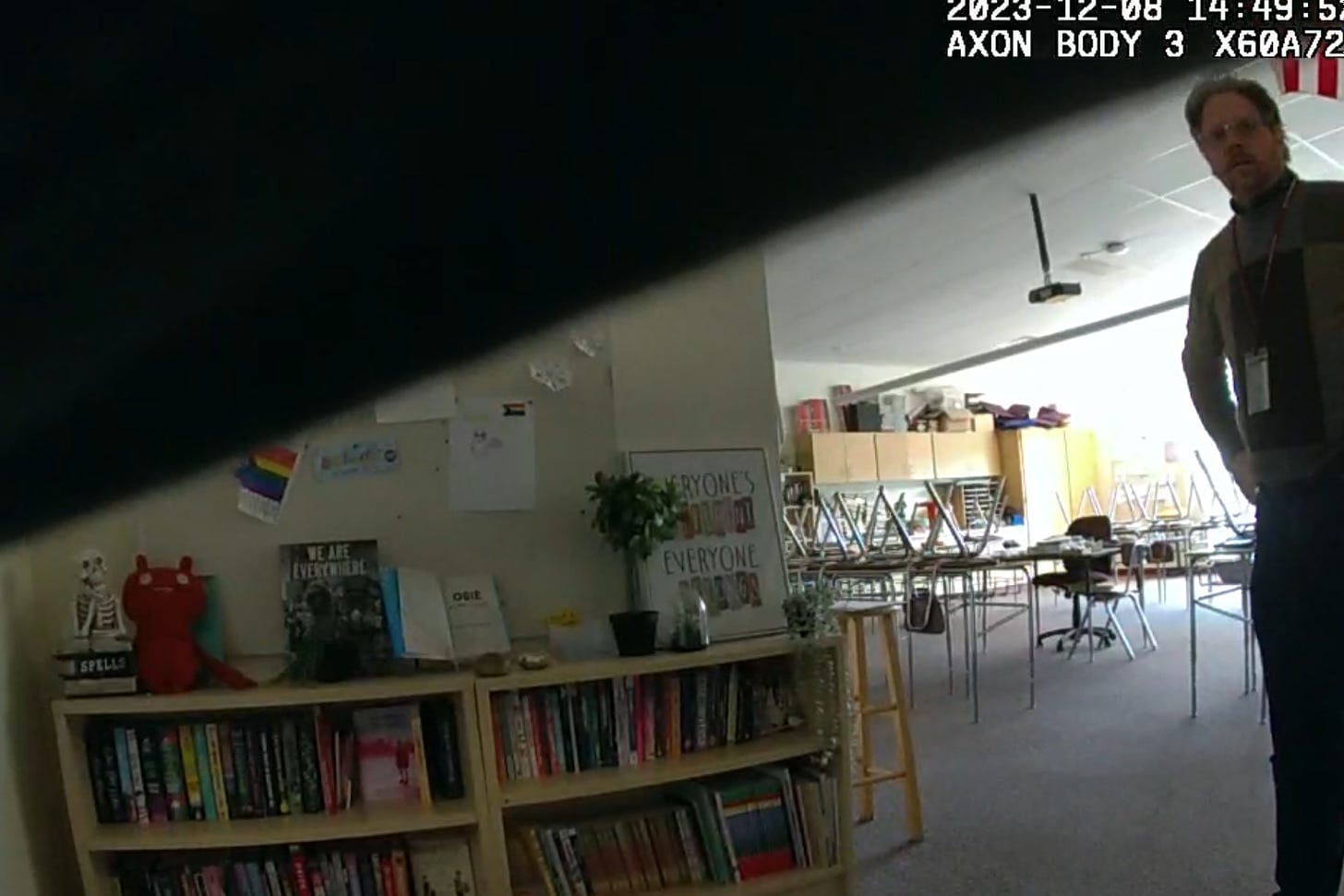

On that Friday afternoon in December, Wheat quickly realized the police visit was unusual. That feeling was based on his prior and uniformly positive experiences with the Great Barrington police combined with what Dillon had just told him on the phone. “I thought it was weird,” he said. “It felt to me like they were driving outside their lane a little bit.”

Before Wheat led the police officer to the English teacher’s classroom to search for the book, O’Brien asked him about the other allegations, including the vague charge that teachers were “meeting privately” with students. To him, that sounded outlandish. “Having somebody accuse teachers of meeting with groups of students doesn’t necessarily raise any concern for me,” he said. “That’s their job, to meet with students.”

He also discounted the other claims. “The allegation of students sitting on a teacher’s lap seemed like that was going to be really hard to investigate without time, place, context, details, or witnesses,” Wheat said. “There just wasn’t a lot to go on.” Still, he said he takes all complaints seriously, including those made anonymously, and would typically “keep an eye on things and have a conversation if it was warranted. But it’s difficult to effectively follow up on anonymous things.”

“I thought it was weird. It felt to me like they were driving outside their lane a little bit.”

—Principal Miles Wheat, on police arriving at Du Bois Middle School to search for a book

O’Brien’s report summarized their conversation. “Up to this point [Wheat] has [had] no complaints or concerns of inappropriate behavior by [the teacher] or any other teacher involved in that club or other book clubs in the school,” he wrote. He also noted that Wheat told him that classroom doors are kept open during club meetings.

Regarding “don’t tell your parents,” O’Brien wrote that Wheat “was aware the [GSA] group on occasion may suggest not talking to parents or others about what is discussed, as if a student opens up they don’t want other kids in the group discussing that with others outside.” Based on his four-page written report, titled “Narrative of Inv[estigator] O’Brien,” he didn’t ask the teacher about any of those allegations.

Storti told me that was the extent of their investigation into those claims. “The other two parts of the complaint were not substantiated, or we had no additional information,” Storti said. “We shared it with the principal, and he gave his justification, which was a reasonable justification of those two other parts of the complaint.”

Dillon agrees. “If you take out [the book] and listen carefully to what dozens of students and parents and families have said—that the teacher provided tons of support and a safe space—the only conclusion I can come to is that the allegations aren’t substantive,” he told me. “And if the police thought they were, they would have investigated it more or potentially in a different way.”

That important conversation with Wheat took place before O’Brien turned on his bodycam; only the search of the classroom and conversation about the book was captured. The Berkshire Eagle reported on the bodycam footage in a story published December 28 and included a transcript. By that time, two police reports were available that included all three allegations and a summary of Wheat’s conversation with O’Brien. But the Eagle story only quoted the police report’s discussion of the book search alongside a reference to “overhearing the teacher telling students to ‘not tell their parents’”—something the two police reports presented in different ways that left unclear whether it referred to LGBTQ books or something else.

That important conversation took place before O’Brien turned on his bodycam; only the search of the classroom and conversation about the book was captured.

The paper’s detailed coverage of the book-search affair wouldn’t note the “sitting on the teacher’s lap” allegation until January 8, three days after a sharply worded Eagle editorial called on Storti to explain what led to his decision to dispatch O’Brien to the school on December 8. It was headlined, “Our Opinion: Great Barrington Police owe the public some answers on the decision-making process that led to searching a classroom for a book.”

(Disclosure: I contributed feature articles as well as opinion and humor columns to the Eagle from 2003 to 2011.)

VIII.

Howard Cooper is a founding partner of the Boston law firm of Todd & Feld. He’s a well-known trial attorney sought out by high-profile clients: He recently represented retired Harvard Law School professor Alan Dershowitz in defamation cases that sprung from allegations that Dershowitz was among those connected to a woman trafficked by the late financier and sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. (The allegations against Dershowitz were withdrawn, as were the various defamation suits.)

Over a four-decade career, he’s represented poor and disabled residents in Framingham—winning a $1 million settlement for a local antipoverty organization; a Massachusetts judge that a jury determined was libeled by the Boston Herald; a group of Occupy Boston protestors, and a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag seeking to protect the tribe’s aboriginal rights to fish in waters off the southeastern Massachusetts town of Mattapoisett. In 2011, a Boston Globe news story described Cooper as “an aggressive cross-examiner drawn to controversial causes.”

He’s also on the board of the Massachusetts chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, which, along with GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders, wrote a late-December letter to Storti and Berkshire County District Attorney Timothy Shugrue blasting them for “unprecedented law enforcement action” in the search for the Du Bois Middle School GSA’s copy of “Gender Queer.”

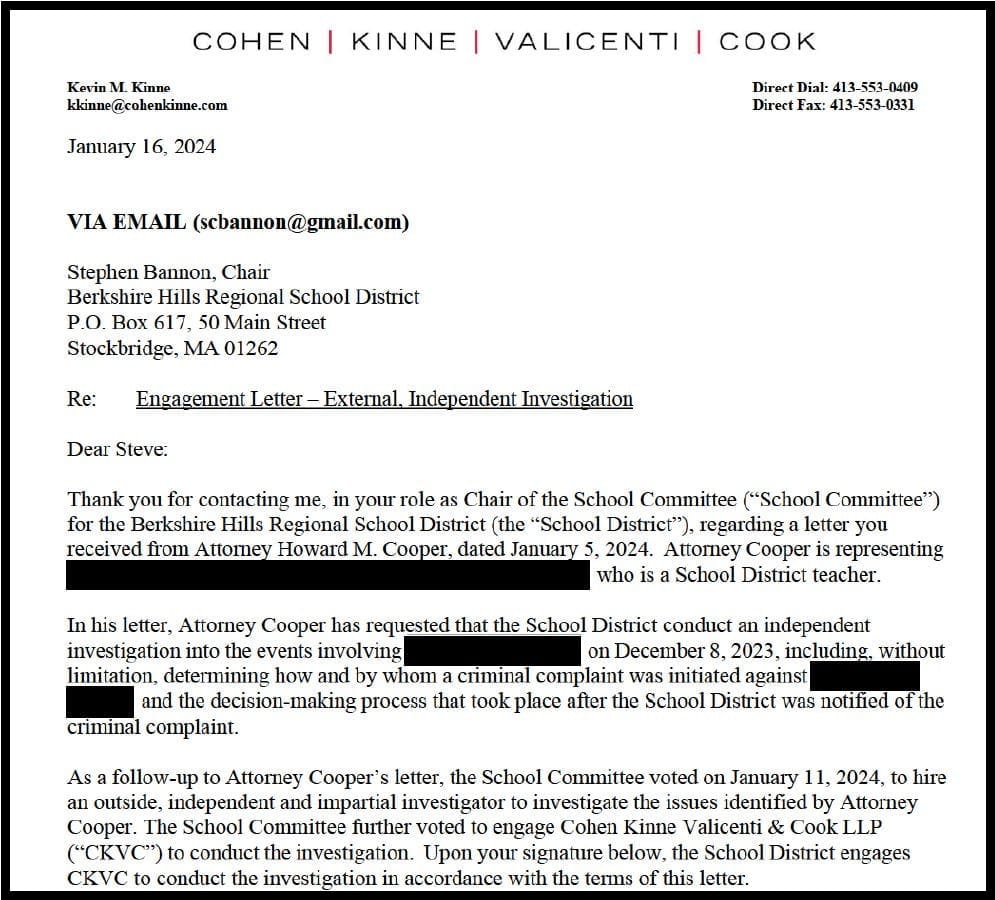

Cooper, who now also represents the Du Bois English teacher, wrote his own letter to the Great Barrington Select Board and Berkshire Hills School Committee on January 5. It demanded “an independent investigation into the events at issue including, without limitation, determining how and by whom a criminal complaint was initiated against our client and how each step of the decision-making which took place thereafter was made.”

Under a cloud of “threatened litigation”—the phrase used to describe a School Committee executive session last month—both the school district and town of Great Barrington have since initiated those investigations. Neither body has publicly shared specifics about the scope of their investigations. But according to an engagement letter between the school district and law firm Cohen, Kinne, Valicenti and Cook, acquired by The Argus in a public-records request, it will focus specifically on “investigat[ing] the issues identified by Attorney Cooper,” which includes determining the identity of the complainant and detailing the decisions made after Storti called Dillon.

“As a lawyer who does civil rights work, I have to tell you, this one is really a problem.”

—Attorney Howard Coooper

That agreement, which will pay the firm $395 an hour, says all findings will remain confidential; the School Committee will determine what information will be released, redacted, or withheld. And while the letter specifically notes that Cohen, Kinne “is not providing legal advice to the School District,” it claims the work “is intended to be covered by the attorney-client privilege”—language that may be an effort to protect the findings from the reach of Massachusetts open-records laws.

The details of the engagement letter also suggest the investigation will not examine complaints made by parents and students about homophobic harassment within the school community, some of which were shared during an intense School Committee meeting on January 11. Bannon and Dillon have both said a response to those issues and concerns is ongoing within the schools.

When I spoke to Cooper a few weeks ago, he was clearly exercised by the facts of this case. “As a lawyer who does civil rights work, I have to tell you, this one is really a problem,” he said. His voice maintained a tone of steady, mid-level exasperation. “The idea that this became a criminal investigation is frightening. We have to understand how this happened.”

He spent several minutes walking me through the bodycam footage recorded as O’Brien moved around the classroom and questioned the teacher and principal. (During the eight-minute recording, the video was mostly obscured by a shirt pocket, but most of the audio can be heard clearly.) He ticked off a list of what he said were problematic actions and statements by O’Brien, including the officer’s assumption that he had “unfettered access to materials in the room.” That included student papers that Cooper said were private.

“It is really hard to think of a more unlawful, overstepping search,” he said. O’Brien’s statement that the book contained “materials that you can’t disseminate to children” meant that O’Brien was “essentially accusing [the teacher] of engaging in a crime,” Cooper argued.

On several occasions, O’Brien asked the teacher for permission to look for things, but Cooper suggested the overall atmosphere was intimidating. “This was a terrifying experience for the teacher,” he said, noting that the police officer “shut the door behind him and placed himself between [the teacher] and the door.”

When Wheat and the teacher said the book was not in the classroom and they didn’t know where it was, O’Brien said it should be turned over to the principal when they found it. “And we’ll go from there at that point,” he said. The investigator repeatedly suggested the teacher go through other GSA books in the bookcase to “make sure there’s nothing else there depicting stuff along those lines.”

One statement during the search made headlines. “We could stay here and search every room and ask every teacher, [but] I’d rather not go that route and, you know, disrupt everything over one book that we’re looking for,” O’Brien said.

(Storti told me that on the advice of police-union counsel, O’Brien is not speaking to the media and was not interviewed by the school-district investigator. He referred any questions to O’Brien’s written report.)

“We could stay here and search every room and ask every teacher, [but] I’d rather not go that route and, you know, disrupt everything over one book that we’re looking for.”

—Great Barrington Police Officer Joseph O’Brien during a search for “Gender Queer” in a Du Bois Middle School classroom.

I asked Cooper about the non-book-related allegations and whether his client had been questioned by police or anyone else about them. “I think everybody recognizes that those allegations are not true and aren’t being pursued anywhere because they’re not true,” he said.

In a December interview with The Daily Beast, the teacher dismissed those allegations as “a horrific lie-riddled homophobic attack on the [school’s] only queer teacher, and our brave LGBTQ+ and ally students who enjoy a safe space in our voluntary Gender & Sexuality Alliance club.”

IX.

Cooper told me the priority is to identify the complainant and determine the risk, if any, to his client. (She has been on leave since early January.) “Our immediate focus has been to figure out whether there is a safety issue,” he said, “So that to the extent necessary, appropriate measures can be put in place so that she can get back to work.”

As to the complainant’s motivation, Cooper suggested a range of hypotheticals. “Was this Moms for Liberty setting this teacher up?” he asked, referring to the national organization formed to oppose pandemic school closures and mask mandates but which has pivoted to book-banning campaigns in some communities. “Or was it something less vile and more benign?”

“It is unlikely any one of us will be able to feel safe again knowing that a hateful and dangerous person could be walking around our school building and free to harass any adult or child they hate with police protection.”

—The Du Bois eighth-grade English teacher and Gender and Sexuality Alliance advisor, from a December, 2023 interview with The Daily Beast.

If it’s a parent or teacher, he said there could be discussion and “appropriate dialogue” through the district’s existing policies for evaluating or challenging materials. But he said if it was an outside group targeting the teacher, he’d be more concerned. “We have an epidemic of threats and violence going on around the country, including against teachers and librarians,” he told me. “No one’s personal safety should be jeopardized.”

In the Daily Beast interview, the teacher spoke to this concern directly. “It is unlikely any one of us will be able to feel safe again knowing that a hateful and dangerous person could be walking around our school building and free to harass any adult or child they hate with police protection,” she told the digital-news outlet.

Cooper declined to comment on whether his client suspects who made the complaint. But he said the school district has been “proactive” and listened to the teacher’s “suggestions [of] who the investigator might speak with.”

To the school principal, it’s also vital to uncover the person’s identity and motivation. “I’m a little stymied,” Wheat said. “Without that information, it’s hard for me to develop a plan for safety and support my educator. This was very serious, and it will be addressed in a very serious way.”

Meanwhile, Dillon told me he’s sought the complainant’s identity from police “several times, informally and formally.” In one mid-January email exchange acquired by The Argus through a public-records request, Dillon asked Storti and Great Barrington Town Manager Mark Pruhenski directly. “Chief Storti and Mark,” he began, “As I had previously shared with Paul, I’d like to request the name of the individual who made the complaint. Now that the investigation is closed this seems reasonable.” Storti responded that he received advice from counsel and was “in the process of interpreting it.”

“By identifying them and breaching that [anonymity], it would deter other potential witnesses and citizens from providing information to us.”

—Great Barrington Police Chief Paul Storti

Cooper said he’s unaware of any legal basis for withholding the name. But the police could, in the end, have a compelling argument: Under a portion of the state’s public-records law known as “Exemption F,” or the “investigatory exemption,” certain information can be redacted or withheld. This was established by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in a 1976 decision, Bougas v. Chief of Police of Lexington, and allows redaction of the name of a voluntary witness—indefinitely, not just while an investigation is underway—if disclosure would have a detrimental effect on future law enforcement activities. “Police departments must depend on reports from private citizens concerning possible illegal activity,” the justices wrote. “Even materials relating to an inactive investigation may require confidentiality in order to convince citizens that they may safely confide in law enforcement officials.”

Storti has declined to share the name for just that reason. “By identifying them and breaching that [anonymity], it would deter other potential witnesses and citizens from providing information to us,” he told me. “It would discourage people from coming forward. It would make our job more difficult.” That commitment also ensures the public can file complaints against police officers without being identified, he said.

While the School Committee’s investigator may independently identify the complainant, the person’s name could also be revealed if criminal charges are brought against them. “If it was determined to be a totally fake [report], and they’re doing it to try to get somebody in trouble, we have the ability to charge them with filing a false complaint,” Storti told me. When I asked if that might happen, he said, “If we had any information that led to that, yes.”

X.

If there was a moment when a more complete narrative of police and school-district decision-making on December 8 might have emerged, it was the evening of Friday, December 15. That’s when Storti, a few hours after publication of the Eagle’s first news story about the book search, submitted a draft statement about the previous-week’s events to Great Barrington’s town manager, Mark Pruhenski.

By then, the initial Eagle report had sparked an expanding, community-wide uproar. That story described the basic timeline of December 8 and focused substantially on the broader context of book challenges across the country. It ran under the headline, “Someone complained about a book in a Great Barrington classroom. Then the police showed up.” There was nothing in the story about the other two allegations—which would be detailed in a police report a week later—or their role in the decision to dispatch an officer to the school.

Based on emails acquired by The Argus in a public-records request, key changes were made to Storti’s draft statement before it was issued to the press the following morning. In his original e-mail draft, the first sentence read, “On December 8, 2023, we received a complaint that an individual has witnessed actions from a teacher that is concerning and that they observed illustrations in a book that the teacher shared with students containing illustrations of people conducting sexual acts on each other.”

But the statement issued the next day didn’t include any reference to the other allegations—the ones that, even if unfounded or maliciously fabricated, were instrumental to the police response and Dillon and Bannon’s decision to allow an officer to visit the school. Instead, the new first sentence only referenced the book: “On December 8, 2023,” it began, “the Great Barrington Police Department received a complaint from a person who witnessed what they perceived to be concerning illustrations in a book that was provided to students by a teacher at W.E.B. Dubois Middle School.”

When I asked Storti about that change, he said, “It was not my decision to take that out.” He declined to say who made the decision or the edits. Also removed was a reference to the advice provided by the district attorney during the previous week: “The police depend on the District Attorney’s Office for guidance and clarification on legal matters,” the draft said.

While he wouldn’t comment on specifics, Storti described the general process for issuing police statements. He said it’s “normal procedure” to send the department’s press releases to the town manager prior to distribution. “Before I [issue] a press release, I submit it to Mark for review,” he said. Pruhenski reviews the draft for typographical errors and for anything that might need clarification, Storti said. It’s then circulated to the town’s five Select Board members as “a heads up before it goes public.” (The Argus has a pending public-records request seeking additional documents and e-mails. In an email reply to a question about the edits made to Storti’s statement, Pruhenski told me he would respond later this week.)

Taken together, the changes and exclusions to Storti’s statement made it appear that police responded to a complaint that was only about a book illustration, and that Dillon and Bannon had agreed to allow police to visit the school on that basis alone.

By the time of Storti’s statement, it had been more than a week since O’Brien asked the school principal about those two allegations. The police, satisfied with Wheat’s response, did not investigate further. But Storti’s statement did not include that information, either. Taken together, the changes and exclusions made it appear that police responded to a complaint that was only about a book illustration, and that Dillon and Bannon had agreed to allow police to visit the school on that basis alone.

(In another email acquired by The Argus, earlier on December 15 Storti responded to an email from a concerned resident with an invitation to stop by the station: “I would like to discuss this with you so you understand what our actions were and what we did. There is a lot of misinformation out there,” he wrote.)

Over the next few days, the story went national. And two weeks later, when the bodycam footage revealed the details of O’Brien’s classroom search, it spread even more widely. By then, the narrative was set in stone: The Great Barrington police got a complaint about a book, and that was enough to send a cop to a school.

A fuller explanation of the district attorney’s role in the search for the book has also been missing from news coverage. According to the detailed timeline presented in police reports, Shugrue’s office repeatedly advised the Great Barrington police on their investigation from the afternoon of December 8 until December 14, with specific guidance related to the book.

The police department first contacted the D.A.’s office after O’Brien returned from conducting his preliminary investigation at the school. That initial conversation was summarized by Storti: “We were advised that we should try to locate the book to evaluate the illustrations to see if any potential criminal violations were warranted,” Storti wrote in his report. That included advice to secure any sign-out sheets for the book.

Early the following week, Storti spoke to the superintendent and relayed what the D.A.’s office had told him. “I advised [Dillon] of the information I was receiving from the District Attorney’s Office regarding any documents that would ascertain if any child had ever viewed the material in question,” he wrote in the police report.

Dillon told me that when Storti asked for the sign-out sheet, he declined to provide it, citing student privacy and advice from the school-district’s legal counsel. According to the police timeline, that was reported back to the D.A., who advised on next steps. “We were told we might have to plan for having to write a search warrant to obtain any information regarding this matter,” Storti wrote.

That engagement between the D.A. and police continued until December 14, when two things happened in close succession: Shugrue spoke directly to Dillon, who advocated for letting the school district handle the matter, and Shugrue was contacted by Berkshire Eagle reporter Heather Bellow, who was preparing to file the first news story on the incident. Shugrue quickly issued a statement: “The complaint that was filed did not involve criminal activity,” he said. “Therefore, the Great Barrington Police Department and our office have closed the matter.” Storti told the Eagle that his department was engaged with both the school district and the district attorney to “make sure that further investigation isn’t warranted.”

Last month I spoke several times with Shugrue’s spokesperson, Julia Sabourin. On December 18, she had defended the law-enforcement response in an interview with WGBH News. “Police are duty bound to investigate reported criminal acts, and they can’t choose when to respond and when not to,” she told the outlet.

When we spoke, Sabourin said repeatedly that the district attorney never opened an investigation and only offered advice to the Great Barrington police. She provided what she said was a “more detailed” statement from Shugrue. It described the basic chronology of December 8, noting that police visited the school before contacting the district attorney. It continued, “I am always concerned when there is an allegation regarding children and abuse and take these allegations seriously. Once I ascertained that the anonymous complaint was solely surrounding the illustrations in the book Gender Queer in its original published form, I advised the Great Barrington Police Department to close the inquiry into said matter wherein there was no criminal activity.”

When I asked Sabourin about Shugrue’s reference to “children and abuse,” and his claim that law enforcement became involved “solely” because of illustrations in the book, she suggested the complaint’s other allegations were never shared with the D.A. “What was communicated primarily to our office was obscene pornographic material in an item in a school building,” she said. “So that’s what came across in the call to our office. As for the other two items, we were not privy to that,” Sabourin said.

Storti, however, told me that Great Barrington police shared details of all three allegations with the D.A.’s office in the call after O’Brien left the school on December 8. “That’s when I said, ‘We need some guidance and advice from the DA’s office,’” he said. “You know, ‘What should we do in this situation?’ That’s why we reached out.”

(Sabourin did not respond to multiple e-mails seeking clarification.)

XI.

On January 8, at the first meeting of the Great Barrington Select Board since the incident became public, Steve Bannon, the chair, read a statement that reinforced the now-well-established narrative. It didn’t mention the other allegations, the role they played in decision-making on December 8, or that police had examined and dismissed them. He may have decided—as Dillon said he did initially—that because they might be unfounded or personnel-related, it was better not to repeat them.

“As many of you are aware,” he said as the meeting opened, “our police department received a complaint on December 8th from an individual who expressed concern about images and content in a book being provided to students at the W.E.B. Du Bois Middle School.” He said a review of police policies was underway.

In response to several interview requests and e-mailed questions, Bannon told me this week that he’s been advised by lawyers for both the school district and the town not to speak publicly on this matter “due to pending litigation.” He said it’s the same reason the School Committee and Select Board have held executive sessions since early January, though Bannon has spoken about the incident in several public meetings since then.

During time set aside for media questions at the Select Board’s January 22 meeting, I asked him about the potential for conflicts of interest and whether he was considering recusal, particularly in light of threatened litigation against one or both of the town of Great Barrington and the Berkshire Hills School District. “There’s no reason to recuse myself,” he said. “My role is simply as one member of each board. As chair I have no more authority than anyone else and I’m not privy to any more information than any of the other board members.”

That may not be entirely accurate, particularly as the School Committee and town of Great Barrington undertake separate, confidential investigations. As a result of his dual roles, Bannon will receive confidential information and separate legal advice from each entity that is not available to members of both boards, and that he’s not permitted to share between boards—something that creates almost irreconcilable complexity.

“There’s no reason to recuse myself. My role is simply as one member of each board. As chair I have no more authority than anyone else and I’m not privy to any more information than any of the other board members.”

—Steve Bannon, chair of both the Great Barrington Select Board and the Berkshire Hills Regional School District

Bannon’s participation in phone conversations and decisions made on December 8 and afterwards may also contribute to a Gordian Knot of actual and apparent conflicts, particularly if those decisions become central to any litigation filed against the district, town, police department, or any of the individuals involved.

It’s not the first time that questions about Bannon’s multiple roles have emerged, even as fellow board members and residents express appreciation for the time and energy he has long invested in town and school-district affairs—and those residents continue to re-elect him to both boards.

There was some discussion of the issue when he was first elected to the Select Board in 2010, and then again when chosen Select Board chair in a three-to-two vote in May, 2018. At that time, former Select Board members Ed Abrahams and Bill Cooke felt that one person chairing both boards was problematic. They were particularly concerned about the relationships and balance-of-power among the three school-district towns.

“I think it’s a big mistake,” Abrahams said before the vote. “It’s nothing against you, Steve.”

“If I saw a problem, I wouldn’t have taken it,” Bannon said.

The Massachusetts Municipal Association’s guide for Select Board members notes that “actions approved by a board or community could eventually be overturned due to conflict issues.” While that process under the state ethics law can be onerous, avoiding real or perceived conflicts is central to guidance provided to municipal officials by the State Ethics Commission. If one member of a Select Board is recused, the other four members can transact its business. The Berkshire Hills School Committee has ten members; it can also continue to operate with some members missing or recused.

Indeed, one member of the School Committee has already stepped aside in this matter. Richard Dohoney, first elected to the School Committee in 2012 and currently its vice chair, is an assistant attorney general in Massachusetts and has recused himself from discussions related to the book-search incident. He didn’t attend the board’s January 11 executive session or the public meeting when it voted to approve an independent investigation.

Dohoney also stepped out of the room during the recent discussion and vote on a resolution calling on the Great Barrington Police Department to conduct an internal investigation. In that case, Bannon participated and voted. He also spoke out against a proposal to toughen language that described the police department’s actions.

In an email, Dohoney told me his recusal is “to avoid the appearance of any potential conflict,” citing his employment. Prior to his current position with the attorney general, he also spent four years in county law enforcement as a deputy district attorney under former Berkshire County District Attorney Andrea Harrington. The School Committee’s policy subcommittee is also crafting a new memorandum of understanding with the Great Barrington Police Department and has received advice and a template document from the attorney general’s office.

XII.

During our first conversation in mid-January, I asked Peter Dillon how district students were doing, given the glare of national-media attention and the difficult, sensitive subjects in the mix. “On the one hand, they’re doing okay, and they’re resilient,” he told me. “On the other hand, they’re struggling in a lot of different ways.”

The impact on middle-schoolers and those involved with GSA may be more specific. “There may be some students who are on the edge of questioning and they’re not doing that right now,” Dillon said. “I think that can be really hard. And there are other students who are upset because this is a distraction, and they miss their eighth-grade English teacher and want to get on with learning.”

“What this has surfaced is core to all our work, which is how young people and adults are treated … it’s created lots of space for conversation and engagement.”

—BHRSD Superintendent Peter Dillon

Dillon conceded the controversy was taking a lot of time at a moment in the school-year cycle when administrators are focused on next year’s budget and ongoing planning for a new high school. But he wouldn’t characterize it as a distraction. “What this has surfaced is core to all our work, which is how young people and adults are treated,” he said. “So, the silver lining is that it’s created lots of space for conversation and engagement.”

Still, the last two months have clearly taken a toll. “I often describe myself as compulsively optimistic, and you sort of have to be. But I’ve taken some lumps,” he said. “This is hard and challenging. But I think we can rebuild a level of trust and start to move forward and learn from this.”

From the beginning, Dillon has been frank about his errors and missteps. For example, in his December 14 e-mail to the school community, hours before the first news story appeared, he suggested that controversial books like “Gender Queer” could be reviewed by an ad-hoc committee. He has since walked back that idea.

“Removing or restricting queer books in libraries and schools is like cutting a lifeline for queer youth, who might not yet even know what terms to ask Google to find out more about their own identities, bodies and health.”

—“Gender Queer” author Maia Kobabe

“If I could un-say that I would un-say that,” he said, calling his argument “a little flawed.” A book like “Gender Queer” is different from curriculum or other materials that parents might opt-out of through an existing process, he explained. “It’s an ancillary text that is used as a [GSA] resource, so it doesn’t fall under the same guidelines as a text in a health-education class.”

Kobabe, the book’s author, wrote about the importance of access to these kinds of books in a 2021 Washington Post opinion column—something rooted in eir own path of personal discovery and from years working in libraries. “Queer youth are often forced to look outside their own homes, and outside the education system, to find information on who they are,” e wrote. “Removing or restricting queer books in libraries and schools is like cutting a lifeline for queer youth, who might not yet even know what terms to ask Google to find out more about their own identities, bodies and health.”

Soon after the police questioned the eighth-grade English teacher and GSA advisor in her classroom, she took to social media to sharply criticize the police and defend educators’ expertise. “How on earth is a cop more qualified to decide what books are OK to be in an educational setting for teens?” she wrote online, according to the Eagle. “Respect for parental and educational guidance? Absolutely! But a police officer should never, ever search classrooms for award-winning literature to remove. Period.”

The Du Bois librarian, Jennifer Guerin, chimed in a few days later, telling the Eagle, “It’s about the freedom to read. It’s about providing voluntary access to a well-written, highly acclaimed resource in a safe place for a teenager who might want or need it.”

Wheat told me he’d like to get his teacher back in the classroom instructing students and advising the GSA. In the meantime, a long-term substitute and a school counselor have stepped in, respectively.

“We want to make sure the student experience in the GSA is not interrupted,” he said. “I think the search impacted the whole school community, but it didn’t impact the whole school community equally.” The Du Bois GSA is being supported by members of Monument’s GSA and receiving additional help from Railroad Street Youth Project—a new engagement with the middle school that the group’s executive director, Ananda Timpane, told me is likely to continue.

“I didn’t anticipate how upsetting that search would be for the teacher … I should have thought about that more deeply.”

—Du Bois Principal Miles Wheat

Like Dillon, Wheat has been transparent about his own mistakes—particulalry the impact of the classroom search on the teacher.

“We’ve always had a good relationship with the police,” he told me. “Whenever I’ve called them, they’ve shown up with the right kind of help to make the situation safer.”

That includes mental-health emergencies: He shared a moving story of an officer arriving at the school in response to a student in crisis and running away from the school. The officer who responded to the call was the child’s coach in a youth-sports league. “The kid just broke down crying and gave the officer a big hug. The officer put him in the car and took him home,” Wheat said.

But he now realizes that attitude toward police isn’t universal. “All of this is leading up to me making a tremendous mistake,” he said. “This particular police department, I am very comfortable with them.” But on that Friday afternoon in December, he said, “I didn’t anticipate how upsetting that search would be for the teacher … I should have thought about that more deeply.”

“I want one-hundred-percent transparency.”

—Great Barrington Police Chief Paul Storti

As for Storti, he told me last week that he fully supports the additional investigation authorized by Great Barrington’s Select Board. He’s completed his department’s standard after-action review and a deeper examination of relevant department policies. He has revisions in mind but is waiting for ideas that may come out of the town’s investigation. “I want one-hundred-percent transparency,” he said. “I want people to know what we did and why we did it. [And] any constructive information we can gather from the independent investigation is important.”

The book search and its continuing fallout have brought into sharp focus the impact of police decisions and actions on individuals and a community. That’s something Storti spoke about candidly when he became chief of police. “You have to understand that our actions have so many ripple effects,” he told The Berkshire Edge in 2021. “Like giving people a speeding ticket. Yes, you’re out there to protect the public and slow people down. But on the other side of the coin, there’s an effect on that person’s family. That ticket could be their rent or food for the month. There’s a time to act. But you also have to understand the collateral damage that we do.”