A few questions remain, but the airport now has some legal protection against neighbors' complaints that it has sought since 2017.

∎ ∎ ∎

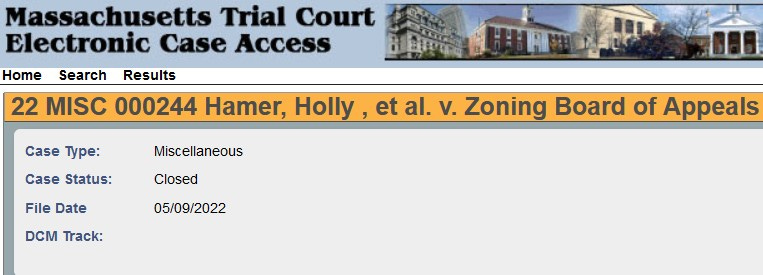

The plaintiffs in the Land Court zoning-enforcement case against the Town of Great Barrington and Berkshire Aviation Enterprises (BAE)—the owner and operator of the town’s privately owned airport which last fall petitioned to be added as a defendant—filed paperwork yesterday to dismiss the case, which is now closed, according to the case docket.

In the fall of 2021, airport neighbors Holly Hamer, Marc Fasteau, Anne Fredericks, and a dozen-and-a-half nearby residents asked the town’s building inspector, Ed May, to limit the airport’s operations, based on its status as a preexisting nonconforming use dating to the early 1930s. He refused, as did the town’s Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA). The Land Court appeal, filed just over a year ago, ultimately forced the airport to, once again, appear in front of the town’s Selectboard seeking the special permit needed to operate an aviation field in the R4 residential/agricultural zone—and to do so unrestrained by its longstanding zoning status.

A well-organized “save the airport” campaign rallied the community against the neighbors and their complaints about noise, activity level, safety, and environmental risks—expressed in testimony to the board since at least 2017—and in support of what they argued is a beloved, integral part of Great Barrington and its history. The airport’s attorneys suggested that without a special permit, the airport’s “existence” was at stake, while also successfully pushing back against efforts to establish clarity around the level of activity at the airport, which has been a central issue for many years. (An Argus data analysis found that operations at the airport have more than doubled in the last few years, driven largely by increased flight-school activity.)

With thousands of online- and paper-petition signatures, a social-media campaign by advocates that sometimes directed substantial anger and vitriol at airport neighbors, and by packing the Selectboard hearing room for each of the four public meetings on the permit, significant pressure was put on the board to reverse 2020’s unanimous rejection of the aviation-field permit.

The Selectboard’s 4-1 vote to approve the permit included conditions it suggested will address both neighbors’ complaints and bylaw language mandating that aviation operations not be “objectionable”—the latter a requirement contested by the airport’s attorneys as inapplicable due to state and federal preemption. The conditions also include modest limits on the hours of “continuous takeoff-and-landing” practice, but not more generally on the flight school, other than a prohibition on lessons on July 4th and Memorial Day. (There was little activity of any kind at the airport on Memorial Day, according to flight-tracking site FlightAware.com.)

Conditions also require the airport to provide informational reports to the town each year describing its operations and activities. Though it’s unclear what, if any, action the town can or will take based on those reports, including enforcement of a limit placed on the airport’s aircraft-maintenance business at an undefined “current” level. The permit’s conditions also approve the level of flight operations “as is,” though that level was also not clearly defined. Opponents of the special permit, including now-former Selectboard member Ed Abrahams, argued that such conditions are both insufficient and unenforceable.

The permit’s aviation-related restrictions must also still be approved by the Aeronautics Division of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) before they can become effective. A denial by MassDOT would invalidate the special permit.

A few outstanding questions include whether the airport—now a conforming use—complies with the town’s groundwater-protection bylaw. Those provisions, adopted in 2006, restrict activities above the town’s aquifer and in other sensitive locations near bodies of water, including limiting the amount of waste oil produced in the airport’s maintenance business to no more than 27 gallons per month, regardless of how or when it disposes of it.

That bylaw section also requires a separate special permit to allow use of hazardous and toxic materials beyond levels of “household use,” something that remains a source of concern for neighbors and others who have questioned risks from aircraft maintenance and the wisdom of allowing the airport to store 20,000 gallons of aviation fuel in an underground-storage tank above a key drinking-water supply. That tank, installed in 2018, is a double-walled, fiberglass, alarmed tank widely considered the industry standard. There was no evidence of prior leaks from two single-walled steel tanks that were removed in 2017.

For her part, Fredericks, who has lived on Seekonk Cross Road since 1991 and has spoken at a host of airport-related hearings since 2017, told me today that the outcome raises concerns about what it may mean for others in town. “All of the people who signed the letter to the building inspector [in 2021], and the people willing to put their names on the Land Court action, were really looking for the town to defend their bylaws,” she said. “That was the whole crux of the situation. The bylaws are potentially meaningless if the Select Board, whose job it is to enforce the bylaws, chooses not to do it. Anything can happen,” she said.

She said that means that others, in various neighborhoods, should be worried. “It means that neighborhoods are not safe. Why would you make an investment in Great Barrington if you don’t know that the bylaws will be supported and enforced?”

With a special permit in hand and no danger of an adverse Land Court decision, the airport now has the protection it has long sought from legal and zoning complaints that its owners, longtime pilots, and airport advocates have said was inappropriate “harassment”—a term also used by at least two ZBA members as it considered the matter in the spring of 2022.

Rick Solan, the retired American Airlines pilot who is majority owner of BAE, told me in March that he knows his operation will be watched even more closely now. He said he aims to comply in full with the special-permit’s conditions. “I have my word,” he told me, insisting the community can trust him. “Right now I'm gonna be under a microscope. I’m going to be under a big microscope. So do you think I'm going to even come close to testing the waters on that? No. I'm going to go above and beyond,” he said.

The airport’s first informational report on its 2023 operations is due to be filed with Town Manager Mark Pruhenski next February.

∎ ∎ ∎