As Berkshire Aviation Enterprises goes in front of the Great Barrington Selectboard for the third time seeking release from zoning restrictions, a contentious community discussion is again underway.

∎ ∎ ∎

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Heather Mutterperl, who lives in midtown Manhattan and works in real-estate finance, escaped the uncertainty and stress of a city in lockdown by renting a house on Hurlburt Road in Great Barrington, a stone’s throw from the Walter J. Koladza Airport.

Named for a Connecticut-born World War II-era test pilot, who ran the airfield for 60 years, and known to pilots by its station code “GBR,” Great Barrington’s is a privately owned public-use airport that has operated in a residentially zoned neighborhood at varying levels of intensity since the early 1930s.

With a couple dozen Cessnas, Pipers, and other aircraft largely from the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s tied down in rows next to a 2,579-foot paved runway, and another couple dozen housed in aging, open-front hangars, it has the look and feel of airfields and aviation from an earlier age -- something its owners, advocates, and fans say is among the reasons it’s worthy of preservation and protection.

Settling into her rental, Mutterperl couldn’t avoid the frequent sound of mostly single-engine piston aircraft flying just overhead. “My house was in the flight pattern,” she told me one morning last June, referring to the primary landing approach from the east. It takes pilots, at that point just a few hundred feet above the ground, over some houses on Hurlburt Road and across one of farmer George Beebe’s corn fields before touching down on Runway 29, mere feet beyond Seekonk Cross Road.

“Every time I heard one of those planes,” she recalled, “I’d run out to the backyard to go see what was happening.”

Mutterperl had never been to Great Barrington before the summer of 2020. When she first arrived, she also didn’t know anything about the controversy swirling around Town Hall at that very moment: Berkshire Aviation Enterprises (BAE), the owner and operator of the airport, had just applied to the town’s Selectboard for the second time in three years for a special permit that would allow -- if the Planning Board also signed off -- construction of six new aircraft hangars. They would keep 33 planes out of the harsh Berkshires weather, the airport’s management said, and were vital to its solvency. BAE planned to charge perhaps $400 per month to store each plane, far more than outdoor tie-downs.

Crucially, the application also sought permanent release from longstanding zoning restrictions meant to protect the residential neighborhood where the airport is located. It would bring the airport into conformance with a bylaw provision that allows an “aviation field, public or private, with essential accessories” to operate in one of the town’s two R4 residential-and-agricultural zones, but only after a thumbs up from four-out-of-five members of the Selectboard. With that permanent change, which runs with the land in perpetuity, the airport could build its hangars and make other changes and expansions largely by right.

But, until 2017, it had never sought such recognition under five different ownership groups dating to 1929, when wealthy local businessman Robert K. Wheeler and a group of town heavyweights purchased a former onion farm on what was known as the Egremont Plain.

A basic tenet of zoning law limits the growth of such “preexisting nonconforming uses” that were already in place when the town adopted its first and subsequent zoning bylaws -- temporary restrictions approved by voters in March 1931, permanent rules a year later, and various updates and changes since. That status has stood in the way of a vision for the airport expressed by the current owners in various ways, including in media interviews, since inheriting the airport from Koladza’s estate after his death in 2004.

After a tumultuous four-year probate battle with Koladza’s brother John that’s documented in a thick file at the Berkshire Family and Probate Court in Pittsfield, three pilots and an aircraft mechanic, all long associated with the airport, formally took over in 2008. As they would soon learn, it was both enormous good fortune -- they didn’t know Koladza planned to bequeath them a valuable property -- and also bad luck, as the airport’s problematic zoning status would soon challenge their plans.

While Mutterperl was settling into life in Great Barrington in the summer of 2020, others living near the airport -- and further afield in surrounding towns in the southern Berkshires and Columbia County, New York -- noticed what they said was a substantial increase in flight traffic from GBR. According to the airport’s owners and management, it was due to the influx of people during the pandemic and others who now had time to learn to fly at BAE’s respected flight school. Some traffic was also from pilots just enjoying something that was allowed amidst the many restrictions of a global public-health crisis.

Advocates for the airport have long argued there was not much of an increase, suggesting either it was just a temporary bump or a product of perception: People were home 24/7, they told me, and more aware of roughly the same number of overhead planes. Neighbors disagreed and complained bitterly to airport staff and the Selectboard about the intensity of operations and increased disturbance, particularly from the flight-school aircraft. (An examination of these claims appears later in this series.)

(DISCLOSURE: I live in Alford, Massachusetts, approximately four miles northwest of the airport. I occasionally see or hear aircraft flying to and from the Great Barrington Airport.)

Regardless, its owners and supporters argue that over its history the airport was at times far busier. Like when it trained pilots entering military service during and after World War II, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and especially during in the mid-to-late 1970s, when a post-Vietnam update to the GI Bill helped fund pilot training during a popular time for general aviation.

Yet today’s airport critics, including those who have lived near the airport for decades and in some cases generations, point to the town’s zoning bylaw. They argue that what matters is not the increase in flight activity of the last few years, or changes since new ownership took control in 2008, but what’s grown up at the field since its dedication during a three-day aviation festival in September 1931: Change, expansion, new buildings, and growth in operations they say should never have been allowed. At least not without town boards weighing in as required.

They also suggest Walt Koladza did a better job respecting the neighborhood than BAE’s current owners and staff. They compare what they call Koladza’s “hobby airport” -- a misnomer, based on decades of news coverage, particularly from the 1940’s through the 1970’s -- with what they say are BAE’s recent efforts to “monetize” the airfield. (Jim Jacobs, a minority partner in BAE, told me last summer that “we don’t make any money” and said the owners write checks each year to cover shortfalls.)

While the issues involved may be complex, the airport critics’ bottom-line argument is simple: Just as every property owner in Great Barrington is subject to the zoning bylaw, so too is the airport. And that’s true even if generations of town officials looked the other way, they say. Or simply never knew about the airport’s restricted status. Moreover, nearby property owners say they are taxpayers who have every right to expect the zoning bylaw will be enforced to protect enjoyment of their properties. And that in recent years, things have gotten out of hand.

Their concerns go beyond increased noise and nuisance in that R4 residential-and-farming neighborhood, of which the airport’s roughly 90-acre property is only a small part. Since 2017, they’ve raised other objections. They point to the airport’s safety record, noting recent and not-so-recent crashes near their homes and an increase in the number of student pilots. And environmental concerns like exhaust from leaded aviation fuel, hazardous materials involved in aircraft maintenance, and the risk from the airport’s 20,000 gallons of fuel stored in an underground tank just a few feet above the aquifer that provides much of Great Barrington’s drinking water. (The Board of Health last week forwarded these same environmental concerns to the Selectboard for consideration.)

Ultimately, they say benefits to the town from the airport -- from tax revenue to jobs to any economic boost -- are minimal. And certainly don’t balance the negative impacts from something they say serves a small group of people, many of whom don’t live in Great Barrington.

The flight school gets busier

It’s not surprising that student flights contribute to a significant portion of the airport’s activity. The focus of BAE’s business has long been high-quality, personally tailored flight instruction, along with a respected FAA-certified maintenance shop, revenue from aircraft tie-downs, rentals of existing hangar space, some charter flights, and informal aircraft sales. The activity in each of these areas has varied dramatically over the years, with developments and growth at the airport reflected in abundant news coverage in The Berkshire Eagle and weekly Berkshire Courier since the 1930s.

In 2020, majority owner Rick Solan had just retired from a 37-year career at American Airlines, where he spent most of it as a skilled Boeing 777 “check airman” -- riding along with other pilots to train and certify them on the massive jumbo jet, which can carry more than 350 passengers. Aviation is in his blood: His father was an Air Force mechanic who worked on B-17 bombers and the P51 Mustang long-range fighter and later took his young son to watch airplanes at Bradley Airport near Hartford. Solan also has extended family with roots in the aviation community around Canaan, Connecticut, where he grew up and still lives.

His decades-long passion for teaching the next generation of aviators means he’s at the airport for long days of instruction at the busy flight school, in addition to his general oversight of the operation. Solan’s wife Dena died in late 2019; he told me during our first conversation last summer that he’s since spent nearly all his time at the airport, arriving most days by 6:30 a.m. and often still there into the evening.

But what’s good for the goose was not good for the proverbial ganders living nearby. Just down the street from Mutterperl’s Hurlburt Road rental, a 60-year resident of that street complained to BAE staff about increased traffic and noise that frequently continued into the evening during that first pandemic year. He soon received a cease-and-desist letter from the airport’s attorneys after what he concedes was a heated conversation in the airport’s office.

At least one other family received a similar attorney’s letter: Full-time residents of Egremont whose home atop Baldwin Hill is directly under the flight pattern used by student pilots during continuous takeoff-and-landing practice. That can mean repeat overflights at just 500 to 1,000 feet above the ground every eight or nine minutes for hours on busy weekend days. And sometimes more frequently if multiple student pilots are in the pattern.

Last July I spoke to that family at their Egremont home. BAE planes flew nearby and directly overhead every few minutes for most of an hour. With the windows open on that warm summer day, we sometimes had to pause our conversation until the noise subsided. The Egremont residents said that for the five years before the pandemic, they hardly noticed the occasional overflights. They and others also complain that the aircraft sometimes violate the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) requirement that pilots flying in “sparsely populated areas” maintain at least 500 feet between their plane and “any person, vessel, vehicle, or structure” as they pass nearby or overhead.

“This firm represents Berkshire Aviation Enterprises,” one of the letters began. “It has come to our attention that you have been engaging in repeated, unwanted communications toward Berkshire Aviation, including by making multiple phone calls. We hereby direct you to cease and desist from any and all further communication or contact with Berkshire Aviation.” The letters, signed by attorney Christopher M. Hennessey of the Pittsfield law firm Cohen Kinne Valicenti & Cook, concluded, “Going forward, please direct all communications to this firm.” (The letters do not have the force of law.)

Jacobs, the airport’s co-owner, told me last summer that letters were sent because phone calls and interactions had become heated, with people sometimes yelling and cursing at BAE staff. Hennessey declined to comment on specific reasons for the letters or the number of people who received them.

The airport’s owners and flight instructors also dispute claims of low flights and told me they do their best to send some takeoff-and-landing training to nearby airports in Hudson, NY, Pittsfield, and elsewhere. And that in Great Barrington they try to limit it to students preparing for upcoming licensing exams. They say they scold pilots who fly unsafely or out of the flight pattern. They also try to limit intensely local takeoff-and-landing training in the early morning and evenings, something they’ve proposed enshrining in special-permit conditions.

Complaints increase in 2020

Many others, including other airport neighbors who had never previously complained about its operations, spoke out that summer at the special-permit hearings in front of the Selectboard. They told the board about their fear that new hangars and a special permit would just make things even worse.

At an August 24, 2020, Zoom hearing, James Fingeroth, who has owned a home on Hurlburt for 40 years, complained to the board about traffic, noise, and flight paths that were “increasingly disruptive and increasingly ignoring the needs and concerns of the residential neighbors around the airport. We see this, unfortunately, virtually every day, especially on weekends,” he said.

A Seekonk Cross neighbor, Alex Johnson, told that board that “a small nuisance has been tolerated for many, many years, but there's a threshold when it becomes a larger nuisance and when it becomes a danger to health and well-being."

By contrast, pilots -- many from outside Great Barrington -- and other airport advocates told the Selectboard stories of the experiences and opportunities the airport provides to the community: From learning to fly and pursuing a career in aviation, to attracting visitors valuable to the town’s tourism-based economy, to serving as a landing area for medical-transfer helicopters, to hosting popular Bike-N-Fly fundraising events for Rotary Club scholarships.

It was largely a repeat of the complaints, concerns, and advocacy expressed at contentious in-person hearings in 2017, when BAE abruptly withdrew its application in the face of strong opposition. In 2020, pandemic restrictions relegated the hearings to Zoom as opposed to a packed Town Hall hearing room, perhaps moderating tempers.

To address environmental worries, soil and water testing done by the airport in 2017 and shared with the Selectboard showed normal background levels of lead, the owners said. Its on-site well-water similarly tested without actionable lead levels, and a new double-walled-and-monitored underground fuel-storage tank was installed in 2018. Testing for lead in 2018 and 2021 by the Great Barrington Fire District, which draws water from an aquifer at a location 1.2 miles northeast of the airport’s underground tank, just off Hurlburt Road, found levels below state and federal limits for safe drinking water. (The airport sits on top of the aquifer and is located in the town’s Water Quality Protection Overlay District.)

Still, after several months of public hearings and board deliberations, the Selectboard voted unanimously to deny the special permit. It noted in its findings that “growth at the airport beyond its current level of use and type of operations including types of aircraft could further detract from the rural, residential, and agricultural character of the area.” The board pointed to the town’s 2013 Master Plan which, referring specifically to the airport, says, “… any activity, growth or development here must be regulated to protect the town’s water supply, and to ensure uses are compatible with residential and agricultural neighbors.”

To those upset about the airport’s intensity of operations, the denial was welcome news. But it didn’t result in any changes. Indeed, all evidence is that the airport and its flight school have become even busier than in 2020.

The zoning-enforcement request

Today, some families that received cease-and-desist letters are listed in court filings as supporters of legal action that has, since November 2021, sought zoning enforcement by the Town of Great Barrington. They want the town to limit the airport’s operations to a level commensurate with what they say is allowed for a preexisting nonconforming use. (Claims that the action was initiated when the airport sought to rebuild its office are not accurate.) Interestingly, several of them told me they don’t want the airport to close. They just want to rein-in operations they say have become unbearable.

Ellen House, who has lived on Hurlburt Road since 1985 (her husband Geoffrey, who until recently operated a trash-hauling business and was among those who received a cease-and-desist letter, has been there since the early 1960s), told me last week, “I really don't want to see the airport go away.” But she pointed to the intensity of flight school operations as the driver of activity that has, she said, made it difficult to even enjoy being in her yard on a nice day. She and her husband told me they want the airport to return to a lower level of activity.

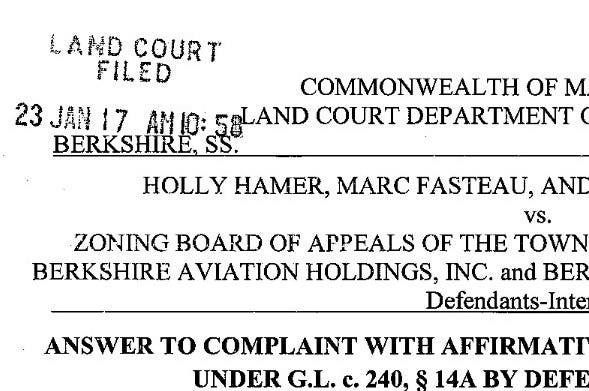

On February 1, 2022, Building Inspector Ed May formally denied the enforcement request, pointing to a Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) decision in 2017 that called the airport “a legal preexisting nonconforming use,” and writing, “I do not find any clear violations of the Zoning Bylaw in the use of the property.” Last April, the ZBA unanimously backed May’s decision. In May 2022, the neighbors appealed to the state’s Land Court, claiming that both the building inspector and ZBA ignored the facts and misinterpreted the law.

The plaintiffs in the case, longtime Seekonk Cross Road residents Holly Hamer, Anne Fredericks, and Fredericks’ husband Marc Fasteau, argue that not only has the airport expanded its operations far beyond the level of its 1932, pre-zoning use as a grass field with a handful of planes, but that it added buildings, hangars, a paved runway, and substantially increased its operations without seeking necessary town permissions -- as owners of any preexisting nonconforming property must do. Of the structures on the property, only the original 1931 hangar was issued a building permit, according to town records.

Over 90 years, even as many areas of Great Barrington were re-zoned to create new business districts, the zoning of the area that includes the airport has steadily shifted toward promoting more residential and agricultural use, not less. And as explored later in this series, amidst a decades-long trend toward re-zoning areas of town for business and industrial use that lasted into the early 1970s, a new restriction applicable to the location of airports -- or, perhaps more accurately, the airport -- was added to the zoning bylaw in 1960.

The details of the Land Court case are critical to understanding the airport’s urgent third attempt to secure a special permit to be permanently recognized as an aviation field. Airport attorney Dennis Egan, also of the firm Cohen Kinne, told the Planning Board in January that the goal of the application filed last month is to “lock in” current operations as legal and thereby protect the airport’s “existence.”

Yet even as it seeks a special permit, the airport has told both the Planning Board and the Land Court that the airport can’t legally be constrained by the town’s zoning bylaw. “It’s our argument before the Land Court that we’re actually exempt from zoning,” Egan told the Planning Board, which is responsible for writing and implementing the town’s zoning rules. No member of the board challenged that not-insignificant claim. Nor was it included in the detailed minutes of the meeting.

After asking a few questions of Egan and Solan, hearing from airport supporters -- there were no speakers in person or on Zoom who spoke out against the application -- and engaging in some brief discussion, board members voted unanimously to recommend approval by the Selectboard.

The board went further: It endorsed a suggestion from Assistant Town Manager Chris Rembold that the Selectboard revisit that 1960 restriction, known as section 7.2.1.1. The airport’s special-permit application devotes several pages to it, arguing with case-law citations that the Selectboard should ignore it. The provision requires that an aviation field “be so located that it is not likely to become objectionable to adjoining and nearby property because of noise, traffic or other objectionable condition.”

A week later, the airport’s attorneys preemptively told the Land Court that they plan to appeal any Selectboard denial -- or even an approval if it contains “conditions the [airport] cannot live with.” If they don’t get a special permit on their terms, they told the judge, they’ll continue to argue that the airport is exempt from the zoning bylaw. And further, that state and federal law blocks the town from regulating the airport and its property.

Those arguments are certain to be litigated vigorously. “We just think there’s a more practical and reasonable approach,” Egan told me in an interview earlier this month. He said their arguments are logistical -- asking the court for a delay while the special-permit process plays out -- and also appropriate, in that the airport is seeking a fair resolution while “arguing the alternatives” in court.

Earlier, on January 17, the airport filed legal action against the Town of Great Barrington challenging the validity of the town’s entire zoning bylaw. That filing in the Land Court case is known as a counterclaim; it was met a few weeks later with responses from both Town Counsel David Doneski and an attorney for the plaintiffs, Thaddeus Heuer of the firm Foley Hoag, disputing the airport’s argument. (Town Manager Mark Pruhenski declined to comment on the airport’s claim against the town.)

Hennessey, the other airport attorney, told me in an email that despite the counterclaim filing and argument that zoning doesn’t apply to the airport, “We think our interests and the town’s interests are aligned.” He said that BAE’s involvement will help reduce the town’s legal expenses, even with money spent to have Doneski defend against the counterclaim.

Hamer, a plaintiff in the case who according to real-estate records has owned her home next to the airport since 1997, told the Selectboard in both 2017 and 2020 that she doesn’t oppose the existence of the airport, just its expansion. For 20 years, she said, had no complaints. “I had never complained about noise from the airport. And the reason is that there wasn’t much noise, there was very little disturbance and there was mutual respect when Walt [Koladza] was the owner,” she told the board in 2020.

She’s not new to town -- by a longshot. In the 1970s Hamer worked as a VISTA volunteer at a human-services center in Great Barrington and as a counselor at the Women’s Service Center of Berkshire County in Pittsfield. She is a longtime library booster as an elected member of the Library Trustees and as leader of Friends of the GB Libraries. Following the 2017 battle over the airport’s hangars-and-special-permit application, Hamer ran unsuccessfully for the Planning Board in 2017 and the Selectboard in 2018.

A businessperson, community volunteer, and women’s rights activist, Hamer’s focus has long been what she sees as the airport’s expansion plans. And she doesn’t believe the owners are serious about addressing neighbors’ concerns. “BAE has tried to pit the neighbors against the community, claiming we are anti-airport instead of just anti-major expansion,” she wrote in an e-mail to Selectboard members on August 4, 2020.

She warned that a special permit would “open the floodgates to many many [sic] more ‘accessory structures’ than the six [hangars] in the current proposal.” She concluded with context: “This issue has a much wider effect than just a few neighbors or a few hangars for that matter. It concerns our caretaking of natural resources, our neighborhoods, how we treat each other and our vision for the future.”

(Hamer declined a request to be interviewed for this series.)

Jacobs, who became a minority partner in BAE a few years ago, told me in an interview last July that the airport tries hard to abate the noise and respond to complaints while still maintaining safe operations. But he said there’s only so much they can do. “We’re an airport. I can’t stress that more to anybody who is upset about the noise. We’re an airport. That's what we do,” he said. “I take a harder line on the people who say to me, ‘Oh, well, you know, it's really noisy.’ I say, ‘Yes, and I’m sorry for it, and I apologize to you. And if I can help you in any way, I will help you.’ But we are an airport. We do make noise.”

Like others, he pointed to small adjustments in the traffic pattern he says are more considerate to close-in neighbors, like raising the pattern’s downwind-leg altitude by 250 feet. That coincided with a 2018 recommended FAA directive to standardize the pattern at non-towered airports at 1,000 feet above-ground-level. (Under previous FAA guidance from the 1990s, it was a less-specific 800-to-1,000 feet.) Like many others, Jacobs also said there was more activity in the past. “When I trained here in the 70’s I did thousands of takeoffs and landings at Great Barrington Airport. I mean, that's all I did was take off, take off, take off, and everybody else did that,” he said.

A different reaction to low-flying planes

Mutterperl, the temporary transplant from New York, had a somewhat different reaction to the frequent sound of machines flying overhead during the summer of 2020: She began spending time at the airport watching the planes come and go. She wasn’t alone: During that first pandemic summer, the airport became a popular place not just for longtime pilots and wannabes to take to the air, but also for those looking to escape the drudgery of lockdown by spending time with others in a safe, outdoor location.

She told me that at first, she didn’t go inside the pilot’s lounge, a room with two leather couches and a large wood table, its walls covered with flight memorabilia from pilots and flight-school students. There’s a large picture windows that looks out toward the runway. It has the feel of a small-town post office: People and pilots come and go, sometimes settling in to talk aviation with friends, student pilots, BAE staff, and travelers passing through. It’s located inside the small, one-story building on Egremont Plain Road originally constructed as Walter Koladza’s home, likely in the late 1940s. And she never spoke to Solan or his son, Joe, the 24-year-old flight instructor and longtime GBR fixture who is soon heading off to the airlines. (Joe Solan has been the airport’s operations manager since 2018.)

“Then one day, a light bulb went off and I said, ‘Hey, maybe I could do that,’” Mutterperl told me. She talked to the Solans and on August 4, 2020 -- she remembers the specific date -- went up for her “discovery flight,” an introductory $99 excursion that gives prospective students a chance to learn the basics of pre-flighting an airplane for safety and then, with an instructor at duplicate controls in the right-hand seat, actually fly a plane. “I thought it was fascinating,” she said, describing her early lessons in the air and, during ground training, “getting totally geeked-out on the science behind flying. I thought that was amazing.”

As she continued her training, which, after moving back to Manhattan required frequent two-and-a-half hour drives north, Mutterperl said she got to know the community of pilots at GBR. “I absolutely love the spirit at this airport,” she told me. “Every plane here, the people have a story. Some of them that live here really contribute to making the Great Barrington community a community.” She described Rick and Joe Solan as “salt-of-the-earth, like the owners that you want for all your local businesses.”

On that early summer day last year, we were sitting at a picnic table at the airport. Mutterperl was about to meet Rick Solan for a lesson and continue preparations for an upcoming private-pilot examination. I was there to learn more about the airport, its owners, the local aviation community, and the issues long creating turbulence. And separately hear from airport critics, municipal officials, aviation experts, environmental activists, lawyers, historians, and others with views on the airport and the broader context of Great Barrington over the life of the airport.

The battle over the airport has continued to escalate since BAE first went before the Selectboard in 2017, expecting to get quick approval for plans that a former airport manager, retired United Airlines pilot Ken Krentsa, told me they thought would be cheered. But as soon as they presented their vision at a meeting with neighbors -- meant to show transparency and collaboration, Krentsa said -- it was clear they had miscalculated.

This Berkshire Argus series is an examination of what happened before 2017 and since, presenting the perspectives of people on all sides of a matter that will, once again, come to a head in Selectboard hearings. It’s a product of more than 75 interviews, dozens of public-records requests, archival research, time spent at the airport, and talking with key players on all sides.

Fasteau, an attorney, writer, and venture-capital investor, and his wife Anne Fredericks, an artist, designer, and former Wall Street professional, spent more than a dozen hours telling me about concerns they’ve expressed publicly since that first 2017 meeting at the airport. As I’ve learned since first meeting them last September, their focus is as much on environmental issues as anything else; that follows on from decades of environmental activism on matters local and further afield, and that culminated in their Land Court action alongside Hamer. They also told the Selectboard in 2017 that actionable lead levels found in their private-well water could only come from the airport, though they concede there is no definitive evidence of that link.

Fredericks insists the goal is not to shut down the airport. Rather, she wants it to return to “hobby airport” status to protect the town’s water supply and the community that lives along the Green River. Pointing to a November letter she sent to the Selectboard, which was adapted for the “GB Airport Facts” website launched this month, she told me in December, “This is about our water. This is about our community. This is about the wildlife … this is about the free ability of people to enjoy their property,” she said. “It’s a community issue for us. And because no one was doing anything to stop the expansion, we stepped into the breach. Because it’s really egregious.”

Still, airport advocates told me they see the Land Court case and other efforts as a six-year, “throw-everything-at-the-wall” strategy to close it down entirely. On social media, some of those advocates argue without evidence that Fasteau, who with Fredericks is part owner of luxury hotels in St. Barth’s and Lake Como, Italy, has a plan to acquire the airport for nonspecific “redevelopment.” They hint it’s for a luxury hotel – even though hotels are prohibited in the R4 zoning districts.

Fasteau and Fredericks both strenuously deny any interest in owning or developing the airport property. "I can just categorically tell you no, not ever, for 1,000 reasons," Fasteau told me in September.

Since that first visit to the airport last summer, I’ve also talked to pilots for major airlines who grew up or learned to fly at GBR and who told me about their experiences in aviation. (It was surprising to learn how many are afraid of heights, at least when not in the cockpit.)

That includes Justin Ward, from the family that’s owned Ward’s Nursery in Great Barrington for 65 years, who flies the 737 out of the New York City area for Delta Airlines. And pilots like Jason Archer, a passionate science educator from Connecticut who is GBR’s chief flight instructor. He’s an astronomer, yoga aficionado, and outspoken advocate of strategies to improve flight instruction to produce better, safer pilots. And Noah and Ari Meyerowitz, owners of the Great Barrington-based Sprout Brothers, who are carrying on their father’s legacy in both business and local aviation.

I also met Peggy Loeffler, a beloved GBR flight instructor and designated FAA pilot examiner who has championed the training of women pilots at GBR for decades -- even after being turned down for a job by Koladza in the mid-1990s. She said that back then there were no women at the airport. “I went to Walt and said, ‘Walt, if I train here with my scholarship money, can I have a job teaching when I’m done?’ And he said, ‘Nah, I don’t think so, kid,’” Loeffler recalled in a conversation in September. “Because he had his boys’ club. I guess he didn’t picture having a female instructor.” (She was hired at GBR after Koladza passed away.)

That might seem curious given that Koladza’s wife Louise was also an accomplished pilot. And according to many I interviewed, including Loeffler, there was an understanding that she was the one who really ran the show at the airport. (Louise Koladza died in 1975.) Few dispute the place long had a heavy “The Right Stuff” male tilt: The airport’s rowdy crew of KB’s, or “Koladza’s Bastards,” a local version of an international pilots’ fraternity known as the Quiet Birdmen, went on regular guys-only outings to local watering holes and held raucous parties in the long-unused, frozen-in-time basement lounge of the building that now serves as the airport’s office.

Loeffler’s training was financed largely with scholarships awarded by the international women’s organization The 99s, founded by legendary aviator Amelia Earhart on November 2, 1929 -- seven months to the day after land on the Egremont Plain was purchased by Wheeler’s investor group to create the Great Barrington Airport.

Other critics of the airport, including a number who signed on to the Land Court action, spoke to me about their experiences and concerns. In addition to ongoing complaints about increased activity at the airport, some are worried about how contentious the discussion has become; some report feeling intimidated by airport defenders. Several showed me logs and notebooks filled with dates, times, and tail numbers of planes and helicopters they say violated flight rules. And which, they claim, have sometimes intentionally targeted them for harassment-from-the-air.

BAE owners, staff, and local pilots all deny that anyone would target an airport critic with low flights or other harassment, arguing that would only add to the airport’s woes. Still, flight instruction does include so-called ground-reference training that uses landmarks like houses and barns in less-populated areas. That can be annoying and even infuriating to people living nearby. It also includes simulated engine-out drills, which even at safe altitudes and with an experienced instructor on board can be frightening to non-aviators on the ground. (How BAE communicates with those who complain is examined later in this series.)

I also spent time at the airport drinking early-morning coffee with majority owner Rick Solan, a man in his late 60s who speaks about aviation with the rushed, words-running-together excitement of a young pilot newly enthralled with the miracle of flight. Solan gave me access to the airport and its staff and answered every question I asked. He told me last fall that he knows some parts of this story may not be flattering. “I may get some egg on my face,” he said more than once, noting what he called “the sins of the [airport’s] past” and for things he may have mistakenly overlooked. It was a show of transparency that airport boosters say is ever-present with Solan but which critics say is a mirage. They point to inconsistent statements over the years by the airport’s owners, staff, attorneys, and pilot supporters as the root of their suspicions about the airport’s future plans. (Solan concedes that he has made mistakes but told me he’s never intentionally said anything meant to mislead anyone.)

Suspicion and misinformation

Indeed, mutual suspicion and questioning of motives has been rampant in the airport debate. It’s driven by a mix of carelessness, lack of information, vehement and passionate advocacy, and extremely strong emotion. In some cases, that’s led to vitriol and the sharing of provably false misinformation -- sometimes personal -- on all sides. For example, one otherwise thoughtful Pittsfield pilot has long used heated social-media rhetoric in defense of the airport, posting frequently on the Great Barrington Community Board, a Facebook group with nearly 14,000 members. Until Solan asked him to stop, he repeatedly referred to Fasteau as “a billionaire oligarch” and compared him to terrorists like Hamas and associates of Russian President Vladimir Putin. He’s also attributed fake quotes to Fasteau in posts that advance a false narrative meant, presumably, to rile up supporters against the airport’s concerned Great Barrington neighbors.

That at least some acrimony is driven by those outside of Great Barrington is not surprising. The nature of an airport is to attract people from near and far, and many if not most of the pilots, students, and staff at GBR are residents of other towns and states. And there’s long been an unproductive feedback loop of claims and counterclaims, accusations about motives and charges of hypocrisy, NIMBYism versus lifesaving medical airlifts, and kids learning to fly versus danger to the town’s water supply.

The rhetoric in the coming weeks is likely to again become hyperactive and hyperbolic. Indeed, a recent letter to the Eagle from a pilot in Virginia noted that the airport trained pilots during World War II and warned darkly that the Selectboard “must answer for how it protects America’s anti-fascist legacy if it chooses to restrict the airport.”

It’s not the first time that fiery words, misinformation, personal attacks, and accusations of intimidation have swirled around the Great Barrington Airport. Today it’s fueled by longstanding gaps in the community’s knowledge of the airport and its history, misunderstandings about aircraft and flight training, the intricacies of zoning and the law, and a host of other issues. To say the issues are more complex than the oft repeated, “Didn’t they know there was an airport there?” is a monumental understatement.

What’s true, however, is that airport supporters have not focused on rebutting complaints about flight intensity or zoning violations. Instead, they’ve appealed to the community to “save the airport,” which they argue requires quick approval of a special permit. They’ve gathered petition signatures, highlighted the use of the airport for emergency-medical transfers, promoted the vocational-training opportunities provided by the flight school, sent emails to the Selectboard that share memories of the airport, and argued that critics don’t have their facts straight about flight patterns, environmental dangers, and other issues.

For example, Fasteau and Fredericks have long argued that few planes based at GBR can use the 94-octane unleaded aviation fuel available at the airport, and that older planes won’t be able to use a new 100-octane unleaded fuel. They also suggest eliminating lead remains years away and that older planes will require extensive modifications to use unleaded fuels.

In fact, efforts underway to produce and distribute an unleaded “drop-in replacement” for 100-octane leaded avgas are, at long last, proceeding at a rapid pace with growing industry and regulatory support. The first, developed by Oklahoma’s General Aviation Modifications, Inc. (GAMI), was certified and approved by the FAA last September for “fleet-wide use.” The company expects to have some available next year, initially for flight schools. GAMI’s G100UL fuel works in any piston-engine aircraft.

This new fuel is different than the Swift 94-octane unleaded offered alongside leaded avgas at the airport today; perhaps 60 percent of piston-engine aircraft can use 94UL, but not those with more powerful high-compression engines. (Efforts to replace leaded avgas and the environmental concerns raised locally around its use and storage are explored later in this series.)

The airport’s advocates have made some inaccurate claims of their own. For example, the “Save the Great Barrington Airport” website seeking petition signatures has claimed since last fall that “the judge has recommended [sic] the airport seek a Special Permit to make it a conforming-use and effectively voiding the lawsuit,” presumably to give the application the imprimatur of the Land Court’s Chief Judge, Gordon H. Piper, who is presiding over the case.

Based on filings in the case and the court.fm recording of last June’s case-management conference that I attended via Zoom, that claim is not true. It would be surprising, to say the least, for a judge to recommend in open court how one party might circumvent a legal proceeding over which the judge is presiding. At best, it’s a misunderstanding of a colloquy between judge and attorneys. At worst, it’s a purposeful misrepresentation.

Contacted in December, Erika Gully-Santiago, a court spokesperson, said that Judge Piper would not comment on the petition's claim. “The court cannot comment on a pending case,” she wrote in an email.

(UPDATE: Several hours after this story was posted, the website language was changed from “the judge has recommended [sic] the airport seek a special permit...” to a new inaccurate reference. It now quotes the judge saying a special permit would create “no cause for action” and make the lawsuit “moot.” Based on the relevant discussion from the court.fm audio of that June 15, 2022 hearing, linked here, neither was said by the judge during a conversation with the attorneys to establish the facts of the dispute. The airport’s attorney, Christopher Hennessey, told me in an email earlier this week that his firm does not represent the “Citizens Committee to Save the Great Barrington Airport.” The website also now includes a disclaimer that the group is “not directly affiliated with the airport ownership or airport management.”)

An airport-defending ‘conspiracy’?

When questions of the airport’s growth and level of operations come up, advocates for the special permit have largely fallen back on suggestions of poor record-keeping by the town and that the airport was busier at other times. Any construction was done -- and planes were flying -- in plain sight, they told me. Indeed, the ZBA made that part of its argument last April when it rallied to the airport’s side with conclusions now being litigated in Land Court.

With that special permit in mind, airport advocates argue the question is not what’s happened in the past but what the Select Board can do to protect the airport today and in perpetuity.

For there to have been no town permits or approvals, “it would have to be a conspiracy over generations,” longtime pilot and real-estate investor Richard Stanley told me a few days before Christmas as we talked with Jacobs in the airport’s pilot lounge. Jacobs agreed. Countless Select board and ZBA members, building inspectors, and others would have to be “in on it,” they suggested.

While a star-chamber-like, airport-defending conspiracy seems unlikely, there’s ample evidence that the airport was born and raised by a series of influential owners deeply embedded in the town’s business and municipal affairs. Combined with the community’s fascination with early aviation, and the enormous local impact of World War II, a list begins to form of factors that may explain why it was able to sidestep various zoning-bylaw requirements over many decades.

Indeed, detailed stories of heated battles over zoning changes, requests for variances, and board permissions of the kind the airport would have needed have long filled the local newspapers -- particularly in those first few decades after 1932. Yet it wasn’t until 1990, nearly sixty years after zoning took effect, that the issue of the airport’s preexisting nonconforming status -- that might limit its operations -- emerged. (That 1990 matter will be explored later in this series.)

In an interview last June, Stanley, who lives in Egremont and keeps a twin-engine Cessna 340 at the airport, pointed to news coverage of the airport as evidence that permits and permissions must have been obtained. If all the town’s records related to the airport are missing, it’s the result of different requirements for retaining records years ago, he suggested. “My sense is that everything that’s happened at the airport, everybody in town knew about it, all the time,” he told me.

In its early years, the airport’s interests were advanced by Wheeler, among the most significant residents of Great Barrington during the first half of the 20th century. He and other members of the influential South Berkshire Chamber of Commerce (initially the Great Barrington Chamber of Commerce, until 1932), whose meetings and proposals were always front-page news in the Courier, floated seamlessly and likely profitably between their businesses, law firms, service on town boards, and leadership of Rotary Club and other civic organizations. Some members of the Chamber’s leadership, including Wheeler, were stockholders in Berkshire Airways Inc. while also serving on various town boards and in other municipal roles. Their business interests intersected often with civic affairs; what today we would consider conflicts of interest worthy of recusal were common. The pages of the Courier and Eagle show the broad scope of their activities and influence.

The airport’s early ownership began with Wheeler’s powerhouse group of the town’s leading men [sic], and included a period when it was leased to Major Hugh Smiley, the wildly successful Egremont-based owner of local hotels like The Berkshire Inn, along with stores, restaurants, and the Jug End Barn ski resort.

Next up, in 1937, the airport was sold to Andrew L. Somers, a member of Congress from New York with a 40-room house on a 300-acre Monterey estate. He taught his many children to fly: His 12-year-old son made headlines in 1936 for soloing over Long Island Sound, and a syndicated Washington, D.C. columnist soon dubbed the Somers clan “the flyingest family in Congress.”

Then came James F. Tracy, a local garage owner, pilot, projectionist for 36 years at the Mahaiwe Theater, brother of the town’s longtime fire chief, and member and chairman of both the Selectboard (then called the Board of Selectmen) and Finance Committee. He purchased the airport in 1941 while he was the Selectboard’s chairman and soon launched substantial prewar and wartime improvements, including construction of a better runway.

Nothing’s been found in the town’s files or reflected in decades of news coverage of both aviation and town affairs that show Tracy or the others -- or Koladza, with one exception, after he took over in 1945 -- received approvals for buildings or expansion at the preexisting nonconforming property. (Among the town records reviewed for this series were all Zoning Board of Appeals files from 1937 to 1971.)

In those days, newspaper articles in early January routinely included a report of the building inspector’s work and the dollar value of permits issued the prior year – a contemporaneous recording of construction activity. The only reference to a permit for the airport in those articles in the Eagle after 1931 is a building permit for overnight T-hangars that Koladza planned to install in 1946; there was no sign of board approvals that would be necessary to secure such a permit.

The wartime period further established the airport as something not quite like other properties in town. No one disputes it was far busier during and immediately after the war than in 1932; the ZBA’s decision last year said as much. If the owner of the airport and recent chairman of the Selectboard -- the same person -- built a new runway to enable expanded operations, with newspapers reporting on several visits by federal and state aviation officials to view his progress, it’s hard to imagine anyone standing up to protest an improper “expansion of use” or complain about missing permits. Local boys were training at the airport to fight and die in a world war; a piece of paper labeled “zoning bylaw” certainly wasn’t going to get in the way. In that context, there was little incentive for Tracy to reveal the airfield’s problematic zoning status by going before town boards for proceedings that would be reported widely.

And then in February 1945, as the war in Europe neared its end, two F4U Corsair fighter-plane test pilots from Connecticut, Walt Koladza and Charles Sharp, took over the field and carried the thrill, glamour, and emotion of wartime aviation deep into a community filled with returning vets and their families. Koladza’s wasn’t an unfamiliar face: Prior to his work at Chance Vought, the Connecticut-based manufacturer of the Corsair, he had spent a couple of years training cadets from The Berkshire School and others at Tracy Field, as the Great Barrington Airport was formerly known.

Throughout the war, the pages of the Courier and Eagle were filled with tragic stories of those from Great Barrington who were killed, injured, and missing, alongside tales of those serving on active duty around the world. Many young aviators from the Berkshires lost their lives while flying missions in Europe and the Pacific. That included Housatonic’s 2nd Lt. Edward R. Budz, the first combat fatality for the town, killed in July 1942 while serving as navigator aboard an Army Air Corps B-17E Flying Fortress in the Pacific. His plane crashed moments after takeoff in a tropical storm as it headed from Queensland, Australia on a bombing mission to Lae, Papua New Guinea. That November, nearly 5,000 people attended a parade in Housatonic in his honor and for the dedication of a war memorial. (The Adams-Budz VFW Post is named in part after Budz.)

It’s hard to fathom who would challenge Koladza’s expanding aviation activities after he and his wife bought-out Sharp in 1946 and steadily grew Berkshire Aviation Enterprises in the postwar boom years. His airport was training those who returned home with GI Bill funds in hand, ready to learn to fly, and he soon offered charter flights that connected Great Barrington with the exciting new world of commercial aviation.

Locals who received their pilot’s license at Koladza’s airport made the newspaper; for many years the Eagle had a section called “Airport Activities.” Koladza had helped deliver the advanced fighter planes used to defeat the Nazis and Imperial Japan, and he trained local boys who might fly them. Was some Town Hall pencil-pusher or an airport neighbor waving the zoning bylaw going to stand in his way or ground his planes? For almost half a century, until 1990, none tried.

How the airport story unfolds from here will have a lasting impact not just on what level and kind of flight operations are permitted on the Egremont Plain, but also how the town approaches other issues that may seem far afield from airplanes. Because while an airport and the world of aviation are at its center, this is at least as much a story about what’s happened in Great Barrington over the last 100 years, right up through the airport hearings that begin in two weeks.

That includes last century’s hand-in-glove relationships between business interests and an underfunded municipal government led by a Selectboard of three men who, for perhaps longer than most would like to admit, were called and acted like “the town fathers.” It includes the extraordinary and lasting influence of the World War II years on the community’s view of the airport, embedded further when it was acquired by a wartime test pilot. And it’s also the surprisingly fascinating story of the history of zoning in Great Barrington -- a sentence that has almost certainly never before been written in the English language.

In the end, this is a story of how a community tries to solve a complicated and multifaceted problem. The airport and what it represents -- excitement, history, opportunity, and fond memories for some; noise, pollution, environmental risks, and years of rule-breaking to others -- is inseparable from current economic, demographic, and social currents in this evolving community. That’s clear in both the rhetoric and the illusory battle lines that some have drawn for their own ends: Longtime residents versus new arrivals, the wealthy and those less so, and perceptions of full-time residents and those with weekend and vacation homes.

The Selectboard can vote to wipe away questions and concerns about past and present activity at the airport if it decides, per the special-permit requirements, that the benefits from the airport outweigh any negative impacts. Its five members will have to look both backwards in time and forward into the future to make that judgement.

∎ ∎ ∎

NEXT: In part two, the airport’s early years.