According to Fairview Hospital officials, each year around fifteen air-ambulance flights lift off from Great Barrington Airport. Here’s how those flights work—and how they fit into our rural health-care system.

∎ ∎ ∎

Early on a May afternoon in 1955, a piston-engine Bellanca Crusair accelerated down the unpaved runway at Great Barrington Airport. Lifting off and rising slowly above the Egremont Plain, the pilot, Walter J. Koladza, banked the airplane away from the small airfield that would, early in the next century, be named for him. His destination? Boston, about 120 miles and less than an hour’s flight-time away. And his project? Pick up a case of the recently approved Salk polio vaccine and rush it back to the Berkshires so that inoculations could begin as soon as possible.

Koladza stepped in after a plan to mail the vaccine doses went awry. Thanks to his quick out-and-back flight (he was home in Great Barrington before 5 p.m.), within days a few hundred of the youngest children in Great Barrington, Egremont, Alford, and other nearby towns had received their first dose.

Transport by air made sense because there was urgency, particularly as summer approached. Outbreaks of polio, which caused devastating childhood paralysis and disability, had increased in frequency and size during the previous decade, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the late 1940s and early 1950s, precautions like those implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic were, at times, common: Stay home, avoid large public events, carefully choose with whom to spend time, isolate the sick, and impose quarantines for those possibly exposed. When the Salk vaccine was approved in April 1955, there was no time to lose.

In those days, the airport on Egremont Plain Road—owned by Koladza from 1945 until his death in 2004—was sometimes used for medical emergencies. In 1949, a recently retired Alcoa executive named George J. Stanley was visiting from Pittsburgh and staying at downtown Great Barrington’s popular Berkshire Inn. But then he “took ill,” according to a Berkshire Eagle story. An ambulance rushed him from Fairview Hospital to the airport to meet a waiting National Guard C-47—a twin-engine military transport based on the civilian Douglas DC-3—that then flew him to Boston for treatment.

That kind of emergency medical-transfer flight wasn’t available to everyone like it is today: Stanley’s son was a colonel in the Connecticut Air National Guard based in Hartford and likely pulled a few strings. The elder Stanley recovered and lived until 1960; his son rose to brigadier general in the Connecticut National Guard and retired to Florida.

That intersection of aviation, the military, and urgent medical services dates from the earliest days of flight during the first World War. The logic was, and remains, quite simple: The faster a patient reaches medical resources to treat their illness or injury, the increased likelihood of survival and recovery. Testimony presented to the Great Barrington Selectboard during a recent airport-related hearing included stories of just those kinds of time-sensitive, lifesaving interventions that include a helicopter flight.

The growth of EMS and helicopter air-ambulance flights

In the late 1960s, helicopters like the Bell UH-1 “Huey” used by the U.S. Army to transport wounded soldiers in Vietnam began appearing stateside for civilian medical transfers. Using helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft for medical transport certainly wasn’t new: Particularly in remote locations in the United States and around the world, it was not uncommon to fly patients to where they could receive needed medical care. But it wasn’t organized.

The first civilian, hospital-based helicopter program was established in Denver, Colo. in 1972 and called Flight for Life Colorado. A year later, with passage of the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Systems Act by Congress, $185 million in federal funds started flowing from Washington to help plan and establish regional EMS programs. That led to a steady increase in the number of emergency-medical technicians (EMT) and more highly trained paramedics affiliated with municipal fire and ambulance services.

Some argue that the television series “Emergency!,” which premiered in 1972 and aired for six seasons, also helped increase support and funding for EMS. Handsome and daring, firefighter-paramedics John Gage and Roy DeSoto—and their life-saving rescues and high-speed delivery of patients to the fictional Rampart General Hospital—certainly gave the vital work of first responders some 1970s Hollywood gloss.

Overall, expanding EMS resources helped address what a 1972 U.S. Senate report suggested could be 67,000 lives saved every year with widespread deployment of EMS programs. By some accounts, by the early 1980s, roughly half of Americans could be reached within 10 minutes by some kind of emergency medical service.

A slow-but-steady rollout of 911 networks also played a role. First proposed in 1957 by the National Association of Fire Chiefs as a single number to call to report fires, by the late 1960s, it was inaugurated as a single number to dial for all emergencies. It took decades, but today more than 98 percent of communities in the United States utilize 911.

A variety of medical-air-transport programs soon followed. At first, they were exclusively hospital-affiliated or nonprofit helicopter air ambulances (HAA), also known as helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS). In Massachusetts, the first hospital-based air ambulance was established at Worcester’s UMass Memorial Hospital in 1982. Called New England Life Flight (a host of HAA and HEMS services use some version of that apt descriptor), it continues to operate. Today there are more than 1,100 air-ambulance bases in the United States and roughly 300 different providers. And according to data from the Center for Insurance Policy and Research, there are more than 550,000 air-ambulance flights per year.

Since 1982, the industry has evolved dramatically, largely because of a 2002 change that allowed private companies into the industry alongside hospitals and nonprofits. In recent years, many independent providers of these flights have been rolled up by, or are affiliated with, two private-equity-backed companies: Air Methods, a provider of air-ambulance services owned by investment firm American Securities, and Global Medical Response (GMR), a roll-up of other companies that’s owned by the firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR). These two companies currently control approximately two-thirds of the air-ambulance industry, according to Medicare data. GMR, through its subsidiary American Medical Response, is also the largest provider of ground-ambulance service in the United States.

As a result, over the last two decades, the cost of helicopter air-ambulance flights has skyrocketed. Numerous government reports and academic studies have documented the rapid increase: Between 2008 and 2017, the median price for a helicopter air ambulance flight increased from $12,500 to $35,900. And because helicopter services are called in an emergency, and many providers are out-of-network for patients with private insurance, until last year, those enormous charges could be passed on to patients in “surprise bills.” (A 2019 General Accounting Office study found that 69 percent of helicopter transports of privately insured patients were out of network.)

How helicopter air-ambulance calls work

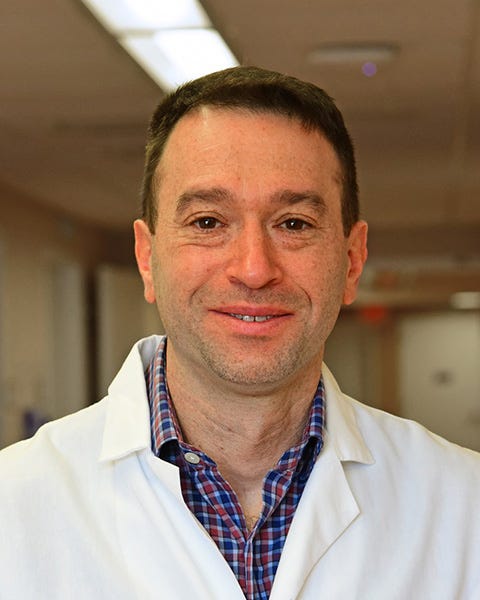

Last fall, I spoke to Alec Belman, the longtime Fairview Hospital emergency-medicine physician who recently became the 110-year-old hospital’s medical chief of staff, to learn the details of medical helicopter use in Berkshire County. In an interview, he told me that, based on a review of hospital records, over the last decade there have been around 15 helicopter-air-ambulance transfers from Fairview per year, or what he said were roughly one or two per month. He said that average has probably been the same since he started at Fairview in 2007 and has remained steady throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

(DISCLOSURE: I have received medical care four times since 2008 from Fairview’s emergency-medicine department.)

That number represents flights that transfer patients from Fairview to other hospitals via helicopters that land at the Great Barrington Airport. It doesn’t include the handful of “on-scene” helicopter landings at the site of serious automobile accidents and other incidents where patients with traumatic injuries bypass the hospital and are flown immediately from the scene to a hospital trauma center, usually in Springfield, Hartford, Boston, or Albany.

Belman told me that most transfers from Fairview are related to heart attacks, strokes, and other issues where rapid intervention—including emergency surgery—is needed. “It can be people with severe medical illnesses like internal bleeding that’s not due to injury,” he said, describing time-sensitive health issues. But ground transport to reach Albany, Hartford, or western Massachusetts’ only Level I trauma center at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield can take hours. “People who need intensive-care-unit-level care, the less time they’re in the back of an ambulance the better,” Belman said. “[Helicopters] shorten the time necessary to get to a very distant hospital that has resources that are only available there.”

Another advantage is the expertise of the helicopter’s critical-care medical team. “Helicopter transport is usually quicker but always brings a bigger skill set to the patient’s bedside, which is one of the other key reasons to do it,” he said. The condition of the patient, the type of equipment being used in their care, as well as medications being administered may call for a level of care beyond what an ambulance crew’s EMTs and paramedics are trained or licensed to provide.

That means it’s not only speed of transport that’s a factor, Belman told me. “The people in the back of the helicopter—a nurse/paramedic and a respiratory therapist who have a broader skill set and usually a longer period of training—are licensed to manage a more acutely ill patient enroute,” he said. Belman also said regulations require that certain seriously ill or injured patients be transferred to other facilities only via critical-care-rated transport, which in this region is only available via helicopter.

Helicopters supplement limited ambulance resources

Helicopters are sometimes called not simply because speed is required but also in recognition of the ongoing struggle in south Berkshire County with ambulance resources, Belman said. Sending a patient via ground to a distant hospital takes an ambulance and its crew out of service for other local needs for hours.

“In a small-town hospital, [helicopters are] another resource that we can call on,” he said. “Because our local ambulance service has two ambulances on [call], at most, at one time. And if we pull one of them to go three hours away, that leaves [only] one ambulance. So that’s a consideration for us.”

He described a situation earlier that day when Fairview’s medical staff decided to send two patients to hospitals in Westchester and Hartford for next-level treatment. “Both were for really serious things. We chose to fly the person going to Westchester so we could use one ambulance to take the other patient to Hartford and maintain one ambulance for our service area,” he said. “So strategically, [helicopter transport] is another option for us.”

According to Kevin Wall, the recently named chief of operations of the Southern Berkshire Volunteer Ambulance Squad (SBVAS), the organization tries to have two ambulance crews available at all times. He told me this week that in 2022, its three identically outfitted ambulances responded to a total of 3,081 calls. That includes 1,947 in response to 911 calls, 1,061 inter-facility transfers, and 66 “intercepts” where a SBVAS ambulance and paramedic meet another town’s ambulance and EMTs to provide additional emergency medical care to a patient. SBVAS doesn’t call for helicopters, Wall said, but transfers patients to the nearest facility, like Fairview, where an inter-hospital-transfer decision can be made. (SBVAS may also be at the site of serious accidents along with the fire department when a helicopter is called directly to the scene.)

SBVAS, which has been a nonprofit since 1968 and today has both paid and volunteer staff, provides services to eight South County communities, as well as that intercept service for at least four more. But along with other EMS providers nationwide, it’s facing financial and operational challenges. Its representatives recently made the rounds to local select boards seeking annual direct funding.

SBVAS Board President James Santos told the Great Barrington Selectboard earlier this month that the organization faces several challenges: a region with an increasingly elderly population and Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates that he said don’t cover actual costs; difficulties with recruitment and retention of EMTs and paramedics; and a shift from volunteer to paid staff. “For years, we have provided town ambulance service for free,” Santos told the Selectboard. “We can no longer operate that way. We need financial support from [service-area] towns to continue,” he said. SBVAS requested more than $150,000 from the town of Great Barrington for the next fiscal year, and smaller amounts from the other communities it serves.

With those limited ambulance resources in mind, Belman told me there is constant communication between local EMS services and hospital staff so there’s awareness of available ambulances and crews. “We have an EMS radio so we hear what’s being called out over 911 and [can] make some bigger decisions,” he said. “Part of the job certainly is looking at South County resources and utilizing what we can from outside of the area,” he said, referring to the helicopter air-ambulance option. “Sometimes it’s really about managing the big picture,” Belman said.

The decision

What else goes into the decision to request a helicopter air ambulance? Belman said the emergency-medicine team identifies the most appropriate hospital for the patient, confirms it has available capacity, and then consults with the receiving facility’s doctors who will take on the patient’s care. If they determine helicopter transport is best for reasons of speed, medical support enroute, or because of considerations related to local ambulance resources, the hospital calls the three primary air-ambulance providers located in Albany, Hartford, and near Springfield to find an available helicopter and crew.

Once a helicopter is enroute to Great Barrington, a local ambulance is dispatched to meet them at the airport. The ambulance then brings the helicopter’s medical crew to Fairview, located just under three miles away. They consult with Fairview’s medical staff, evaluate the patient, and prepare them for travel, which Belman said can take “anywhere from five minutes to a half-hour.” Patients are loaded onto a special transport stretcher and returned via ambulance to the airport. Simple “load and go” operations can have the helicopter’s medical crew and patient back at the airport in 20 minutes, while other transfers take longer, he said.

But weather is a significant factor. Belman estimated that perhaps a third of the time—and sometimes more—weather doesn’t cooperate and helicopter transfer is not possible. He recalled instances when a helicopter was already enroute, or even close to landing in Great Barrington, when it turned back because of high winds or other unfavorable conditions.

There are strict protocols for when air ambulances can fly. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) began to look closely at air-ambulance safety following accidents in 2004 and 2005. And in the wake of 21 deaths in medical-helicopter crashes in 2008, including six crashes in just two months, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and NTSB focused on updating regulations to improve HEMS safety.

In 2015, the FAA issued a directive mandating enhanced air-ambulance pilot training and certification, better pre-flight risk-analysis procedures, additional on-board flight-safety equipment, and more stringent rules about weather conditions. Today’s rotor aircraft used in HEMS may include technology that provides pilots with vital information when flying at night and in unfamiliar terrain. That includes instrumentation that doesn’t interfere with night vision imaging systems, and terrain-awareness systems that model possible dangers.

“On-scene” helicopter landings

Inter-facility transfers from Fairview are different from emergency on-scene helicopter pick-ups at accident sites. Belman said the latter don’t usually involve Fairview, though emergency-room staff are available to consult as needed. “There’s a very-well-written state protocol for paramedics as to what meets what we call ‘trauma system entry criteria,’” he said. Paramedics at the site of an incident like an automobile accident or wilderness extraction evaluate injuries and quickly determine if transport directly to a Level I trauma center—the best equipped—in Springfield, Albany, or Hartford is needed. “And if the weather’s good,” Belman said, “they’ll call for a helicopter at the scene because that gives the patient the best chance of making it.”

Those calls require the Fire Department to establish an on-scene landing zone, which Great Barrington Fire Chief Charles Burger told me requires a truck and four firefighters. He said there are usually a few on-scene calls each year, but their frequency is, by their nature, unpredictable: Last August there were three calls for helicopter air ambulances at the scene of serious incidents in Great Barrington in just one week, Burger said.

In those situations, the Fire Department establishes a landing zone as close to the accident as possible, following well-established protocols, and communicates with the incoming air crew to ensure safety. According to landing-zone instructions Burger sent me, which reflect guidelines used across the country, a 100-by-100-foot landing area on flat ground is delineated with strobe lights at each corner, and the nearby area is examined for loose debris that might be kicked up by rotor wash. Ideal landing zones are also free of obstructions like nearby trees and utility wires.

From there, patients are loaded into the helicopter and flown directly to a hospital trauma center. The landing zone is maintained for a few minutes after departure in case the helicopter needs to return. Belman told me that he recalled a handful of cases over the years where accident victims were taken by ambulance to meet a medical helicopter at the airport, presumably because of challenging conditions for landing at an accident scene.

How it works at BMC in Pittsfield

Many assume that the Berkshire Medical Center (BMC) campus in Pittsfield—the largest hospital in the county and a Level III trauma center—includes a helipad. But that’s not the case. Since the early 1980s, helicopter air ambulances have landed in the parking lot of nearby Wahconah Park, located about 1,000 feet from the hospital. Before BMC secured that permission in 1982, patient transfers to helicopters were made at Pittsfield Municipal Airport, which is a little more than five miles away.

According to Berkshire Health Systems (BHS) spokesperson Michael Leary, for the 12 months ending September 30, 2022, there were 144 helicopter air-ambulance flights that transferred patients from BMC to other facilities.

When I spoke recently to Matthew Risley, a lieutenant in the Pittsfield Fire Department (PFD) who is also president of Pittsfield Firefighters Local 2467, he walked me through the steps to establish a landing zone at Wahconah for each of those flights.

When a helicopter is dispatched, a call is made to the PFD and it sends a truck and three firefighters to the Wahconah parking lot, he said. As with landing zones set up by the Great Barrington Fire Department, the protocol is well-established: Mark the landing zone, keep people and cars out of the area, communicate with BMC security and the helicopter’s pilot, and coordinate with the ambulance that will transport the medical team and the patient. After the helicopter lands, firefighters remain at Wahconah until the medical crew returns with the patient and departs, Risley told me.

If an event at Wahconah—home of the Pittsfield Suns baseball team—precludes its use for a helicopter landing, a field at John T. Reid Elementary School about a half-mile from the hospital was used in the past. But Risley said Pittsfield Airport is now the preferred alternate location. “So in the summertime when there’s a baseball game they might have to go to the airport,” he said.

Risley couldn’t recall any instance when the PFD truck and firefighters at the landing zone were pulled away to respond to another emergency. In that situation, he said, BMC security would still be at Wahconah to await the return of the medical crew and patient.

He also told me he’s noticed an uptick in helicopter transfers from BMC recently that he thinks could be related to limited ambulance resources—like the challenge in south Berkshire County—and also because of other health-care needs like pediatrics and neonatal care. “It seems like it’s expanding … I’m not sure what the reasons are for the spike, but this year the numbers have gone way up,” he said.

A helipad at Fairview?

In Great Barrington, landing those 15 or so flights a year directly at the hospital would save precious time by eliminating the back-and-forth to the airport, and, importantly, keep ambulance crews free for other urgent calls. So why doesn’t Fairview establish a helipad right at the hospital? “That’s been a point of conversation,” Belman told me.

He said Fairview has considered locating a helipad in the large parking lot south of the main entrance. In its annual Community Benefit Report filed with the state attorney general in 2017, Fairview officials reported that in 2016 they undertook “a formal review of the feasibility of locating a helipad on the hospital campus.” That included examination of the “costs, benefits, and restraints of a proposed site at Fairview Hospital.”

That evaluation was listed in the report among the hospital’s “Rural Community Emergency Response Capacity Building” goals, which highlighted Fairview’s vital role as the region’s critical-access hospital. To that end, it partners with a host of local organizations and service providers to deliver care to the surrounding rural communities. In that state filing, a helipad was described as something that would “enable emergency responders to raise the level of care in the field” and help “assist rural emergency teams to function at a high standard of care.”

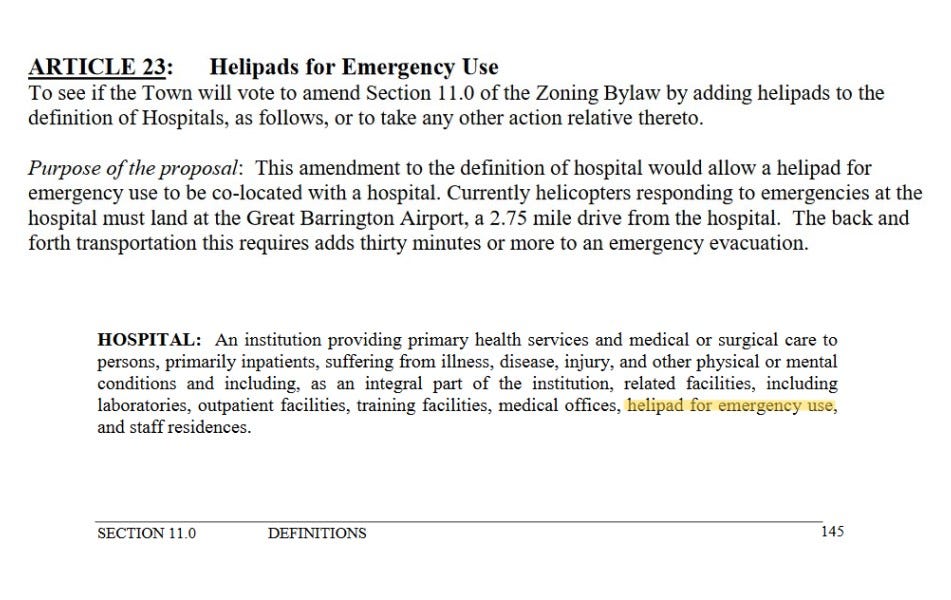

The hospital’s consideration must have been serious: In January 2016, it dispatched local attorney Kathleen McCormick to a Great Barrington Planning Board meeting to propose a change to the town’s zoning bylaw to permit a helipad in the hospital’s Berkshire Heights residential neighborhood. According to minutes of the meeting, the board determined the best solution was to expand the bylaw’s definition of hospital facilities to include “helipad for emergency use.” A public hearing on zoning-bylaw changes a couple of months later included little comment on the helipad proposal and it was forwarded to town meeting for a vote.

The May 2016 annual-town-meeting warrant described how medical transfers from Fairview are delayed by use of the airport for air-ambulance flights. “The back-and-forth transportation [between the airport and hospital] adds thirty minutes or more to an emergency evacuation,” explained the Planning Board’s justification for the zoning change. The Selectboard also recommended approval and the helipad proposal was adopted with no discussion.

Belman said that Fairview’s investigation identified a few challenges. Most significant was the loss of what he said could be 100 parking spaces. A helipad would also require relocating some overhead wires and addressing concerns neighbors might have about noise. “Our property is not the ideal place for helicopters to land,” he said.

Speaking of both BMC and Fairview, he said on-site helipads are the best option. “Ideally, we’d all have helicopter landing spots on top of our roofs or in our parking lots. [But] sometimes that doesn’t work out,” he said. The primary obstacle for Fairview wasn’t cost, he said, but physical space. “We just don’t have another spot where we can park 100 cars.”

Fairview’s 1979 helipad construction

If there’s an intriguing historical footnote to Fairview’s recent consideration of a helicopter-landing site, it’s that the parking area Belman said would be lost was originally built to serve as a helipad.

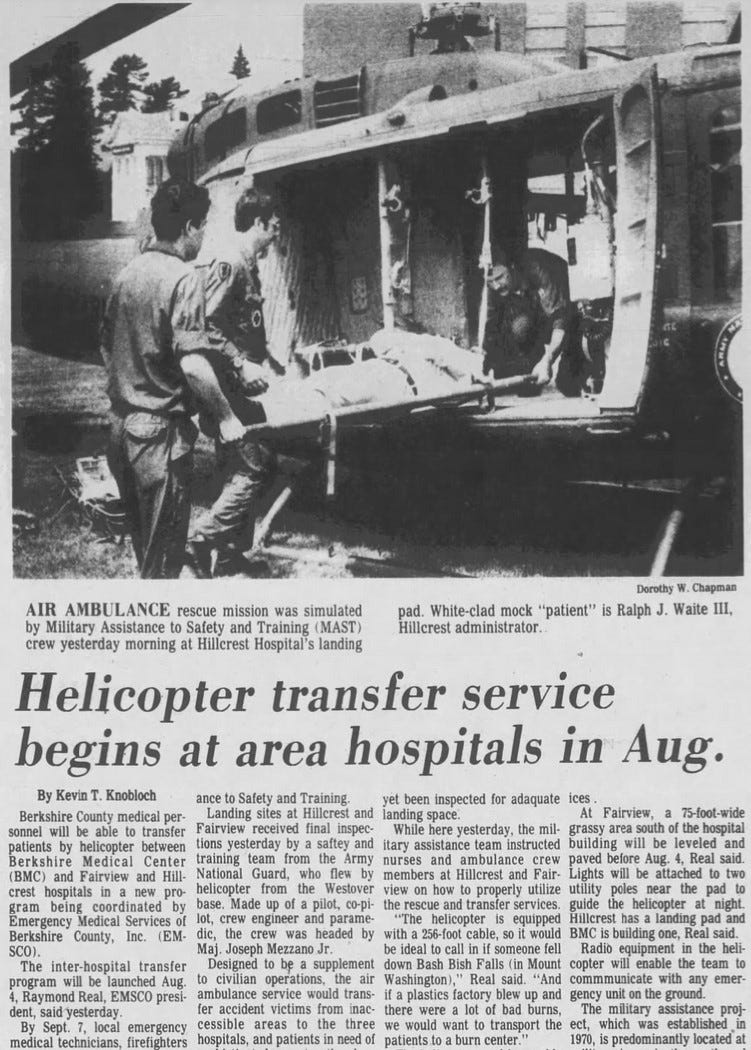

In the summer of 1979, Fairview signed on to a helicopter-transfer service coordinated by Emergency Medical Services of Berkshire County. It utilized helicopters dispatched from the enormous Westover Air Reserve Base in Chicopee that would land at Fairview and transport patients to other hospitals. The program was part of a military-civilian partnership called Military Assistance Safety and Traffic (MAST) that was eyeing a similar arrangement at Pittsfield’s Hillcrest Hospital. (Hillcrest merged with BMC in 1996.)

In late June that year, two helicopters from Westover landed at Fairview to test the feasibility and safety of the designated 75-foot-wide helipad location. As part of that test, representatives from the Air National Guard inspected the site and found it suitable.

Apparently without consulting town officials, the hospital moved ahead with the project in mid-July, using a bulldozer to clear and level the helipad location in advance of paving it. Several newspaper stories chronicled the Guard’s test flights and described new lights to be installed on nearby utility poles to guide helicopters during night landings.

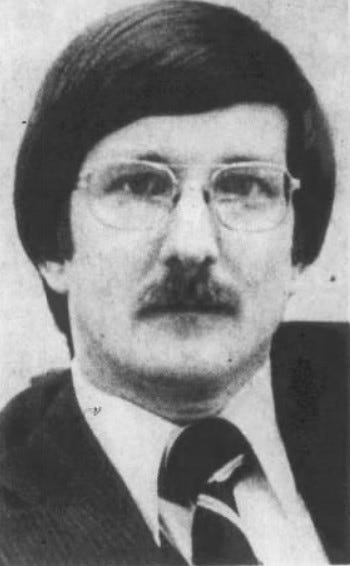

Not surprisingly, the bulldozers were noticed by hospital neighbors. Two weeks later, in response to a complaint from abutter Walter A. Syer, the late publisher of High Fidelity magazine whose son Kurt became a commercial pilot and today helps promote the Great Barrington Airport’s “Fly Friendly” noise-abatement initiatives, the Planning Board got involved. It summoned the hospital’s new 32-year-old administrator, Guy A. Barg, and its attorney, Edward G. McCormick, to the board’s next meeting.

Barg told the Planning Board that work was underway to add more parking and prepare an area for helicopter landings. He and McCormick both assured the board’s members that the new helipad would only be used occasionally to transfer patients in emergencies. They said the Air National Guard’s recent test landings had confirmed the suitability and safety of the location. And in a claim that echoes the airport’s historical habit of not seeking necessary town approvals, Barg and McCormick said they didn’t think they needed any town permits or permission.

The board’s chairman, George R. Osgood, pointed out that the town’s zoning bylaw didn’t allow a heliport in a residential district. Other board members chimed in with the suggestion that medical transfers be made at the airport. They also said that while they wouldn’t object to occasional emergency helicopter landings, they “were against officially designating that area as a landing site,” according to a news account of the meeting.

That informal and perhaps inappropriate verbal sign-off was welcomed. In September, Barg announced the hospital was completing work on the new parking area and would, he told the Eagle, also use it for emergency helicopter landings. “We figure if we have four such landings a year, it’ll be a lot,” Barg said. Non-emergency helicopter landings, if there were any, would be at the airport.

Over the next few years, news reports described occasional helicopter transfers. One flight took a Canaan, Conn. man from Fairview to Boston for surgery to re-attach fingers severed in an industrial accident, but the news account didn’t mention where the helicopter landed. Other stories described New York State Police helicopters meeting ambulances at the airport to bring patients to Albany Medical Center. And a 1981 letter to the editor from a nurse at Fairview said the hospital had utilized Air National Guard helicopters three times as part of the MAST program, but it wasn’t clear if those landings took place at Fairview’s semi-sanctioned landing area, the airport, or somewhere else.

(Fairview Director of Community Relations Lauren Smith and BHS spokesperson Leary did not respond to emails last week asking if Fairview is still considering a helipad.)

The airport versus other landing zones

That history, context, and Fairview’s recent concern about patient-transfer times is important in the current debate about activities at the airport. That’s especially true if ongoing or future legal action were to make the airport temporarily or permanently unavailable. That discussion has included suggestions that helicopter transfers from Fairview are only possible at the airport, which is not accurate.

Communities without a nearby airport still benefit from helicopter air-ambulance flights using non-airport landing zones—like the one used for decades next to BMC. They have designated landing zone locations that are used repeatedly and include parking lots, athletic fields, and parks. In conjunction with air-ambulance providers, fire departments and first responders routinely practice establishing those landing zones.

Still, Belman and Burger both highlighted some advantages of utilizing the airport. The most significant, according to Burger, is that there’s no need to dispatch a fire truck and firefighters. He said the budget impact of establishing a landing zone for each of the 15 transfers a year from Fairview would only be about $5,000, but he said it would still mean using Fire Department resources—particularly his on-call-but-not-full-time firefighters—that today aren’t required. (In a “Coffee with the Town Manager” Zoom conversation last March, Burger said the department responds to about 1,200 calls each year. They’re about evenly split between fire-and-rescue and calls for emergency-medical services, he said.)

The airport also has runway lights that can be activated at night and offers easy access for an ambulance to reach a parked helicopter on the paved—and, in winter, always cleared of snow—tarmac.

If the airport wasn’t available, other locations that Burger suggested could be utilized include three sites on South Main Street, each about a mile from Fairview: the little-used Great Barrington Fairgrounds, the Little League baseball fields at Olympian Meadows, and the parking lot at the Great Barrington Veterans of Foreign Wars post. The first two, at least, might have winter-availability issues if not regularly cleared of snow. “Every [non-airport] location comes with seasonal challenges and times they are in use,” Burger said.

A complex part of a complex health-care system

Belman’s keen awareness of available ground-ambulance resources when considering helicopter transport also points to another little-discussed and potentially important development: the dominance of the helicopter air-ambulance industry by those private-equity-backed companies. Over the last year, in particular, they have faced enormous headwinds from stricter federal regulation of their billing practices, higher fuel prices, labor shortages, low Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates, and climbing interest rates—all of which have dramatically impacted their profits and threatened their highly leveraged, debt-heavy business models.

The significant change to federal regulations addresses the longstanding problem of patients being billed for expensive out-of-network emergency care. Millions of Americans have seen that problem first-hand in the form of “surprise bills” from emergency-care providers—particularly for ground ambulances and helicopters—that do not have agreements with a patient’s private health insurance. That led to passage in 2020 of the No Surprises Act, which now prohibits most of those bills—though ground-ambulance services are excluded from the law’s new protections.

What spurred Congressional action was, in part, the enormous bills received by patients flown by helicopter air ambulances. Those were often for tens of thousands of dollars—and sometimes much more. A major contributor was the dominance of those private-equity-backed providers, who dramatically increased the price of air-ambulance flights while remaining out-of-network for more than two thirds of privately insured patients.

An agreement on federal legislation to prohibit that surprise or “balance billing” was reached among House and Senate negotiators from multiple committees in 2019, but it was scuttled by House Ways and Means Chairman Richard Neal. Neal has been in Congress since 1989 and has represented the Berkshires since 2013. (DISCLOSURE: I was a candidate in the 2012 Democratic Congressional primary that Neal won.)

That derailed, bipartisan bill set allowable out-of-network rates at no more than the median of negotiated in-network pricing for the same service—a crushing blow to providers who were profiting from balance billing that charged patients far more than in-network pricing for the same service.

A longtime recipient of substantial campaign funds from private-equity interests, Neal’s opposition was widely seen as protecting the profits of those providers. Even as he said he was interested in addressing the surprise-billing problem, Neal was criticized by both Democrats and Republicans in Congress for throwing sand in the gears of a popular bipartisan agreement.

In 2020, after House Speaker Nancy Pelosi pressured Neal—he was trying to scuttle yet another bipartisan agreement—the No Surprises Act was passed and signed into law. But since then, Neal has supported efforts to undermine the Biden administration’s rulemaking around one key part of the law: how prices are negotiated between providers and insurance companies for what used to be passed along to patients in those mammoth surprise bills. Neal continues to advocate for regulation that numerous studies have shown will mean higher prices and higher insurance premiums. (Advocates for Neal’s position, including the American Hospital Association, argue the administration’s approach will hurt rural hospitals and providers.)

U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra has adamantly defended the new regulations. In a 2021 interview, just prior to the law’s effective date, he had little sympathy for those providers who benefited from surprise billing at rates far above the regulations’ preference for median in-network prices. Becerra pushed back on the argument that the wildly different rates charged by providers was somehow justified. “It’s not fair to say that we have to let someone gouge us to be in business,” he told Kaiser Health News.

Some policymakers have advanced legislation to increase Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates for helicopter air ambulances, and a working group established by the No Surprises Act recommended the same. But companies like Air Methods have already taken a significant hit from the inability to keep passing on those large expenses directly to patients—or to the patients’ employers and insurance providers. Before and since the No Surprises Act went into effect, Air Methods has shuttered dozens of helicopter bases around the country, including some that served rural areas. Last year it shut down its Hawaii air ambulance service—leaving the islands with only one provider—and several other bases in Texas and Missouri. In 2019, it closed 18 bases in Arizona, Kentucky, South Carolina, Oklahoma, Texas, Georgia, Alabama, and New Mexico.

The perfect storm of industry consolidation by private-equity interests, an overdue end to surprise bills, and rising interest rates on Air Methods’ significant debt load may mean more trouble ahead. Air Methods has already seen profits decline: In the second quarter of last year, after the No Surprises Act took effect, its earnings dropped almost 60 percent. That highlights the high costs that were previously being paid by insurance companies, employers, and those patients who received large surprise bills. Last November, Moody’s downgraded its rating of Air Methods’ outstanding debt and pointed to what it called the company’s “increasingly unsustainable” and “untenable” capital structure. It highlighted $1.25 billion in debt obligations that come due in April 2024, “further weaken[ing]” its liquidity, and warned that Air Methods’ “earnings and margins will remain stressed.” (Moody’s also downgraded the debt of Global Media Response, the other large private air-ambulance provider, and changed its overall outlook on that company to “negative” from “stable.”)

These mounting challenges for Air Methods are significant for the Berkshires. The helicopter air ambulances typically called for emergency transfers from Fairview and for on-scene evacuations of accident victims are all connected to Air Methods: The Hartford HealthCare LifeStar critical-care helicopter service utilizes pilots and mechanics who are Air Methods employees; a LifeStar helicopter and crew based at Westfield-Barnes Regional Airport is a partnership between Hartford HealthCare, Baystate Health in Springfield, and Air Methods; and the third primary air-ambulance option, LifeNet of New York, which serves Massachusetts and other nearby states, is also owned by Air Methods. Even the UMass Memorial Life Flight helicopter sometimes seen in the Berkshires is owned by Air Methods.

In the end, regardless of whether they land at Great Barrington Airport, at the scene of a devastating accident, in the parking lot at Wahconah Park next to BMC, or at a landing zone set up by a local fire department, helicopter air ambulances are a crucial part of rural health-care delivery. That’s why these industry rumblings present a growing local and national risk: It may turn out that having two-thirds of a vital, lifesaving industry—staffed by thousands of talented pilots, critical-care nurses, and flight paramedics—owned by two Wall Street investment groups is not so good for our health.

Times certainly have changed. When UMass Memorial launched its groundbreaking helicopter service in 1982, the price was a little more reasonable: Patients paid just $100—plus $4.00 per mile traveled.

NEXT: In part six, the history of a noisy airport debate.

∎ ∎ ∎