Another small-town Select Board votes to end hybrid in-person-and-remote participation for its meetings. Two members didn't like a question about their decision.

∎ ∎ ∎

It’s not always easy to be an elected or municipal official in our small Berkshire County communities.

Problems are increasingly complex and expensive to solve. Feedback from constituents, both in person and online, does not always model respectful engagement. (Understatement very heavy.) Volunteer boards that oversee zoning, environmental protection, public health, and historic preservation struggle to fill all positions—which increases the workload for those who remain. Municipal-staffing challenges mean administrative roles in small towns can go unfilled, leaving important work incomplete and vital projects deferred.

And, of course, pesky journalists like me hang around to ask impertinent questions, rummage through public records, and otherwise make a nuisance of ourselves. (For good reason, and without fear or favor, naturally.)

But engaging more people in local affairs as observers, informed voters, participants, and ultimately as volunteers and elected officials can only be to the good.

All of this is prelude to evaluating the Town of Alford Select Board’s decision this week to end its hybrid in-person-and-remote meetings, and going forward, only hold in-person sessions. It wasn’t just the board’s two-to-one vote that leaves a sour taste, but also the vague arguments and near-angry tone of board members defending their vote.

(Disclosure: I’ve lived in Alford, a town of fewer than 500 residents, since 2008. In 2015, I ran a brief, 72-hour, unsuccessful write-in campaign for Select Board that focused, in part, on government transparency.)

When the pandemic turned the word “Zoom” into something more than the name of a campy 1970s children’s show, engagement with local government was possible in new ways. The impact has been positive: Flexibility for board members to connect from far-flung locations, and the opportunity for the public to more easily participate while juggling jobs, kids, and life. It also allowed journalists—struggling in a media landscape littered with shuttered news outlets, tight budgets, and staff cuts—to cover more public meetings and provide useful information to their communities.

Engagement over Zoom is not perfect. There’s something about getting the sense of the room in a public meeting—and seeing who else is there—that’s not always possible online. Still, it should almost go without saying that lowering, not raising, the bar for public participation should be a priority of those elected to serve that public.

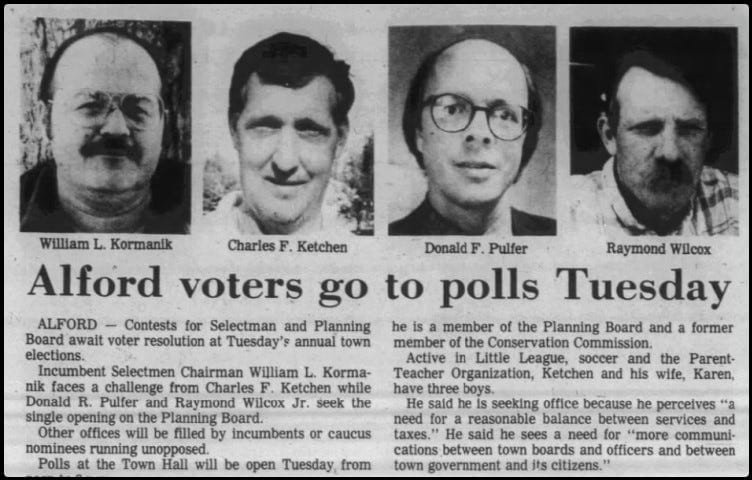

But two members of Alford’s three-person board went the other way. Chair Charles Ketchen—who has been a member of the Select Board for a remarkable 36 years—and Peggy Rae Henden-Wilson, who is also employed as Alford’s appointed-and-paid town clerk, voted to end remote participation. Peter Puciloski, a local land-use attorney first elected in 2019, preferred keeping it. He noted that while it’s not required, he favors it. “I think it’s a good idea,” he said.

Henden-Wilson, who in 2018 became the first woman ever elected to the town’s Select Board, had a different view. “I would prefer to stop hybrid meetings and meet in person,” she said after introducing the motion. “I think for my purposes it’s much easier to have these communications with each other [in person]. There’s a lot that we are missing when we have some folks missing on our little TV,” she said, referring to the large flat-screen television that displays video and plays audio of those who connect remotely.

Meeting in person is nice, for sure. But it’s hard to square Henden-Wilson’s claims with broad experience since March, 2020. After nearly four years of American society running fully or partly on remote meetings and presentations, there’s no evidence that form of communication has undermined the ability to convey information to elected officials or somehow prevented local government from getting things done. In fact, even with differences created by the technology, in both cases it’s almost certainly the opposite.

When pressed by Berkshire Eagle reporter Heather Bellow, who pointed out that hybrid meetings already allow both in-person and remote participation, Henden-Wilson and Ketchen raised their voices, Bellow reported. Ketchen then referenced a past that sounds idyllic for those who might prefer to keep a tight lid on topics for discussion and limit broad public participation: “Before COVID started,” Ketchen said, “you had to come here in person and be on the agenda.”

His opinion today is, perhaps, an evolution of sorts from nearly four decades ago, when he was first chosen by his Alford neighbors for the Select Board. A week before that May, 1987, election, Ketchen told The Eagle that he was running for office in part because he saw a need for “more communications between town boards and officers and between town government and its citizens.” Back then, of course, there was no Zoom—or even a public Internet. But today, remote-video platforms are the most readily available way to increase that communication at modest expense and with little effort.

The board’s decision may also impact the demographic profile of those who can participate—notably the town’s substantial population of elders. The median age of full-time Alford residents is nearly sixty-three years old, among the oldest in the Commonwealth. And more than a quarter of Alford residents are over seventy years old, according to 2021 U.S. Census estimates. Elders in those age brackets sometimes have physical challenges—like vision problems that preclude driving safely at night or mobility issues that make inclement weather dangerous—that make a remote-participation option worthwhile.

Also shut out? Alford’s large number of weekend-home owners and part-time residents—taxpayers, if not voters—who are an important part of the community.

To be fair, the provided remote access has, in practice, been less valuable for Alford residents than for those in nearby towns. That may be, in part, because remote attendance for Alford meetings requires emailing someone at the town offices before each meeting to get access credentials. That’s likely kept participation lower than it would have been otherwise. And Alford has never made recordings of its meetings widely available via its town website, as done in nearby Egremont, which posts all recordings of its town boards within a day or two, and West Stockbridge, which also posts recordings of its Select Board meetings.

Among small communities, Alford is certainly not alone: As Bellow reported in The Eagle this week, seven small Berkshires towns whose meetings are not recorded by a cable-television franchise have now abandoned remote participation: Alford, Hancock, Tyringham, Peru, Cheshire, Adams, and Savoy.

But to ensure an informed electorate, more—not fewer—opportunities for participation, scrutiny, and information flow are needed. That’s particularly true in Alford, which does not have a monthly independent newsletter to provide detailed coverage of town boards like those found in nearby small towns: New Marlborough (The Five-Village News), Monterey (The Monterey News), Sandisfield (The Sandisfield Times), and in Great Barrington, Eileen Mooney’s indispensible The NEWSLetter. Only occasionally do Alford matters rise to the level of coverage in The Eagle, the county-wide daily newspaper, or The Berkshire Edge, south county’s digital-news outlet.

If there’s some irony in a decision to roll back use of modern technology in Alford, it’s that the town built its own gigabit-speed fiber-optic Internet service—wired to nearly every home—that’s among the best in the nation. And voters recently approved money to upgrade that town-owned infrastructure to make lightning-fast 10-gigabyte Internet speeds possible in the future. (Alfordians may eventually be able to use that incredible speed to watch high-quality video of … Egremont’s Select Board.)

Alford residents can simultaneously be grateful for Ketchen’s and Henden-Wilson’s commitment to the town and willingness to serve—for half a lifetime, in Ketchen’s case—while also expecting them to foster participation rather than stymie it. The board’s vote and two members’ sharp tone may, in the end, spark greater interest in its activities: Such a passionate defense of rolling back a tool for public participation can only raise suspicion, regardless of whether it’s warranted.

At a challenging moment for American democracy, raising one’s voice in defense of less transparency is not a good look—whether in Washington, D.C. or tiny Alford, Massachusetts.

∎ ∎ ∎