As plans for a PCB landfill in Lee, Massachusetts reach a critical stage, a group of Berkshire County residents rallied in Boston—near the headquarters of General Electric, the company responsible for dumping PCBs into the Housatonic River.

∎ ∎ ∎

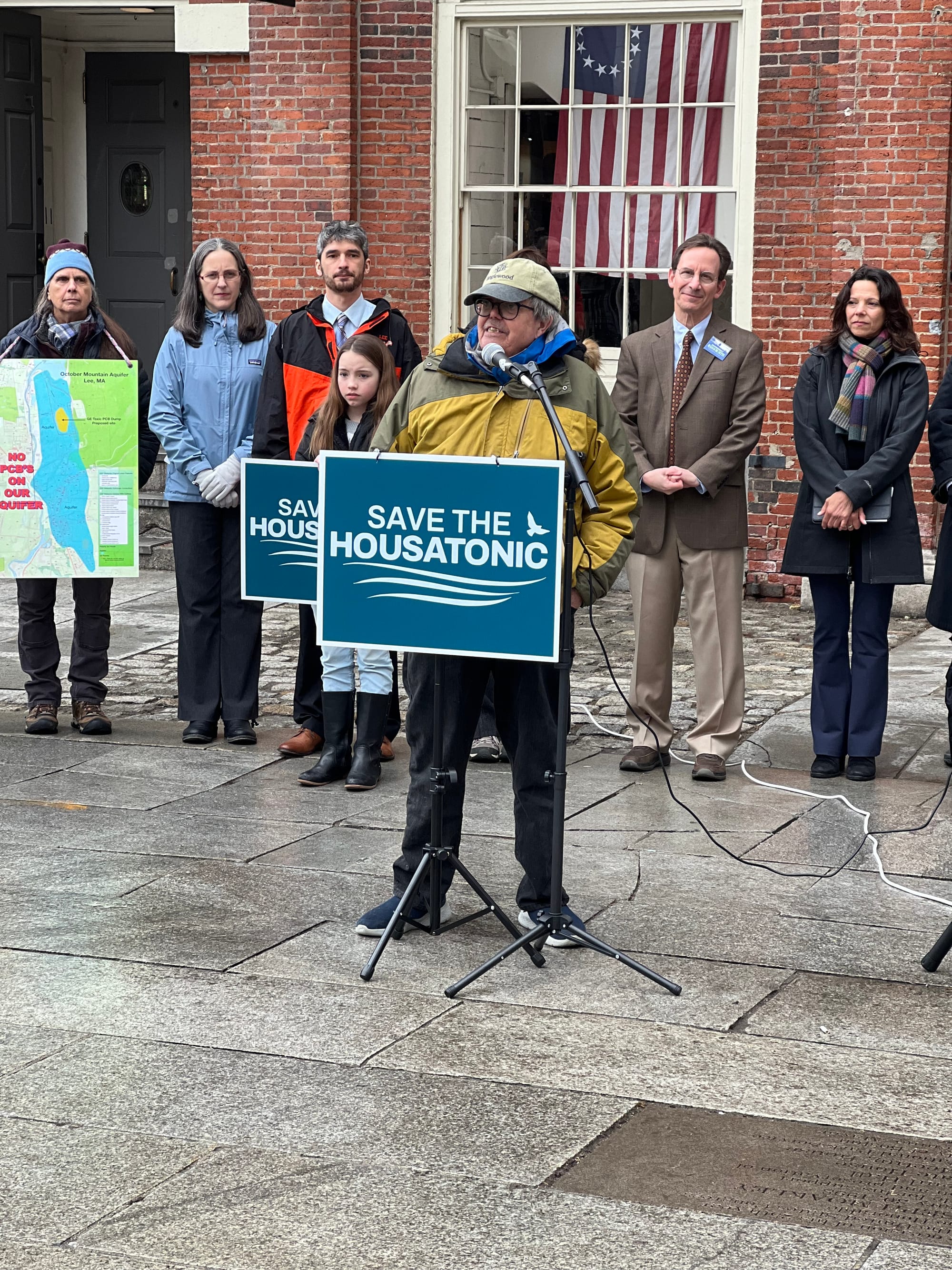

Just feet from an imposing bronze statue of the American revolutionary Samuel Adams—his face stern and arms crossed defiantly—residents and elected officials from the Town of Lee and other Berkshire County towns rallied outside Faneuil Hall in Boston yesterday, calling on General Electric to engage anew in discussions over the toxic polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, that pollute the Housatonic River.

They were small-town elected officials, longtime environmentalists, and a state representative. A fourth grader who loves to kayak. A retired primary-care physician who spoke of industrial chemicals that circulate inside infants even before birth. Some clean-water warriors urging an end to forever-chemical pollution now to avoid expensive clean-ups later.

And there was a community activist, now in his seventies, who’s been fighting since high school to hold corporate polluters accountable.

Intended or not, that they stood so close to a twenty-foot-tall Adams—a towering Revolutionary War-era figure—while delivering their remarks made sense: The Bostonian played a key role in rallying American colonists against what many believed was insurmountable British power.

In a 1771 Boston Gazette article, he warned against complacency and issued a call to action: “The necessity of the times, more than ever,” he wrote, “calls for our utmost circumspection, deliberation, fortitude, and perseverance.”

Adams published that piece and many others under the pseudonym “Candidus,” a Latin word that can represent truth, moral clarity, and a commitment to justice.

Yesterday, his call for “perseverance” echoed perhaps most of all. Many of those in attendance have worked on the PCB issue in the Berkshires for years, if not decades. They arrived on a bus chartered by a Berkshires-based environmental group so they could speak out near G.E.’s Boston headquarters, with the hope of drawing new attention to their cause.

With some holding up letters that spelled, “G.E. DO THE RIGHT THING,” around forty people listened as speakers derided the current Environmental Protection Agency-administered river-clean-up plan as insufficient, detailed the impact of PCBs on humans, wildlife, and the environment, and explained why they believe a confidential mediation process that produced the plan was flawed and undemocratic.

“We’re asking that there be no more toxic waste dumps in Berkshire County, none,” said Bob Jones, a member of Lee’s Select Board who has become a prominent voice in the years-long campaign. “We’re asking for a comprehensive, more effective cleanup of the river. How that can happen [is] by the town of Lee and the other towns sitting down, once again, with G.E. and the E.P.A. and interested parties, with scientists with various backgrounds, to look at this problem and come up with a long-term solution.”

Once widely used in industrial applications, G.E. relied on PCBs as a heat-resistant insulator in electrical transformers the company produced at a sprawling plant in Pittsfield. Along the way, it dumped hundreds of thousands of pounds of PCB-laden transformer oil down storm drains, across Pittsfield in buried barrels and contaminated fill, and into the Housatonic River. The chemical, considered a “probable” carcinogen by the E.P.A., was banned in the nineteen seventies.

Officials from E.P.A. Region One are charged with implementing the final phase of a consent agreement reached between the company and the federal government twenty-five years ago. They’ve long said that even if the plan for this “Rest of River” project only removes some of the PCBs, including from those areas with high concentrations, it’s far more protective of human health than leaving the chemicals where they are for years or decades longer.

🧵In #Boston, activists from #Lee and the southern #Berkshires challenged General Electric to "do the right thing" and advance a better cleanup of the Housatonic River: Remove more PCBs and use remediation instead of dredging/dumping a million cubic yards of PCB-tainted material in a new Lee dump.

— The Berkshire Argus (@berkshireargus.com) 2025-02-27T22:58:23.117Z

Most of those opposed to the new landfill still want PCBs removed from the river—but sent to existing out-of-state facilities. (That’s what E.P.A. originally proposed in a 2016 clean-up permit.) Or they want some or all of the PCB contamination addressed using current or future remediation technologies, some of which are being evaluated this year in an E.P.A. challenge-grant competition, and others that activists say have been used successfully outside the United States.

Under the current clean-up plan, only one hundred thousand cubic yards of the highest-concentration PCB waste will be sent out-of-state—a condition of the five-town deal with E.P.A. and G.E. that emerged, in 2020, from confidential mediation and that has survived legal challenges. G.E. opposed the 2016 permit because of the higher cost to ship all PCB-laden materials to distant waste facilities. Now, an estimated one million cubic yards of PCB waste is expected to be piled into the new facility in Lee over the next dozen-or-so years.

A Boston rally held as the clock ticks down

Yesterday’s rally was organized by the town’s year-old PCB Advisory Committee, and it came at a key moment: As the administration of President Donald Trump creates a path of destruction through federal agencies, including a promise this week to cut the E.P.A.’s budget and staff by sixty-five percent or more, the ability of the agency to effectively monitor the upcoming remediation work, as promised, is uncertain. (General Electric is legally required to pay for the project, estimated at more than six hundred million dollars, but with E.P.A. oversight.)

And with construction slated to begin sometime this year on the thirteen-acre engineered landfill, or so-called “upland disposal facility,” at an expansive former sand-and-gravel pit in Lee, the window is closing for those who still hope to stop it.

Tim Gray, a longtime environmental and community organizer whose Housatonic River Initiative paid for the bus to Boston, walked gingerly to the microphone yesterday, having suffered a recent fall on some late-winter ice. He recalled how, as a student in 1976, he and a few others received a grant to test the Housatonic River for PCBs. The water south of Pittsfield, he said, was “chock full” of the toxic chemical.

“We wrote [to] G.E., we wrote the E.P.A., we wrote the Massachusetts [Department of Environmental Protection], telling them that this was very contaminated, and we were very concerned about it,” he said. “And they wrote us back and they said, ‘Oh, you guys don’t know what you’re talking about because you’re a bunch of undergraduates.’”

Gray said friends and neighbors who lived near the river have died from cancer over the years, including five in the last year. He blames PCBs.

Fresh off her swearing-in last month, State Rep. Leigh Davis, a Great Barrington Democrat who represents the eighteen communities of the Third Berkshire district, called for “collaboration” and for the voices of residents to be “respected.” And she hinted—more clearly than she did during her 2024 campaign—at stronger opposition to a new PCB landfill in Lee.

“The proposed upland disposal facility is not a solution if it creates new risks for our communities,” Davis said. “We need a clean-up that truly cleans, not one that relocates contamination from one part of our community to another.” That echoed what Jones and Sean Regnier, another member of the Lee Select Board, also said yesterday.

By now, of course, the talking points are familiar. And the path to a radically different clean-up plan is, perhaps, narrow at best.

But things could change: A pending lawsuit brought by the Town of Lee against G.E. and Monsanto—the company, now owned by Bayer, that manufactured PCBs from the nineteen thirties to the late nineteen seventies—for environmental harms is awaiting a federal judge’s ruling on the companies’ move to dismiss the case. If it goes forward, the lawsuit could give the town leverage to open a new conversation with G.E.—and also potentially deliver funds that could be spent toward a clean-up more to their liking.

While their case is complicated by the existing consent decree that already makes General Electric financially liable, at least for some river clean-up, town leaders remain optimistic. They know that over the last two decades, Monsanto has paid nearly three billion dollars in settlements and jury verdicts from PCB litigation brought by states, counties, municipalities, and individuals.

That includes a one-hundred-million-dollar verdict delivered just last month as part of an ongoing Washington state lawsuit over the health impacts of PCBs, including cancer, thyroid disorders, and neurological injuries. In that case, a jury concluded that Monsanto had knowingly concealed information about the dangers of PCBs—an argument that is also central to the Town of Lee’s lawsuit.

Hopes for a fishable, swimmable river for future generations

The youngest of yesterday’s speakers was Jenny Hogencamp, a fourth-grade student at Lee Elementary School whose family lives about a mile from the Housatonic River and the heavily polluted Woods Pond.

“If the river was a clean, safe environment, me and my family would have a place to fish, kayak and swim close by,” she said, noting that today, her family drives somewhere else when they want to put their new kayaks in the water.

Hogencamp, like the others, has a vision for the future. “Someday, I hope to be able to ride my horse down to the river and [Woods] pond and not worry about exposure to the chemicals in the water,” she said. “I hope G.E. ends up doing the right thing and doesn’t make a decision that will continue to hurt our environment and town.”

∎ ∎ ∎

Want to see more stories like this? Please support independent nonprofit journalism by subscribing for free or becoming a contributing member. (All contributions are fully tax-deductible.)

Have thoughts? Submit a letter to the editor.