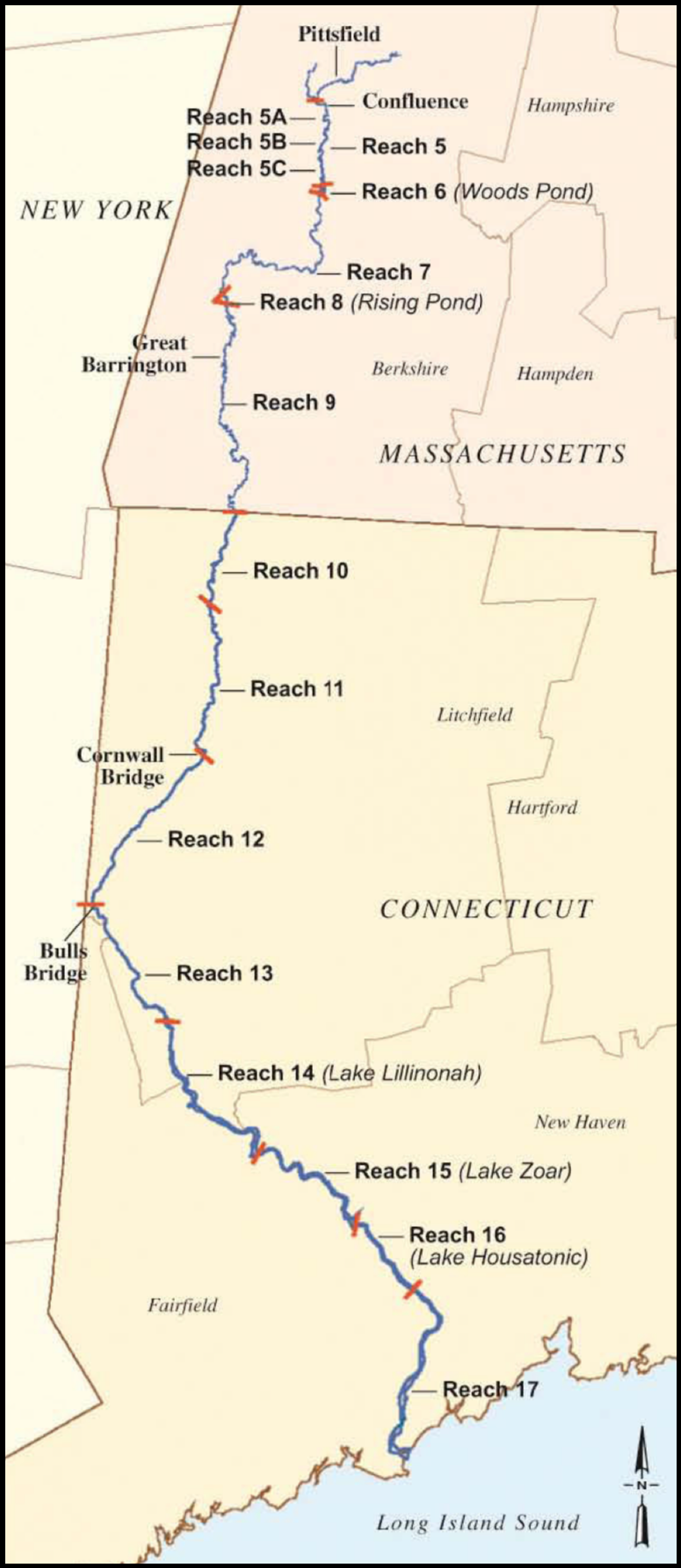

From its headwaters near Pittsfield, Massachusetts, the Housatonic River flows south for one hundred and forty-nine miles, winding through the southern Berkshires and across Connecticut until it reaches Long Island Sound near a barrier beach called Milford Point. On its way there, it more or less evenly bisects a Massachusetts House of Representatives district known as the Third Berkshire.

More noteworthy than how it splits that swath of southwestern Massachusetts—the largest, in square miles, of any state-house district in the Commonwealth—is how, over several decades, the battle to restore a polluted river and protect the health of those living nearby created sharp divisions in the legislative district’s eighteen communities.

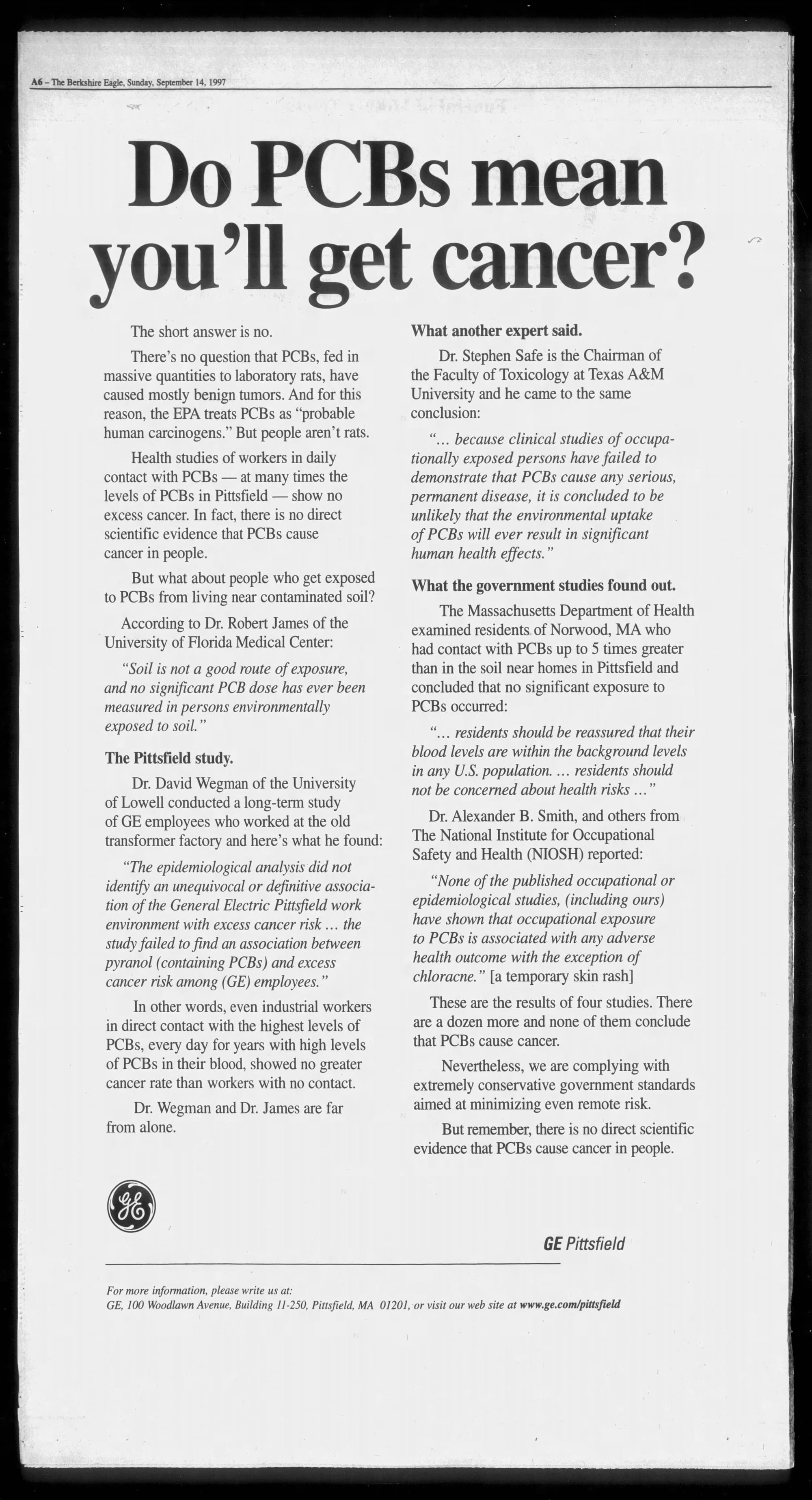

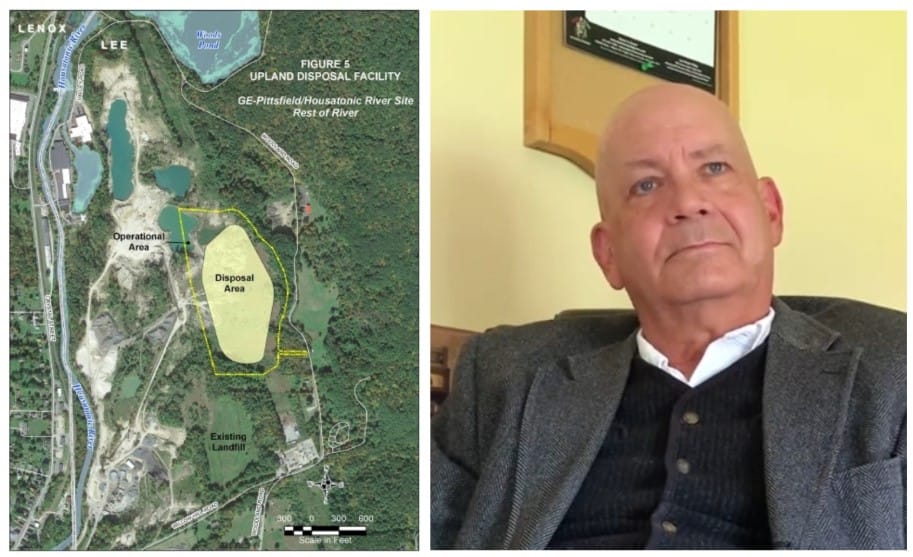

On one side are those who vigorously oppose a pending Environmental Protection Agency-managed plan, called “Rest of River,” to remove some amount of polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, from the river and its floodplains—present in large quantity after decades of dumping and spillage of toxic transformer-insulating fluids from a massive General Electric manufacturing plant in Pittsfield—and then deposit more than a million cubic yards of tainted soil and sediment in a new engineered landfill in the town of Lee.

They may oppose it for cleaning up too many PCBs or too few, for taking too long or not long enough, or for ignoring bioremediation, incineration, and other technologies they say could do the job—even if at much higher cost. Without question, many oppose the plan because it permanently saddles the historically working-class town of Lee with a toxic-waste dump—however well-built and leak-monitored the E.P.A. insists it will be.

On another side are those who see the planned thirteen-year-long project—which emerged after more than a decade of legal and bureaucratic fights between and among state and federal regulators, corporate lawyers, environmental activists, courts, everyday citizens, mediators, and local elected officials—as an overdue, necessary evil. They say an agreement reached nearly five years ago was the best that could be achieved when five small communities along the river—with a total population of less than 25,000—faced off against the wealth, political power, and bottomless legal resources of G.E., a longtime Fortune 100 company. G.E. Aerospace, which earlier this year inherited the General Electric brand name and legacy, is legally required to clean up the chemical pollution put into the Housatonic by its corporate forbears and pay a bill estimated at more than six hundred million dollars. With shareholder value at front-of-corporate mind, there’s little argument that the company is motivated to keep expenses to a minimum.

And there’s at least one more side: Those who may not like the prospect of a PCB dump in the heart of tourism-reliant Berkshire County, or who might be outraged by a still-confidential process that led to the agreement’s approval in February, 2020, but who are working to leverage every opportunity to ensure the planned remediation is done well and the new landfill is safe. At least, that is, within the confines of an E.P.A.-issued permit that a federal court last year ruled comports with the law. And besides, they say, the project is already well in motion; derailing it now could mean that probably cancer-and-other-illness-causing PCBs remain where they are for many more years, leaving little hope for a safe, healthy Housatonic River fully restored for some future generation.

Draw a Venn diagram of these groups, and at the overlapping center you’ll find Bob Jones, a seventy-one-year-old member of Lee’s governing Select Board. His voice—deep, sonorous, and made for the age of radio—has been among the most prominent heard since 2020 in nonstop wrangling over the project, its planned twenty-acre landfill site, and an overall remediation plan that, he says, shortchanges both the ecological health of the river and the human-health prospects of river-corridor residents current and future.

His skepticism starts with process. “I think the Rest of River agreement was intentionally structured to divide the [five] towns,” Jones, who was elected during a multi-year sweep that replaced all three Lee Select Board members who voted for the deal, told me recently. “Five representatives, in a closed room, trying to bang out some sort of agreement, being told there’s going to be at least one dump but there could be two or three,” he said. “Some of those representatives weren’t even elected officials,” he said, referring to members of a five-town municipal committee that negotiated with G.E., E.P.A., environmental groups, and others.

Today he has two primary goals that, he says, are widely shared: “To not have another toxic-waste dump anywhere in Berkshire County”—beyond controversial locations in Pittsfield that were constructed with E.P.A. approval during earlier phases of the PCB-remediation project—“and to have an actual clean-up of the river. The current Rest of River agreement does not address that at all,” he said. “It’s just moving the stuff from one place to another.”

Strikingly bald and often wearing suspenders and a cowboy-style hat, Jones is knowledgeable, politic, passionate, and notably more temperate in speech and manner than some others engaged in the Rest of River debate. Listen to him speak—often frustrated, but measured—and you won’t hear the same tone of distrust, anger, fear, and blame that can electrify the air at public events related to PCBs and the river—where tempers quickly run hot, accusations fly, and motives are routinely questioned.

Indeed, at meetings held over the last few years in Lee and neighboring Lenox, whose eastern border is a stone’s throw from the planned “upland disposal facility”—as it’s been named by G.E. and federal regulators—local police officers were always visible at the back of the room.

After a recent meeting of Lee’s twelve-person PCB Advisory Committee, established this past April to help the town navigate what will be many years of work, Jones told me, “This is not what I thought I’d be doing at seventy-one.” He said he just wants the river to be clean. “We want people to be safe, and we want their health concerns to be addressed. These are just basic needs,” he said.

The last twelve months have been a busy—and critical—period for the Rest of River process. It’s been filled with submissions, reviews, presentations, forums, and public-comment periods for key project plans from G.E. that E.P.A. must approve: The latest iteration of a design for the landfill and various remediation work plans; a “quality-of-life” plan that aims to monitor and temper impacts on nearby residents, communities, and infrastructure; and a transportation and disposal plan that details how soil and sediment removed from the river and nearby floodplains will be transported to the new facility—and, for less than ten percent of the material, including the portion with higher levels of PCB contamination, to out-of-state facilities.

All agree that the plan will remove no more than approximately thirty percent of PCBs in the river and nearby, but E.P.A. has long said it will be more protective to human health and the environment than leaving the PCBs where they are.

Into this busy moment came the first open-seat campaign to represent the Third Berkshire since 2002, when a Lenox electrician and longtime town selectman, William “Smitty” Pignatelli, was first elected and sent to Boston. In early February, he announced plans to retire. And after a six-month-long Democratic-primary campaign between three candidates, Leigh Davis, an affordable-housing advocate and member of Great Barrington’s Select Board, emerged victorious to face an independent candidate, Lenox Select Board member Marybeth Mitts, in the November 5th general election.

Government bureaucracy and complicated projects like Rest of River are not unfamiliar to Mitts. Her career has included work for federal agencies including the U.S. Navy and Department of Housing and Urban Development. She’s helped municipalities and universities seek and manage grant funds and develop strategic plans, particularly related to housing. After years of following her Navy-doctor husband to posts near and far, their family settled in Lenox more than twenty years ago.

Davis, who like Mitts is a mother of three, has been a Great Barrington resident for fifteen years. As she tells the story, she discovered the town by accident, stranded by a snowstorm during a visit from Galway, Ireland where she taught film as a college professor. She describes starting out here doing a variety of jobs in what she and others in the region call “the Berkshires shuffle,” and in recent years has worked in development and communications at Construct, a Great Barrington affordable- and transitional-housing nonprofit.

In conversation, Davis is confident and sometimes intense, but also has an easy laugh. Excited about an idea or proposal, she speaks at a rapid clip. At local-government meetings and campaign forums, she’s often busy scribbling with a stylus or referring to notes on an ever-present tablet computer.

Despite the first competitive, open-seat race in more than two decades, news coverage has been relatively light. The county-wide Berkshire Eagle newspaper, digital outlets like The Berkshire Edge and iBerkshires.com, and nearby NPR affiliates have provided basic profiles and coverage of a few candidate forums—including an Eagle-hosted general-election debate. The Edge has printed a slew of Davis’s press releases, complete with her campaign’s contact information. (Disclosure: I have been a contributing writer for both the Eagle and the Edge.)

The primary and general-election campaigns have featured a few blips of contentiousness: Over Mitts’s accidental choice to run as an independent after she missed a party-registration deadline; a kerfuffle around a last-minute expenditure by a realtor’s lobby in support of Davis’s closest primary opponent; and, in this era’s political atmosphere, the to-be-expected social-media flare-ups.

Davis has run a disciplined campaign, comfortably checking the progressive-politics boxes you’d expect in a deep-blue county. She’s secured buckets of endorsements not only from local, state, and national Democrats—including recently from the state’s governor, Maura Healey, and both of its U.S. senators—but also from labor unions, environmental organizations, and other advocacy groups. Supporters of other candidates this year have suggested that makes her beholden to party bosses in the transparency-challenged state legislature, and to “special interests.” In the Eagle debate and while campaigning, Davis countered that her endorsements were hard won, reflect her values, and has said it means she’ll have governing partners at all levels from the get-go.

Marybeth Mitts, center, and Leigh Davis, right, at a Berkshire Eagle-hosted debate last month. The Eagle's executive editor, Kevin Moran, is at left. (CTSB-TV/YouTube)

On September 3, Davis won the Democratic primary with fifty-six percent of the vote, defeating two members of the Stockbridge Select Board: Patrick White, who received thirty-seven percent, and Jamie Minacci with seven percent.

In the ongoing battle of letters-to-the-editor that has raged before and since the primary, her supporters tout Davis’s work on housing affordability and availability, which includes successfully advancing a Great Barrington bylaw that put modest limits on short-term rentals—but, significantly, blocked corporate ownership—after a contentious and often personal battle with local and national real-estate interests. The candidate and her supporters note her many endorsements from well-known Democrats like Elizabeth Warren and U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley, and a policy focus on economic development and climate solutions.

Those championing Mitts’s candidacy point to her long experience, deep knowledge of government processes at various levels, her six years of hard work to help add at least sixty-five market-rate and affordable-housing units to Lenox—she has served for years on the town’s Affordable Housing Trust—and a comfort level with policy details.

Mitts has argued that an independent candidacy, even if accidental, reflects her approach to governing and is a sign that she’ll represent everyone—though she says she’ll caucus with the Democrats, who currently hold 133 of 160 seats in the legislature. She’s said at various times that if she wins, she might—and in at least one case, will “absolutely”—change her party affiliation to Democrat, and at others that she’ll remain unaffiliated.

The Eagle’s editorial board recently endorsed Mitts. If elected, and chooses to remain unaffiliated with a political party, she would be one of only two independents in the legislature.

On the Rest of River settlement agreement, a tough vote versus a conflict-of-interest recusal

One key distinction between the candidates on Rest of River is no secret: Mitts is one of the Select Board members from the five directly impacted towns who voted to approve the controversial 2020 settlement agreement. (While many have discussed their votes publicly, executive-session minutes that include those recorded votes have not been made public. Last week, The Argus filed Open Meeting Law-related requests with all five towns seeking their release.)

But two Select Board members have said they recused themselves from the discussion and vote: Neal Maxymillian, currently the chair of the Lenox Select Board, whose civil and environmental construction firm has long done work for GE’s PCB-remediation projects, and Davis, who at the time she was first elected to her town’s governing body, in May, 2019, and into 2021, worked for a real-estate developer whose Eagle Mill Redevelopment project, in Lee, sits alongside the river and near the Eagle Mill Dam, behind which PCB pollution is concentrated. Maxymillian and Davis have both said they were advised by lawyers at the state ethics commission to not participate in the matter because of those conflicts.

A spokesperson for the commission told me that its advice to municipal employees and elected officials about complying with state ethics laws is confidential. It also can’t confirm or deny if any elected official has sought advice, or what that advice is. It provides detailed online resources that explain the state’s ethics law, as well as overseeing mandated biannual-ethics training for all municipal office-holders.

In an extensive explanation posted to her campaign website in mid-July, Davis noted her recusal, what she described as longstanding opposition to a local PCB dump, and her recent work on the issue. “Let me be incredibly clear about the fact that I was not involved in any of the discussions leading to the 2020 Settlement Agreement. Period,” she wrote. “I was required to recuse myself from all meetings that pertained to the issue when I joined the Selectboard. I did not vote for the dump, I was not allowed to speak against it, or learn about the negotiations as they were developing,” the statement says.

While Mitts has spoken about Rest of River at candidate forums and in media interviews, she has not posted any information about the issue, or her vote, on her campaign website. (In an email, she told me she’s “happier to talk to people about this issue.”)

Those who voted to approve the agreement, including Mitts, and those who support it today say it was the best option at a moment when the alternatives seemed bleak: A deep-pocketed, heavily lawyered G.E. had leveraged a key precedent—the previously approved consolidation of PCB-tainted material in dumps in Pittsfield during earlier phases of remediation performed under a 2000 consent decree—to argue against the E.P.A.’s 2016 requirement to ship all dredged PCBs out of state. The company had already secured rights to land in three locations: The one in Lee eventually selected for the dump; another in Lee near the Lee/Lenox border; and a third in Great Barrington’s Housatonic village near Rising Pond. The threat of endless litigation, no remediation for years, and the possibility of three dumps were primary concerns.

While it did include a new “overbuilt” landfill in Lee, supporters have long highlighted the agreement’s expanded scope, which includes less capping and more PCB removal, as well as an end to protracted litigation that could have delayed any remediation indefinitely. The towns also received cash payments: $25 million each to Lee and Lenox; and $1.5 million each to Sheffield, Stockbridge, and Great Barrington. (Pittsfield also received $8 million.)

When I spoke with Mitts at a Lenox coffee shop last week, she had a cheerful, policy-wonk vibe: At one point, looking through rimless glasses, she spoke at length about the need for the legislature to spin up its own bipartisan research and analysis arm to better educate representatives on complex issues. “There should be fiscal analysis and data analysis being done in-house in the legislature,” she said. “It’s ludicrous to me that doesn’t exist.”

Mitts described the meeting of the Lenox Select Board when it voted to approve the agreement in late 2019 or early 2020, and said she asked a lot of questions. “We were all pretty agonized about it, knowing that this is going to be right across the river from Lenox Dale,” she said. “Three of the four of us that were on the board at that point lived within a mile of the upland disposal facility.”

She was keenly aware of the other possibilities. “They could have taken everything out of the river and just built concrete trenches and put it all in Berkshire County,” she said. “That was one of their options.”

At a February 19, 2020 information forum in Lee, Mitts explained her rationale for supporting the Rest of River settlement agreement. (CTSB-TV/YouTube)

Mitts wouldn’t speculate on what might have unfolded if the agreement had been voted down or later scuttled, but said it was better than the alternatives. “Nothing is perfect in this world, but I think leaving [PCBs] in the river as an open toxic-waste dump is the worst decision that we could make,” she said. “Leaving it alone I don’t think helps us in the long run at all.”

She said she’s confident in the scientists and project managers at E.P.A. who are overseeing the work, perhaps reflecting her years of work for, and with, federal-government agencies. “I think they’re doing the best job they can do. I have a lot of faith that there are very intelligent people on this project,” she said. “You don’t get to work for an agency like E.P.A. by being somebody off the street. You generally have a degree in environmental studies, you’ve got a master’s [degree]. These people have been doing this most of their lives, if not their entire careers.”

She’s also comfortable with the location and design of the landfill, which will be constructed with multiple liners and protective features at the site of a former gravel pit about a thousand feet from the river and, regulators say, no less than fifteen feet above the groundwater high-water mark—details that still concern those critical of E.P.A.’s approval of the site as well as the design. But Mitts said the location and engineering will do the job safely. “The way I see it, it’s an empty quarry. It’s a vessel, if you will,” she said, describing the landscape. “And with the liners and the leachate system they plan on putting in, it sounds like a good plan.” (A leachate system captures tainted water for treatment or removal.)

For Davis, 'rigorous oversight' and questions about Rest of River's history

For her part, Davis said she’s not looked at the details of E.P.A.’s plans to oversee operations during the cleanup and at the new engineered landfill. “I haven’t yet had the opportunity to delve closely into the specifics of the E.P.A.’s processes and oversight for the site,” she wrote this week via text, but said she wants “full transparency, public involvement, and rigorous oversight” as the project moves forward. She has said that if elected, she will “advocate for a cleanup that holds G.E. accountable, prioritizes human health and safety, and fosters collaboration and transparency across our towns.”

In an interview in late February shortly after announcing her candidacy, Davis said she was focused on that accountability during the long implementation phase of the agreement, acknowledging there will be a new PCB landfill in Lee. “It’s there. We kind of missed that boat, so now we just need to make sure they do it right,” she said. “It is what it is, the [legal] appeals didn’t go anywhere, this is what we have to work with.”

She noted in her July website statement that she had been opposed to it. “Let me make one other point clear—I was very much opposed to the idea of a local landfill. Polluting our community to clean the river was never a trade I approved of,” she wrote.

Last month I asked Davis if she would have voted against the settlement agreement, and the dump in Lee, if she had not recused. She said, “I don’t know, because I don’t have enough information. I wasn’t part of that discussion. But obviously we shouldn’t have a dump in Lee. But where is it going to go?” She also declined to say how she would have voted if the agreement had included a landfill near Rising Pond, in her town of Great Barrington. “I’m not going to answer hypotheticals,” she said. Still, she said had she been there for the vote, she would have raised concerns that “residents were not sitting at the table.”

During our interviews and as she’s campaigned, Davis’s rhetoric on Rest of River sometimes aligned with goals of those bitterly opposed to any PCB landfill in Lee. At other times, she seemed to overlook the project’s long and contentious history. “Why should we have this Superfund site in Lee?” she asked during an interview last week. “They’re saying that only ten percent, the most-toxic materials, will be taken out [of the area]. Why are we settling for ten percent? Why can’t we say twenty, thirty, forty? Why should we be stuck with ninety percent of the materials in the Berkshires?”

The size and location of the landfill, and how much PCB-laden soil and sediment will be removed from the river and its floodplains and placed there, were both at the center of the regulatory and legal battle that went on for more than a decade. It’s what led to the controversial closed-door mediation that began in 2018, and, ultimately, to the settlement agreement and E.P.A.-issued permit that includes those details—the ones that have upset many residents, particularly in Lee.

At a public forum last November, Dean Tagliaferro, the E.P.A. project manager and Pittsfield resident who has worked on the Pittsfield and Housatonic PCB-remediation projects for a quarter-century, said the E.P.A. will continue to be responsive to feedback on project plans as they are unveiled, but said he was focused on moving things forward. “Do what you got to do to try and stop the dump,” he told one resident, “but my job is to implement the remedy.”

Davis said that even if the dump can’t be eliminated, she’d like it to be smaller. “I’m focusing on decreasing the size of the dump. This is a new angle I’m exploring with a few others,” she said. “I don’t know if it’s realistic to open that up and bring that to the forefront, but it’s something that I’ve always questioned.” She said she’ll also continue to focus on “the quality of life for residential neighborhoods that will be impacted by the transportation plan.”

It’s unclear how Davis would force a change to the overall size of the new landfill or the amount of PCB-laden material that will be sent there or out-of-state. But she said she’ll continue advocating for changes to the court-approved remedy while also engaging in “what’s in front of us,” like transportation and quality-of-life plans.

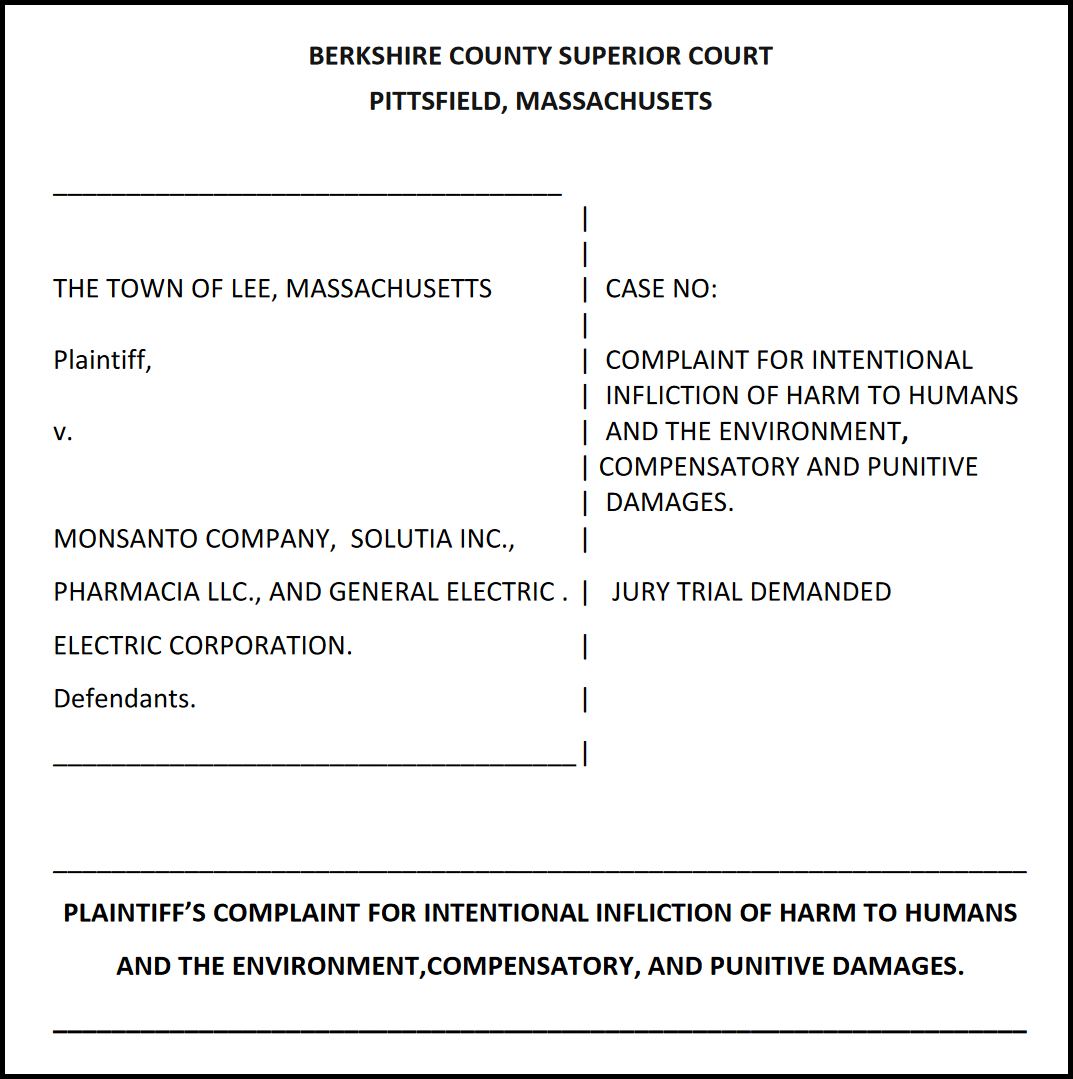

Leaders in Lee hope that a lawsuit the town filed earlier this year against Monsanto, which manufactured PCBs for half a century beginning in the 1930s, and against G.E., could provide some leverage for those larger goals. The suit alleges the companies knew about PCB toxicity and human-health dangers decades before the chemical was banned in the 1970s.

If successful—and particularly if it delivers a large monetary award—they think it could lead to a substantially revised remediation plan that sends all PCB-laden materials to out-of-state facilities, eliminating any need for the new landfill. Similar suits against Monsanto in recent years for environmental and human-health impacts have sometimes produced those large awards. For example, in July Monsanto agreed to a $160 million settlement with the city of Seattle over PCB contamination of the Duwamish River. As part of that settlement, Monsanto did not admit any wrongdoing.

And last December, a jury agreed that PCB contamination was the cause of cancer and other illnesses suffered by employees and students at a Seattle-area school, awarding the plaintiffs $857 million. That award was reduced by a judge to $438 million earlier this year. Monsanto has appealed the verdict.

Lee’s case is in federal court, where the defendants this summer moved to have it dismissed, suggesting in part that the Rest of River agreement does not allow the town to also sue the companies for damages. Separately, at least nine other cases filed last year by a Lenox-born, Philadelphia-based attorney on behalf of Pittsfield residents who say they were sickened by PCBs—including cancers caused by a PCB landfill located adjacent to Pittsfield’s Allendale Elementary School—are also pending.

Jones also told me that he sees “loopholes” that “leave some of the major pieces of the settlement agreement open for debate.” And he’s clearly focused on finding and exploiting them: During a strategy discussion during a PCB Advisory Committee meeting in in April, Jones said, “I wouldn’t be sitting here if I didn’t think that we have some arrows in our quiver, in terms of stopping this dump.”

(G.E. is due to submit the latest iteration of its landfill-design plan and an operation, monitoring, and maintenance plan by December 20. Public comments on those plans will be accepted until February 3, 2025.)

Following a session of the advisory committee she attended in mid-October, Davis told me that as state representative she’d also work to bring funds to the region that might catalyze innovation and business development around bioremediation technologies. She suggested that PCB-contaminated locations in the region could be used as a testing ground. Her Rest of River website statement also says a goal of that investment, if secured, would be to produce “a cleanup over time that is less reliant and dredging, transporting, and disposing of sediment than the current permit calls for.” She couldn’t provide specifics of how that might unfold, but said the goal of the investment would be to “bring innovation here.”

The 2020 settlement agreement committed E.P.A. to “identifying opportunities to apply existing and potential future research resources to PCB treatment technologies,” but activists say the agency has not seriously considered processes they say have shown promise in both laboratory tests and projects outside the United States. E.P.A. has said it hasn’t seen evidence that any existing technologies could work either at scale or reasonable cost. But Jones and other environmental activists have sharply disagreed as they seek more thorough removal of PCBs from the river, floodplains, and any material eventually consolidated in the new landfill.

Tagliaferro, from E.P.A., said at a public forum last month that a current challenge-grant program seeks technology that will bring costs down to less than $100 per cubic yard, compared to the estimated $300 per cubic yard it costs to dredge and transport.

Facing up to hard votes, navigating recusals, and lessons learned

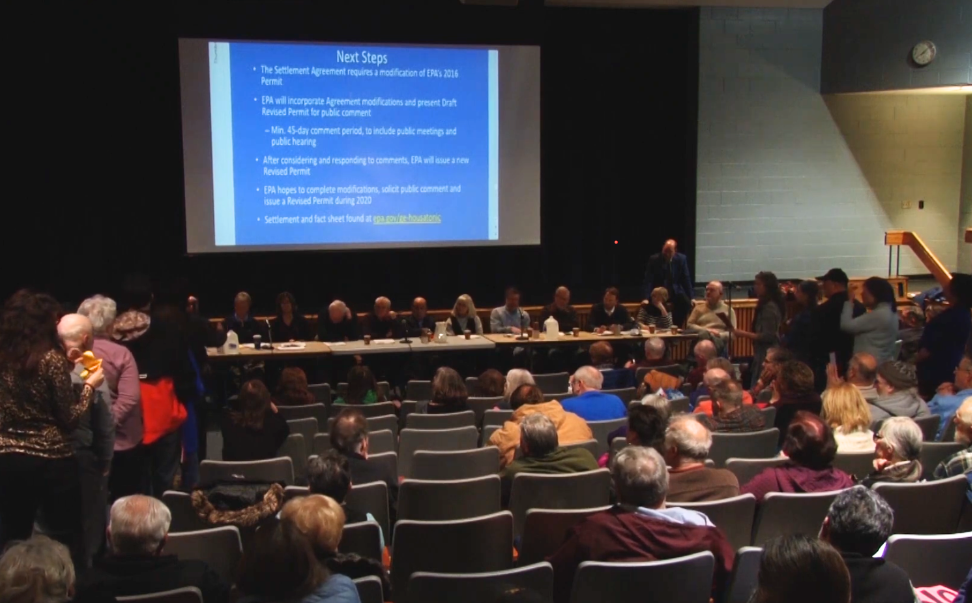

When the Rest of River agreement was announced on February 10, 2020, and a host of state and federal officials gathered in a crowded Lenox meeting room and touted it as a victory for everyone in the region, much of the initial local reaction was swift, loud, and angry. At the first public-information session held ten days later in Lee, Mitts, a number of Select Board members from the five towns, and E.P.A. officials sat at a long table in front of hundreds of residents, many waving “NO PCB DUMPS” signs. And for more than four hours, those who approved the agreement were berated by many of their constituents—often emotionally, and at times ferociously.

In the first public-information forum on the Rest of River agreement, residents lambasted their Select Board members. (CTSB-TV/YouTube)

At one point, Mitts made the same case about the process that led to the agreement as she does today. “Everybody who was a stakeholder, who participated in this remediation, everybody put their heart and soul in this,” she said. “Every one of these people lives here, everybody moved here for a reason. We love Berkshire County; we love this place. Everyone wants what’s best.”

Last week, I asked Mitts how she’d characterize her approach to Rest of River issues compared to Davis. After a pause, she replied, “Seventeen of us said yes to this agreement, and one person recused themselves.” (Lenox’s Neal Maxymillian also recused.)

Later, she declined to comment on the reasons for Davis’s recusal, but during our interview Mitts focused on leadership and decision-making. “I think if you’re given a position of leadership that you need to lead and you need to make tough decisions, and there are going to be times when there are difficult decisions to be made,” she said. “But that’s why you ran for the seat, and that’s what you’re elected to do, is to make those tough decisions.”

She put the vote on the settlement agreement into that category, conceding some don’t agree with her decision. “Yes, there are people who are going to say, ‘We don’t like the way that you’re leading on the Rest of River.’ Well, I think it’s important that we took that vote and we’re doing something to clean up this mess,” she said. “Being a leader doesn’t mean it’s easy. It means you’re doing work that needs to be done and making decisions and moving things forward for your community as a whole.”

When I asked Davis about her approach to recusals, like on Rest of River, she said, “If I have anything that could be seen as a conflict, I’m not going to participate. I try to abide by that as much as possible.” She said she’s particularly careful regarding any financial matters involving affordable housing due to her current employment at Construct.

State ethics guidelines require recused officials to not participate in discussions, votes, or any related official actions. They should leave the room or, at minimum, sit in the audience when the matter is being considered. If connected remotely, they should turn off their video camera.

But they can still speak in their personal capacity. A spokesperson for the commission pointed to its guidelines for Select Board members, which notes they “may still offer public comments on any matter in their personal capacity, as long as it’s clear they are not speaking or acting in their official capacity.”

Davis has done so on several occasions, though not always properly following the ethics guidelines. At Great Barrington’s 2023 and 2024 annual-town meetings, she spoke from the dais, alongside other Select Board members, on affordable-housing grants recommended by the town’s Community Preservation Committee, on which she sits as the Select Board’s representative. On that committee, she recuses from matters related to housing because of her employment with Construct, an organization that regularly applies for, and wins, grants from the town.

At the 2023 annual-town meeting, she spoke out against a controversial CPC grant recommendation for Alander Group, a local real-estate development company seeking $250,000 to underwrite two affordable units in the soon-to-be-renovated Mahaiwe Block, an historic building in downtown Great Barrington. She noted that she was recused from the matter at CPC, and that she worked for Construct, but didn't make clear that she was speaking in her personal capacity. After criticizing the developer’s part in clearing the building of low-income tenants, and detailing grant conditions she opposed, she said, to applause, "I think the money can be better spent, so I’m actually against this."

Those funds, along with $150,000 from a historic-restoration grant for Alander that was also defeated, went back to CPC to be awarded in subsequent grantmaking. A special CPC grant cycle was held a few months later; Construct applied for $92,400 for emergency-family housing, and during the proposal’s initial consideration, Davis recused and moved to the audience. Minutes later, she returned and participated in discussion of the next grant, a $150,000 request from Egremont real-estate developer Craig Barnum, also to underwrite affordable units in downtown Great Barrington. Davis asked how it was different than Alander's earlier proposal, and then voted against advancing the grant.

Later in that meeting, she announced that she should have recused from consideration of Barnum’s proposal. Ultimately, it was not advanced by CPC to the special-town meeting, but a revised version was recommended for a vote in May, 2024. At that time, Davis again spoke from the dais without making clear she was not acting in an official capacity, this time recommending the grant be approved, which it was.

In separate interviews this year, I asked Davis about those grants and recusals. During a conversation in February, she said she was “speaking as a citizen,” and agreed that she should not have participated or voted on Barnum’s initial proposal. Last week, she said, “As long as we say that we’re speaking as a citizen, from what I can see and what I’ve seen from my colleagues, that is the permitted way to speak.”

Last week, during a conversation on Rest of River, I asked Davis why she never chose to speak out on that issue in her personal capacity, as she has done at various times on affordable-housing matters from which she recuses from official action. She said that the housing matters were “an active vote, an active discussion that was happening at the time. I was in a position to say something, and that’s why I did at that point.”

Mitts has also erred in at least one instance by not strictly following ethics guidelines on participating in matters when recused. In early 2023, as the Lenox Select Board considered how to allocate $358,000 awarded through a landmark 2022 settlement with drug companies and distributors of opioids, she recused from participating because at the time she served as vice chair of the board of directors of The Brien Center, a large county-wide nonprofit that provides counseling services that include help with substance-use challenges. While she didn’t vote, she participated in the board’s discussions, including an extended board discussion in late March, 2023, when she suggested the town seek appropriate social-service agencies that can best use the funds, since the Town of Lenox didn’t have the staff or expertise to provide those services.

“I probably should have left the room,” she said last week. “Given the fact that I would not be voting on the funds, I probably shouldn't have said anything.” The board recommended those funds be granted to Rural Recovery Resources, a Great Barrington-based nonprofit.

The subject of difficult decisions faced by local officials also came up early last year in Great Barrington. Davis was sharply criticized for abstaining from a vote on a contentious, long-running issue: Whether to grant the town’s last remaining retail beer-and-wine license to Price Chopper, a grocery-store chain that’s had a location in Great Barrington for decades. The company, which has 130 locations across six New England and mid-Atlantic states, was eager to overhaul and expand its local store—which employs more than seventy people—to better compete with grocery stores nearby. That includes a Big Y location on the other side of town that was awarded a similar license by the Select Board in 2018.

Price Chopper had come before the Select Board once before, in May, 2022; at that time, Davis voted to grant the license, but it didn’t win enough votes. When the company returned to try again, local liquor-store merchants and small-business advocates again rallied hard against it during an intense, two-and-a-half-hour public hearing. As the Select Board debated, Davis said she was torn, calling it “a tough one.”

When a vote was called, Davis abstained. She faced immediate blowback in the community for skipping the tough vote, and two weeks later, in a letter-to-the-editor of The Edge and the Eagle, she apologized. “As an elected official, my job is to represent the interests of my constituents and make decisions on their behalf. In this instance, I did not meet that responsibility,” she wrote, promising to “embrace the lessons learned.”

Last December, when the matter came before the board for a third time, she voted in favor and the license was granted. Before the vote, she apologized again and said she regretted the earlier abstention, while noting that her vote at the earlier meeting wouldn’t have changed the outcome. But now, she said, casting a vote was an example of applying what she learned.

A 2024 campaign foreshadowed at a 2018 Rest of River forum

At a Rest of River-related event that foreshadowed the political competition to come six years later, Mitts, Davis, and White all spoke within minutes of each other at a public-input forum held in December, 2018.

At the time, Davis worked for Eagle Mill Redevelopment and its project next to the Housatonic River in Lee. She would be elected to Great Barrington’s Select Board the following May. At the session, she suggested that G.E. see the money it would spend to ship all PCB-tainted materials out-of-state as “a $250 million PR campaign,” and appealed to the company to “show they actually care about the environment, that they can actually make this negative that they’ve caused in this community into a positive.”

Marybeth Mitts, Leigh Davis, and Patrick White—all of whom would become candidates for state rep in 2024—speak at a forum on Rest of River in December, 2018. (CTSB-TV/YouTube)

Mitts, still months away from her own election to the Lenox Select Board, highlighted costs borne by other communities during large environmental remediations and called for payment to the affected towns—something that became part of the settlement agreement. “There’s got to be some remuneration to the places that have been contaminated, and I hope that’s taken into consideration during mediation,” she said.

And White suggested moving the process along and focusing on the jobs that might be created by the remediation project. “There’s entire generations of young people who are not deciding to stay here in the Berkshires because they can’t find good work,” he said. “Getting going on this cleanup, even if it’s a compromise, might help a lot of these people find good jobs.”

A public uproar over plans for PCB transport mobilizes residents, activists, and soon-to-be candidates

As an elected official, Davis’s first widely reported engagement on Rest of River came last November, when she joined the chorus of residents at a public forum who criticized G.E.’s initial transportation plan—and a presentation that many said was lacking. In comments that one news account described as “blistering,” she said the proposal failed to fully evaluate the use of rail to transport PCB-laden material, instead of trucks, and dinged the company for providing attendees with inadequate details of truck routes through their communities. “We did not see any real attempt to explain the availability and feasibility of using railroad,” she said, calling the omissions from GE’s presentation “an insult to those gathered here.”

At a November, 2023, public forum in Lee, Davis excoriated G.E. for plans to rely primarily on trucks to move PCB-tainted materials to the landfill and out-of-state. (CTSB-TV/YouTube)

Input like that at public forums and in written comments had a substantial impact. Even before E.P.A. issued its formal response to G.E., in June, the agency made clear that the company needed to perform a new evaluation of rail transport and hydraulic pumping to reduce the use of trucking. And the new plan submitted by G.E. last month proposed a remarkable seventy-six-percent reduction in the estimated number of round-trip truck trips—which at one point were estimated at more than 55,000 transits, or nearly fifty per day, over the coming decade. It also said it would use hydraulic pumping in locations it previously claimed were inappropriate. The new plan was an achievement widely attributed to strong public reaction, grassroots organizing, and the detailed, often-strongly-worded formal comments submitted by local Select Boards, including those in Lee, Great Barrington, and Lenox.

Mitts and Davis both cheered the revised plan, which has now entered another public-comment period. Mitts told me the reduction in truck trips is “a huge win for all the towns, and we are very proud of the fact that we’ve been advocating for that since the first transportation plan [was issued.]” She called it “the most effective transportation plan we could have hoped for.” Davis called the new plan is “a big win” and said she’ll “continue chipping away at the second transportation plan and the quality-of-life compliance plan and making sure that the impact is not as large as it started off as.”

Mitts again pointed to the settlement agreement, and said the substantial improvement was only possible because of the work done to craft and approve it: It mandates detailed transportation and quality-of-life plans along with requirements for substantial public input and review. “Frankly, we lobbied very heavily to be in this [process] so that we could have an impact,” she said, “so this cleanup wouldn’t be done to us the way the pollution was done to us.”

The prospect of trucks hauling PCBs through communities dozens of times per day—covered and properly secured, regulators say, and therefore not putting residents at risk from transient airborne PCBs—to and from the Lee facility for more than a decade was among the issues Jones and others had been warning the other towns about for years. But it got little attention until last fall, when the initial plan was submitted. Jones said it was among the reasons his board began requesting, in the spring of 2023, a meeting of all five Select Boards to discuss Lee’s concerns about Rest of River. But the boards in Sheffield, Great Barrington, Stockbridge, and Lenox all declined.

Last week Jones said the new transportation plan is an example of why his board has sought that collaboration and dialogue. “When select boards come together and take a strong stand on something like trucks versus trains, all of a sudden it’s a whole different conversation,” he said. “And I think that’s what happened. We said over a year ago, or two years ago, that the pushback isn’t going to start to take off until people realize this stuff is going to be driven through their streets and in front of their homes.”

From his perspective, that level of strong community reaction was not fully anticipated by those who voted for the agreement. “A lot of them, like the Great Barrington board, don’t want to talk about it,” he said. “It’s hard to get it on their agenda because I think they know they made a mistake.”

That resistance was among the reasons Jones endorsed Patrick White in the Democratic primary. He specifically pointed to White’s advocacy for that all-boards collaboration. “Patrick White was the only select board member in all four of those towns who advocated for an open-meeting discussion to address the ongoing problems with the [Rest of River] plan,” Jones wrote in his endorsement. “Patrick stood alone in his quest to bring the facts to [residents].”

Asked about Rest of River during the Eagle’s general-election debate on October 8, Davis hinted at support for that kind of collaboration. “This is something that Lee cannot shoulder by itself, and the rest of the towns need to be behind it,” she said.

When I asked why she hasn’t used her perch as vice chair of the Great Barrington Select Board to press for that public, five-Select-Boards meeting—her employment and consulting work for Eagle Mill Redevelopment, which she said was the basis for her recusal, concluded in May, 2021, according to her LinkedIn profile—she demurred. “You have to remember that I’m not the chair of the Select Board,” she said. “The chair makes the decisions on what is on the agenda and what is not. So, you’d have to ask Steve Bannon.” (Bannon, the board chair since 2018, did not respond to an email seeking comment.)

Davis said she’s been working on Rest of River through conversations with Jones, representatives of the Housatonic Railroad Company, and the head of the local board of health. She also pointed to her attendance at several meetings of Lee’s PCB Advisory Committee—“I don’t think I’ve seen Marybeth there,” she said about her approach versus her opponent’s. (Mitts responded via email that she hasn’t attended meetings of the group, citing in a one case a scheduling conflict with a meeting of the Berkshire Farm Bureau. She wrote that she is “in the midst of reading the most recent transportation and disposal plan.”)

Mitts didn’t answer directly when asked if she supports a public meeting and the type of ongoing, all-boards collaboration Lee has sought. In an email, she told me that she hasn’t discussed it with her Select Board colleagues, and that because of Maxymillian’s recusal, it would require some logistics to put it on an agenda. She also wrote, “We have three of the four people on the board currently who voted for the 2020 agreement, so that’s another consideration.”

A swirl of endorsements, and a debate about what they mean

A debate around the process and meaning of endorsements became part of the campaign in mid-summer, as Davis notched an impressive number of them from a range of progressive politicians and advocacy groups. In mid-October, Mitts picked up an endorsement from the Berkshire Eagle’s editorial board.

Whether candidate endorsements from politicians, celebrities, advocacy groups, or newspapers impact voter behavior is a hotly debated topic and a subject long examined by political scientists. But not always with helpful conclusions: One 2016 survey of the literature suggested “studies show that while endorsements sometimes help citizens to make political decisions that reflect their preferences, they may also lead citizens astray or have no effect on their decisions.”

Despite his popularity in Lee, where Jones won a crushing victory over the former Select Board chair in 2021 and ran unopposed this year, his endorsement wasn’t enough to help lift White to victory in the Democratic primary or even in Lee: Davis carried the town with 421 votes to White’s 279, with Minacci third with sixty-four.

A few weeks ago, Jones endorsed Davis in advance of the November 5th general election. He told me that with White’s “chess piece off the board,” and after a number of conversations with Davis, he believes she has “broadened her understanding” of Rest of River issues. He said he likes Mitts “very, very much,” but said she “is still of the opinion that this is the best deal we’re going to get. I’m sure I could work with her on a number of issues, but this is one where it’s a fundamental difference of opinion.”

The Eagle’s endorsement of Mitts highlighted both candidates’ “record of real public service as well as relevant professional experience,” but said it chose Mitts for “a critical edge in the sheer volume and density of public sector work experience needed to legislate effectively.”

The paper’s endorsement came alongside a news story describing her meeting with the editorial board. On Rest of River, she was asked if it was the responsibility of the district’s state representative to “speak truth to the grassroots”—in this case, pushing back against the environmental and community activists who have been fighting the settlement agreement and a local dump for nearly five years—and other elements of the Housatonic River remediation project for decades. She replied, “Absolutely. I tell them this is happening.”

It was not a surprising question: The Eagle’s editorial board has often criticized the activists fighting the terms and implementation of the settlement agreement and the siting of a new landfill. Last week, in an editorial that gave credit to a “strong grassroots effort” for substantial changes to the project’s transportation plan, it again hinted at that view, writing that the improvements came “not through reflexive opposition in search of impossible perfection that pleases everyone but by proactively advocating for a plan that takes into account impacted residents’ quality of life.”

Asked about her exchange with the Eagle’s board, Mitts told me that she wants to make sure all residents are heard. “And to give them the opportunity to continue to discuss their fears and frustrations and their concerns, and try to respond to them with facts, and show how being involved in this process, and having a way to leverage our concerns, is more important than having the process done to us.”

She again pointed to the negotiated terms of the settlement agreement and described what she feared if it had not been approved by the Select Boards of the five towns. “G.E. could have just said, ‘This is what we’re doing, and the towns, we really don’t want to hear from you people, this is the way we’re going to clean it up, and there’s going to be 100,000 truck trips, and that’s how it’s going to happen.’ We got a better deal than that,” she said.

Like any candidate, Davis has trumpeted her many endorsements in press releases, social-media posts, and during this year’s candidate forums. She received endorsements from environmental organizations including the Massachusetts chapter of The Sierra Club, climate activists at 350Mass Action, the Environmental League of Massachusetts (ELM) Action, and Clean Water Action, a national grassroots advocacy organization with a state chapter in Massachusetts.

At the Eagle debate last month, Davis defended her broad range of endorsements as ratification of her campaign proposals and work in local government, and said very little of her campaign funds came from organizations that endorsed her. She also described how she won the endorsements, saying, “They put us through a very intense process of questionnaires, and panel interviews, and really vetting us.”

To learn more about the environmental organizations’ endorsements, and if the groups took positions on Rest of River, I reached out to Sierra Club, ELM-Action, and Clean Water Action. The Massachusetts chapter of Sierra Club didn’t respond, but when I spoke to Casey Bowers, executive director of ELM-Action, she described their endorsement process as a combination of candidate questionnaires, internal staff discussions, and a final vote by the group’s board of directors. She said the organization’s policy focus includes the intersection of the environment with transportation and housing, which she said were issues Davis has made a priority.

On Rest of River, she said the group has not been directly involved in matters related to the Housatonic River. “We’ve watched, because obviously it’s a critical river, but we tend not to get involved in more site-specific issues,” Bowers said, explaining that ELM focuses on statewide issues and legislation. The group’s endorsement was based on “our interactions with [Davis] and some of the answers that we saw, as well as what she’s been saying publicly around climate and the environment,” she said.

Bowers said that several, but not all, Third Berkshire candidates participated in its process, which included candidate questionnaires that she declined to share, citing a confidential-endorsement process.

Indeed, while some advocacy groups that endorsed Davis in the race, like Progressive Mass, are forthcoming and public about their endorsement process, others are less so. In a press release about the Clean Water Action endorsement, Davis wrote, “Clean Water Action is a national environmental leader focused on actionable solutions, and their endorsement is particularly meaningful to me. I am deeply honored to be recognized for my advocacy in this area following a rigorous and competitive candidate screening process.”

When I contacted Clean Water Action to learn its position on Rest of River, details of its endorsement process, and what it asks on candidate questionnaires, the group’s spokesperson scheduled an interview with the Massachusetts chapter’s co-executive director. But the interview was canceled shortly after I sent those topics for discussion. The spokesperson declined to make anyone available or provide answers to submitted questions, citing “staff vacations.”

Mitts, White, and Minacci all told me they did not participate in Clean Water Action’s endorsement process, and none recalled any opportunity to submit questionnaires or sit for candidate interviews with the group. Last week, White wrote in an e-mail, “Had I known about them, I would have had a lot to say about the work I have done for Rest of River and Housatonic Water Works,” referring to the troubled private water company that services part of Great Barrington and a small number of customers in nearby towns.

Davis declined to provide copies of answers she submitted for various endorsement questionnaires, including Clean Water Action, and said the endorsing organizations’ questionnaires are confidential. (At least one group that endorsed Davis, Progressive Mass, posts all candidate questionnaires online, including those completed by Davis and White. The group noted that Minacci and Mitts did not submit questionnaires.)

Mitts also declined to provide copies of her candidate questionnaires; she said she typically submitted them via online forms and didn’t retain copies.

The post-election road ahead on Rest of River

How would Davis and Mitts approach ongoing Rest of River developments if sent to Beacon Hill? Mitts said she’ll focus on ensuring that river-corridor communities don’t face any unexpected expenses. “I’m going to stay in this, because it’s important that the towns don’t get saddled with additional costs moving forward,” she said. “If there’s something unforeseen, ‘we found a greater concentration [of PCBs] in Stockbridge, or a greater concentration in Great Barrington or Sheffield,’ and they were only allotted $1.5 million in the consent decree, and it costs them more to cope with this, or they had other costs, I would make sure that those towns did not have to bear those costs.”

Davis said that her work on the issue won’t depend on the outcome of the election. “I’m going to be actively involved,” she said, “as someone that wants to be a part of the coalition ensuring that the consent decree is followed, and that there’s a quality-of-life compliance plan, and the transportation plan is the best case for residents.” She said she also wants to be sure Lee has the resources to pay for things like independent testing as the project proceeds.

She also vowed to stay the course over the life of the project, regardless of where she sits. “I’m going to be doing this no matter what title I have,” she said. “Even though it’s going to be thirteen years of this, I’m going to be following this and trying to advocate as much as I can.”

Indeed, as she’s campaigned, Davis has not only attended meetings of Lee’s PCB Advisory Board, but has made other appearances connected to Rest of River. Last month she attended an E.P.A.-hosted forum on risks from airborne PCBs, asking about plans for air testing during the project and if substantial cuts to the E.P.A. budget after the election could mean the remediation project might run out of money. E.P.A. officials replied that a change in administration will have no impact on G.E.’s responsibility to fund the work.

Davis attended an E.P.A.-hosted meeting in Lee last month, asking questions about air sampling and who will fund remediation if E.P.A.'s budget is cut. (CTSB-TV/YouTube)

Tim Gray, an environmental activist from Lee, who, since the 1970s, has been battling for a full cleanup of the river as head of the Housatonic River Initiative, is skeptical that a new state representative will stand with those residents who want a vastly more substantial river cleanup. In the past, he said, there hasn’t been robust support from the region’s state and federal elected officials. “My group, at least, we’re all disappointed in them because they really didn’t participate. They really didn’t help us do anything,” he said, suggesting they “only showed up” after the settlement agreement was signed.

(HRI was initially a party to the mediation process but opposed the settlement agreement, did not sign, and was among the groups that pursued legal action to overturn it.)

Tim Gray, from the Housatonic River Initiative, leads an information session not long after the settlement agreement was released in early 2020. (Terry Cowgill/YouTube)

Pignatelli has long championed the deal and has described it as “historic.” At the February, 2020, event in Lenox to announce the agreement, standing alongside a who’s who of state and federal officeholders, he said, “This agreement is bigger than all of us. It’s about creating a better Berkshires for the next generation.” Last winter, as public anger about plans for trucks rolling through communities hit a fever pitch, Pignatelli and the region’s state senator, Paul Mark, sent a joint letter to E.P.A. calling for increased use of rail transportation “in all situations where it is technically feasible and safe to do so.”

(Pignatelli did not respond to an email seeking comment on the role the district’s next representative should play in Rest of River.)

Gray’s skepticism is evident in how little attention he’s paid to election-year politics: When I first asked him about the race a couple of weeks ago, and what he expected from Mitts or Davis, he conceded he didn’t know who was running. “It’s not much on my radar,” he said. In an interview a few days later, he said, “They’re speaking out now because it’s all about brownie points, as far as I’m concerned. It’s all about making them look good.”

As it stands, Gray doesn’t expect the thirteen-year-long project will, in the end, fare any differently than years of work to remediate PCB contamination in forty miles of the Hudson River—also dumped there by G.E. “The [Housatonic] is massively polluted, and the cleanup is going to go the same route as the Hudson River,” he said.

The results of that project—described by E.P.A. as a Superfund success story—have been challenged by environmental groups who cite independent reports they say suggest E.P.A.’s own data show targets for PCB reduction have not been met. They are pressing the agency to confirm the outcome is “not protective of human health and the environment.” E.P.A. said in July that it is collecting more data on PCBs in the Hudson to better evaluate the six-year, $1.7 billion cleanup, which removed 2.75 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment and ended in 2015. The agency said that process will take “a few years.”

Meanwhile, as the race between Mitts and Davis heads to its conclusion, Gray’s work alongside other local activists continues: As reported by Leslee Bassman at The Berkshire Edge, HRI was among four regional groups that have asked E.P.A. to perform updated risk assessments and sampling of PCB concentrations in the Housatonic to, among other things, ensure the settlement’s requirement to locate only less-contaminated material in the Lee landfill is met. “Should this investigation result in an identification of more toxicity in Rest of River,” the groups wrote, “a re-evaluation of the UDF and removal levels must be considered.”

There’s been no public polling in the race, so it’s unknown where voters stand on Davis versus Mitts. Bowers, from ELM-Action, told me that her organization doesn’t endorse in every contested state-representative election, but decided to get involved in the Third Berkshire contest because of how competitive it is. “I think this is going to be a tight race, where both candidates are quite talented. So, we look forward to seeing what happens.”

Correction: An update was made on November 4, 2024, to reflect that Mitts was vice chair of The Brien Center, not chair, when the Lenox Select Board discussed opioid-settlement funds in 2023, and to include her e-mail response regarding attendance at meetings of Lee’s PCB Advisory Committee.