The birthplace of the Renaissance confronts a housing and identity crisis fueled by short-term rentals.

∎ ∎ ∎

It only takes a day or two of walking the stone-paved streets and lively piazzas of Florence to feel the city’s long history, notice the style and relaxed manner of its residents, and appreciate a commitment to low-stress living—at least compared to productivity-obsessed cities and cultures elsewhere.

Take in the scene from atop a bridge that spans the city-dividing Arno River, like the centuries-old Ponte Vecchio, and you’d be forgiven for thinking you’re on an elaborate movie set where a director is busy shooting a film about … life in Florence. The city and its characters have cinematic flair.

There’s a certain intentionality to that Florentine mix of vibrancy and easygoingness. As residents and tourists squeeze past each other on too-narrow sidewalks and glide between motorbikes and scooters traveling chaotically in all directions, the Italians stubbornly refuse to notice. Or, it seems, to mind at all. It’s rare to hear car horns or yelling motorists.

But drop the city of Florence, as is, into the United States and it’s easy to imagine a ceaseless din of honking, streams of expletives, and exasperated cries of, “Just GO already!”

Some truth: All that’s appealing about the Berkshires will never match what’s offered by the art, history, and culture of Florence. Despite our beautiful vistas, cultural amenities, and outdoor-recreation opportunities, when compared to Florence our attractions have, well, a less substantial feel. Sparking the Renaissance more than half a millennium ago can do a lot for a place, it seems. So, hat tip to Dante, Brunelleschi, Donatello, and that whole crew.

Even our most impressive local icons and attractions, like the singer James Taylor—whether at Tanglewood, on the road from Stockbridge to Boston, or sharing how sweet it is to be loved by you—face stiff competition from the historical gravity and cultural heft one feels inside the thick stone walls of a thousand-year-old neighborhood church. Or, while absorbing the trajectory of Medieval and Renaissance art at the Uffizi Gallery (established 1581), or spending a breath-catching hour gazing at all seventeen feet of Michaelangelo Buonarroti’s David, completed in 1504, as the miraculous statue ponders his next move against a giant while holding court at the Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze.

In some ways, conceding that Florence’s attractions outshine our own may be a good thing: During my family’s recent stay in the city’s Oltrarno district—still a few months out from the busy summer season—a roiling sea of tourists flooded the neighborhood’s narrow streets at all hours. They were on their way to and from historic sites like the Medici family’s longtime home, the Palazzo Pitti, with its adjacent hilltop Boboli Gardens, as well as assorted restaurants, cafes, and, by my unofficial count, more than four million gelato shops offering at least six thousand different flavors.

After nine in the morning, the neighborhoods close to the Arno and in the city center took on the vibe of a too-crowded state fair, or oversold music festival, or the first moments after a cruise ship’s passengers disembark for their mad, two-hour visit to an island’s duty-free marketplace. Still, we managed to find restaurants favored by locals and, at times, immerse ourselves in the everyday life that unfolds far from tourist masses. (Tourists ourselves, admittedly.)

Crowds have long been part of any quest to breathe in Florence’s endless supply of Renaissance majesty, but queues of hundreds and sometimes thousands are now common. These days, walking the halls of the Uffizi to see Leonardo da Vinci’s Adoration of the Magi and Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus means giving up, for hours, any notion of personal space. Claustrophobia is included in the ticket price.

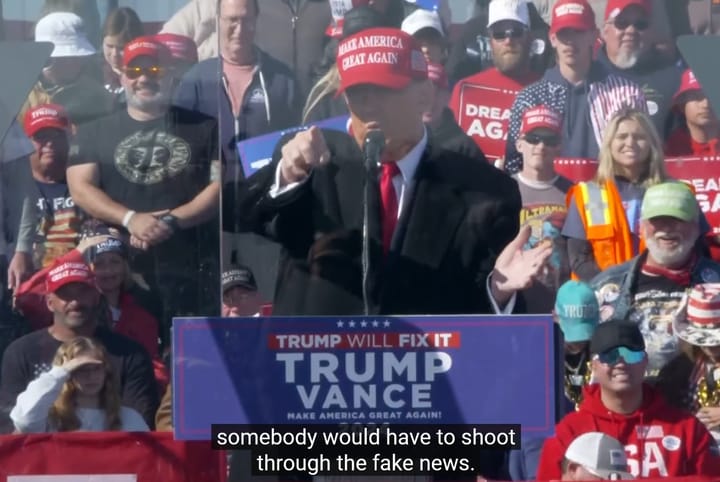

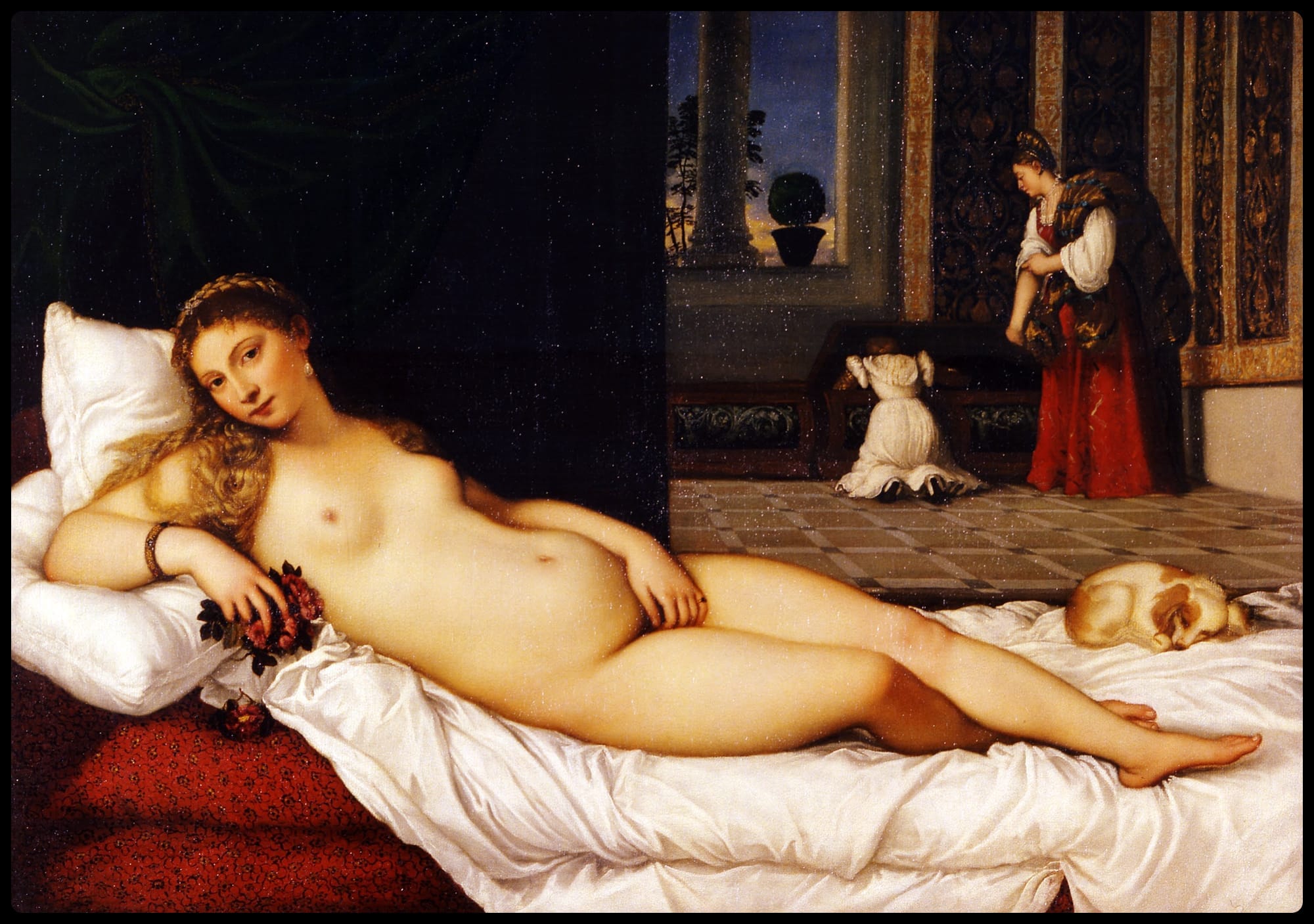

Some observers have had a different opinion of whether some of these sights—and, by extension, today’s long lines and non-socially-distanced crowds—are worth it. Near the end of his 1880 travelogue, “A Tramp Abroad,” Mark Twain called Titian’s naked “Venus of Urbino,” also on display at the Uffizi, “…the foulest, the vilest, the obscenest picture the world possesses.” (Signore Clemens, please, step this way and let me introduce you to the Internet.)

Though, to be fair, his two-page rant about the painting wasn’t really commentary on her lack of wardrobe. It was about courtesies extended to “Art” in museums that he said weren’t permitted on the page. “I should like to describe her—just to see what a holy indignation I could stir up in the world—just to hear the unreflecting average man deliver himself about my grossness and coarseness, and all that,” he wrote.

Twain’s tangential complaint aside, the city’s near-miraculous artifacts and endless historic and cultural sights drive a tourist-based economy that employs many thousands of Florentines. But acknowledged overtourism, driven in large measure by a long-unrestricted short-term-rental market, has left the city mired in a housing and identity crisis.

It was little surprise, then, that a study last year by two Italian academics found that almost thirty percent of homes in central Florence were listed on Airbnb. An earlier study looked at the concentration of short-term rentals and found that nearly two-thirds were in an area of just five square kilometers in the city center, an area that’s been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site for the last four decades. And another study completed last June by three academics at the University of Florence noted that Florence has the highest number of Airbnb listings (15.3) per thousand residents in the world.

And so last October, frustrated by a lack of requested federal action, Florence froze new short-term-rental licenses in its city center, pointing to an increase from 6,000 listings in 2016 to what officials say is more than 14,000 today. For those living and working in the city, average rent is up forty-two percent over those eight years. Some of the city’s historic stone apartment blocks have been decimated, with few neighbors for the left-behind, full-time residents to get to know.

Dario Nardella, Florence’s mayor since 2014, championed the limit as an important starting point. He’s called for more significant national regulation. “The 40,000 Florentines who live in the [city] center are complaining about finding themselves, all of a sudden, living in apartment hotels,” he said at a press conference in October, noting that rents had climbed another fifteen percent over the previous year. “The consequences are there for all to see: loss of identity of the historic center, housing insecurity, rising cost of living and a drastic reduction in available housing,” he later wrote on social media.

Not surprisingly, various real-estate and pro-business guilds shrieked at the prospect of limits, vowing lawsuits and threatening disaster for the tourism-based economy. As if Florence didn’t thrive as a tourist hub long before the arrival of the Airbnb app in 2008.

But full-time residents, students, and others have increasingly fled to the outskirts of town, and beyond, chased away by rising rents and vacation rentals that have hollowed out entire buildings and blocks. High rents across Italy led to student protests last year that included camping out overnight in front of their universities. A remarkable seventy percent of Italian college students live at home with their parents, as compared to seventeen percent across all European Union countries.

In the city center, apartment-building doorways reveal the modern story of Florence: Rows of combination-controlled lockboxes that hold apartment-door keys for vacationers. As a result, the city has lost some of the shops and stores that locals can afford to establish, run, and patronize—the kind that make Florence, Florence. (Or anyplace, anyplace.) They’re being replaced by others that cater to tourists and to those—residents and visitors alike—who can afford to spend more, something that will sound familiar to anyone observing that years-long trend in Great Barrington.

In some cases, Florence’s quaint cafes and local wine bars have been replaced by more of those gaudy souvenir shops that hawk “I ❤️ Florence” T-Shirts, refrigerator magnets of David’s privates, and knit winter hats made to look like the dome of Brunelleschi’s majestic, fifteenth century Duomo cathedral.

(Yes, there are such refrigerator magnets. No, there weren’t really any Duomo winter hats. But perhaps a more determined search might uncover one—or something very similar—in at least one tacky souvenir shop?)

The new short-term rental freeze, and an offer of three tax-free years for property owners who switch a vacation rental to a long-term rental, are both meant to help address problematic overtourism—swarms that fill the city’s narrow, winding streets, often with to-go sandwiches in hand and mouth, making the avenues look like a “feeding trough,” according to media descriptions dating back to before the pandemic. It’s a stark reminder that too much tourism can undermine the reasons people want to visit a place, much less keep it attractive to those who live there year-round.

In Florence, it’s unclear that freezing the status quo will do nearly enough; under discussion are proposals to end full-home rentals, similar to recently implemented limits in New York City, and limiting each host to a single listing—something comparable to Great Barrington’s new limits. Other Berkshires communities may need to consider all of these ideas, and perhaps others, as they craft, at long last, their own regulations and limits on housing turned over to vacation rentals. Whether they’ve waited too long to act remains to be seen.

Full disclosure: Our extended family of seven, including my partner’s mother on her first-ever trip abroad, stayed in an apartment rented via the home-sharing app VRBO. The cost of traditional hotel rooms for all would have been cost prohibitive—precisely the argument made by those who oppose any and all restrictions. Aside from saving money, staying together in one large apartment was among the joys of the trip. And that’s something travelers have come to expect and enjoy in the Airbnb age. (The moral cost of contributing to the crisis in Florence has not passed us by without discussion; indeed, it’s weighed more heavily as I’ve researched and written these words.)

All of this speaks to the challenge for both Florence and our own region, where a years-long housing crisis shows little sign of easing: How to strike an appropriate balance among tourism-economy essentials like hotels and homestay rentals, housing and amenities for residents and workers, and the darkly ironic need to allow full-time residents to list their homes for short-term rental, at least some of the time, so they can afford to remain in communities made too expensive … by short-term rentals.

In Florence, where the genius of Michelangelo and da Vinci helped place creativity and inventiveness at the heart of the modern world, the city of 360,000 residents has not yet solved its housing and overtourism crises. Parallels with the southern Berkshires are plain to see, as is the only path forward: Bold, urgent, more innovative, and likely expensive action to add additional housing and preserve existing homes for those who live and work here.

∎ ∎ ∎