Organizations that protect journalists here and abroad are concerned about Trump's attacks on the press as he prepares to take office again. Labeling reporters "the enemy of the people" also recalls specific threats made against Massachusetts journalists in 2018.

∎ ∎ ∎

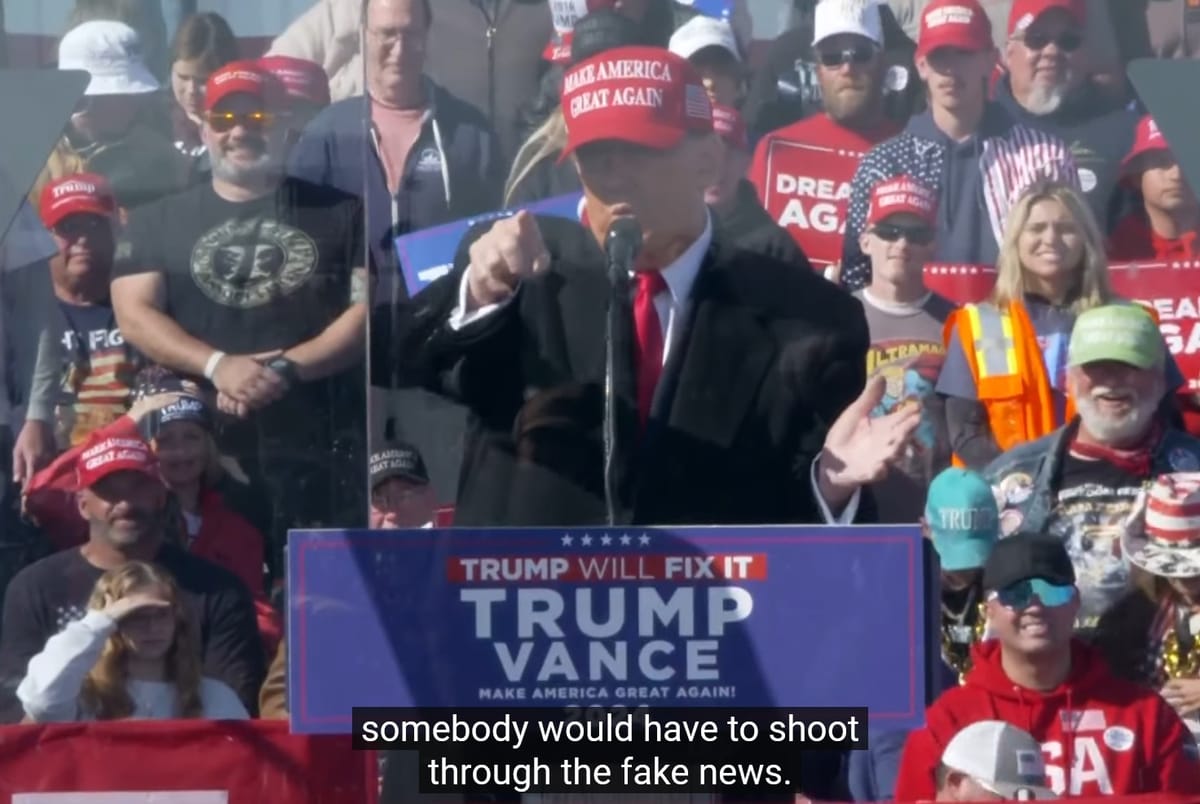

At a campaign rally in Pennsylvania two days before the 2024 general election, President-elect Donald Trump said he would have few concerns if journalists covering his campaign were shot.

“To get me, somebody would have to shoot through the fake news,” he said, looking through the bullet-proof glass surrounding him and gesturing toward the reporters at the event. “And I don’t mind that so much, I don’t mind, I don’t mind that,” he said. The crowd laughed and cheered.

Trump’s statement garnered headlines but quickly disappeared into the loud, pre-election din—recall the diversionary power of “they’re eating the dogs, the people that came in, they’re eating the cats”—and the seemingly seconds-long news cycle of the Trump era. It blended into an uncountable number of attacks on reporters and the media that have been part of Trump events, press conferences, and social-media posts for much of the last decade.

Since at least February 17, 2017, he has also regularly called the press “the enemy of the people”—a phrase used by autocrats and dictators in darker times—as he regularly suggests imprisoning journalists, revoking broadcast licenses, and rolling back long-settled law that provides for press freedom and the free flow of information that’s vital for popular democracy. (Five days later, the Washington Post adopted the slogan, “Democracy Dies in Darkness.”)

The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 17, 2017

By now, as Trump readies a new government that will take power on January 20, 2025, Americans understand all this as deliberate strategy at the core of his politics. Indeed, during his 2016 campaign, he told CBS journalist Leslie Stahl that his goal was to undermine trust in the news media, “so when you write negative stories about me, no one will believe you,” she said he told her.

With controversial choices of loyalists for top positions at the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Justice Department, his escalating rhetoric also recalls a specific incident here in Massachusetts during his first term as president.

In August, 2018, the Boston Globe organized more than 300 news outlets across the country to simultaneously publish editorials about the growing threat to press freedom posed by the president’s attacks on reporters and media outlets. It felt compelled to do so, the paper’s editorial board wrote, because “journalists are not classified [by Trump] as fellow Americans, but rather ‘the enemy of the people.’ This relentless assault on the free press has dangerous consequences.”

Locally, The Berkshire Eagle’s editorial that day said, “Mr. Trump’s behavior has placed the American experiment in democracy in unprecedentedly perilous times, and a free press has become more central to our nation’s survival than ever." It argued that “for the sake of a republic already riven with discord, these attacks must be met with appropriate resistance at every opportunity.”

Trump responded to the Globe-led effort with a series of messages on the-platform-formerly-known-as-Twitter, including one that read, “There is nothing that I would want more for our Country than true FREEDOM OF THE PRESS. The fact is that the Press is FREE to write and say anything it wants, but much of what it says is FAKE NEWS, pushing a political agenda or just plain trying to hurt people. HONESTY WINS!”

His “honesty wins” comment came midway through a presidential term that the Washington Post would later report, in January 2021, featured more than thirty thousand “false or misleading” public statements made by the forty-fifth president. The Post exhaustively detailed each one in a database; it was a remarkable example of vital and important journalism.

Video clip of Trump saying he "doesn't mind much" if journalists are shot. (Via YouTube/Washington Post)

The lies and misstatements have continued in a torrent, often ignored or explained away by his supporters as jokes, mere entertainment, or “Trump being Trump.” And they come so fast and furious that journalists can't easily keep up, as in evidence at the president-elect’s odd, stream-of-consciousness press conference yesterday at Mar-a-Lago.

Politicians of all stripes have long had their own creative interpretations of facts and reality (understatement heavy) along with routine unhappiness with press coverage. But a communications strategy of denying truth and flooding the zone with misrepresentations—while attacking the media—has now been fully embraced by ambitious Trump allies. One notable example: The vice president-elect, Senator J.D. Vance of Ohio, admitted that claims that Haitian immigrants in an Ohio town were stealing and eating pets were baseless but said it was politically useful to “create stories.”

Back to Massachusetts in 2018: As soon as the Globe announced its simultaneous-editorial project, a California man began making threatening calls to the paper’s newsroom. “You’re the enemy of the people,” he said, using Trump’s oft-repeated phrase, “and we’re going to kill every fucking one of you.” In one of more than a dozen calls, he threatened to shoot Boston Globe employees in the head “later today, at four o’clock.” In response, police were stationed outside the Globe’s office building.

Two weeks later, the man was arrested in California and prosecuted by the U.S. attorney in Massachusetts—who had been appointed by Trump. FBI agents found nineteen firearms at his home. He later pleaded guilty to seven criminal counts of making threatening communications across state lines. He was imprisoned for four months.

At his sentencing, he apologized. “Making those phone calls was the worst decision I’ve ever made. I really can’t believe I said those things. I just hope that those … people can forgive me,” he said.

The criminal-justice system and legal processes worked as designed. He was held accountable and appeared remorseful for his actions. The U.S. attorney, Andrew Lelling, said, “Anyone—regardless of political affiliation—who puts others in fear for their lives will be prosecuted by this office.”

With the president-elect’s recent statements about reporters—”I don’t mind” if they’re shot—and his campaign pledges to seek “retribution” and perhaps take a direct role in Justice Department prosecution decisions, will threats of violence against journalists over the next four years receive the same attention from federal law-enforcement agencies and Trump-appointed prosecutors? Or will such threats be overlooked?

That concern became more pronounced when Trump nominated Kash Patel to head the FBI. In recent weeks, news coverage has shined light on Patel’s longstanding disdain for the media—and his explicit plans to target reporters. “We’re going to come after the people in the media … whether it’s criminally or civilly, we’ll figure that out,” he said on the podcast of Trump advisor Steve Bannon. (Note to Great Barrington-area readers: That Steve Bannon is not this Steve Bannon.)

Support The Argus's independent journalism in 2025.

Make a tax-deductible contribution today.

Become a contributing memberIn February, 2024, Patel told attendees at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference, “We [have to] collectively join forces to take on the most powerful enemy that the United States has ever seen,” he said. “And no, it’s not Washington, D.C. It’s the mainstream media and these people out there in the fake news. That is our mission.”

All of this has attracted attention beyond newsrooms. In an NPR story about Patel’s links to conspiracy theorists, a former Patel colleague, Charles Kupperman, who served as a deputy national security advisor during Trump’s first term, warned that “[Patel] will carry out any orders that the president gives him, and he will have an opportunity, if he is confirmed at the FBI, to invoke retribution against individuals.”

A Trump transition spokesperson dismissed that analysis, telling NBC News last month that “the FBI will target crime, not individuals, with Kash leading the bureau.”

But a host of organizations that protect journalists here and abroad are clearly concerned. The Committee to Protect Journalists highlighted the rise in threats—and worse—against journalists in recent years. “Legal persecution, imprisonment, physical violence, and even killings have sadly become familiar threats for journalists across the world. They must not now also become commonplace in the United States, where threats of violence and online harassment have in recent years become routine,” the group wrote the day after the election.

Reporters Without Borders recently called Trump’s return to power “a dangerous moment for American journalism and global press freedom.” The organization had warned in late October that a troubling complacency may be setting in: “[We are] deeply concerned that American media—and in turn, the wider public—may be growing numb to the existential threat Trump’s attacks pose to American press freedom,” it wrote.

“We’re going to come after the people in the media … whether it’s criminally or civilly, we’ll figure that out.”

--Kash Patel, FBI director nominee

And earlier last year, the International Women’s Media Foundation surveyed more than six hundred U.S.-based journalists and found thirty-six percent “reported being threatened with or experiencing physical violence while working as a journalist.” Almost a third had been threatened with legal action, and a third faced online harassment.

Trump’s allies and campaign spokespeople have dismissed these concerns—even as they have continued their own verbal and social-media assaults on reporters and media organizations whenever reported facts are inconvenient or stories unfavorable.

At this uncertain moment, it’s worth recalling some wise words about the necessary relationship between government officials and the journalists that cover them.

The late U.S. District Judge Murray Gurfein, who ruled forty-five years ago last month that the federal government could not block publication of documents revealing government lies about the Vietnam War, summed it up well in that landmark “Pentagon Papers” decision: “A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, an ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.”

It’s clear that the president-elect has no desire to be one of “those in authority” willing to suffer that kind of press.

Emboldened by a remarkable political comeback and return to office just four years after a violent insurrection sought to keep him in power, and now busy installing hardcore loyalists like Patel—a man who promises to go after journalists and whose memoir includes a list of government officials he says should be targeted, prosecuted, and jailed—it remains to be seen what will come of truth, facts, due process, press freedom, and the core democratic processes that rely on them.

But we’re about to find out.

∎ ∎ ∎

"Noted" is a forum for informed comment, analysis, and reported columns.

Have thoughts? Submit a letter to the editor.