Rick Solan first took to the skies when he was four or five years old. And, as he tells it, he never wanted to do anything else. His grammar-school teachers soon noticed: As in the old saw, Solan looked out the window and was mesmerized more by the clouds above than with the far less interesting reading and math lessons down on his desk.

“That was it,” he recalled of that maiden flight from what’s now a private airstrip in North Canaan, Conn. Back then, that airstrip was owned in part by his cousin, the legendary local aviator Stanley “The Flying Farmer” Segalla. “I said, ‘This is pretty cool,’” he told me during a conversation late last year. “I just loved looking down, flying low and slow.”

It was probably 1960. And he would soon visit the Great Barrington Airport (GBR), about a half-hour north of home. Not long after that first flight, Solan remembers that his father brought him to that field on Egremont Plain Road to see a new airplane hangar. “I looked up at this big hangar, and all this new tar and all the airplanes, and that was it,” he said.

It’s a hangar—and an airport—that he now owns as majority partner in Berkshire Aviation Enterprises (BAE) and its privately owned public-use airport in Great Barrington. It’s also among the buildings that an ongoing legal challenge in state Land Court says were built years ago without permission, for use in a business that expanded beyond what zoning allowed—things that happened, in large part, long before Rick Solan arrived on the scene.

By the summer of 1973, he was coming to Great Barrington from Canaan almost every day. It was a lot of driving and a lot of work: Back and forth between a midnight-to-8-a.m. job stocking shelves at the A&P supermarket near home, then working as a line boy moving and fueling aircraft and doing other chores at the direction of Walter J. Koladza, who at that point had owned the airport for nearly 30 years.

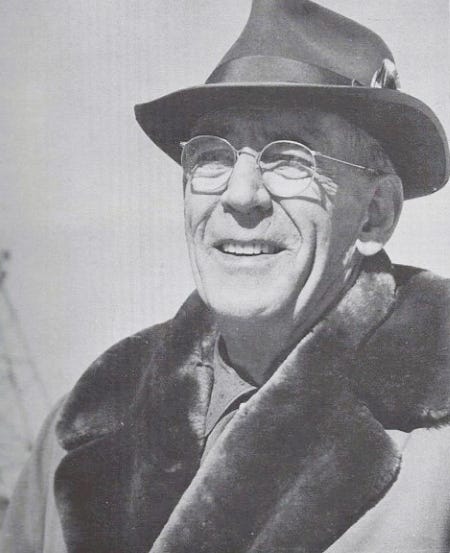

Koladza was notoriously frugal but also a committed teacher. He was happy to trade flight time and instruction for help around the place. So Koladza trained Solan through multiple certifications beyond his initial private-pilot’s license, providing much of that instruction in trade for help at the field. Solan still paid for a portion out-of-pocket.

Along with Koladza’s frugality came a work ethic: He rarely took vacations and was typically at GBR seven days a week. And he hated seeing someone with nothing to do. “If you’re sitting around idle, he’d say, ‘It’s time to get some rotor time,’” Solan recalled. But that didn’t mean taking to the air. “Rotor time was riding the lawn mower, because the blade cutters going around looked like a helicopter,” he told me, describing the acres of grass to be cut at the 90-acre property—some of which is in a state program that reduces taxes on land that’s used for agricultural purposes.

There was also “turbine time,” which meant heading out to the repair shop to run the vacuum cleaner while BAE’s longtime chief mechanic Rocco Traficante serviced the planes.

Koladza agreed to swap help from Solan, which later included some part-time flight instruction for BAE, for the vital training that set him on his career path. “I really couldn’t afford to fly, and Walt basically gave me all this. I was his indentured servant for years,” he said. “If it wasn’t for him …”

Solan soon headed off to a small aviation school near Boston and earned an associate degree and a second in air-traffic control. He returned to be an instructor at GBR for a couple of years. Then, during the winter of 1976, he left to teach other pilots to fly multi-engine aircraft at Hanscom Field in Bedford, Mass.

Not long after, he was hired on at regional carrier Bar Harbor Airlines in Maine. That’s where he spent seven years flying the Beechcraft 99—a twin-engine, 15-passenger turboprop commuter plane—logging the hours and acquiring the experience needed to move to a major airline, bigger planes, and a solid career. But the majors weren’t hiring much in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He was also in the queue behind military pilots back from Vietnam who were given priority. “And rightly so,” Solan told me.

He still returned to GBR from time to time. He wasn’t yet married: Solan met his future wife, Dena, when they were children. While he was up in Maine, she wasn’t ready to get married. And he was working constantly, taking on extra work at Bar Harbor to continue racking up the time in the air he needed to advance.

In 1984, the door finally opened. A two-tier pay scale implemented in a new union contract at American Airlines meant the airline went “hog wild” with new hires, Solan said. Timing was everything, as it often is in the airline industry. When he signed on, American had 4,500 pilots. Today it has nearly four times that number. “When I left, my seniority number was 95 out of 16,000,” he said. (Solan retired in April 2020.)

After just four years with American, he was promoted to captain and was helming the DC-10, a three-engine widebody made by McDonnell Douglas. Ultimately, he spent more than 22 years flying the enormous Boeing 777 for American around the globe. “Paris, Tokyo, Santa Domingo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo, Brazil, Germany,” Solan said, rattling off destinations. Of his first time flying a large passenger jet, he said, “It took a month to take the smile off my face. It was just like, ‘I get paid for this?’”

Eventually, he became a check airman, or training captain, who flew alongside new 777 captains who required 25 hours of supervision for certification; first officers needed him looking over their shoulder for 15. “It was a passion of mine. I just love teaching,” he said, suggesting that not all pilots like instructing others—or even like to fly as much as he does. “That’s why most airline guys that are retired, today they’d be on a golf course sipping a Mai Tai by the pool.” But Solan still spends many hours a day buckled into one of Berkshire Aviation Enterprises’ training planes, teaching those who want to fly for the fun of it or because their eyes are stuck on the clouds, like his were—and dreaming of a career like his.

As a successful commercial pilot, he had fulfilled his dream. It was also one his parents had for him; they “scrimped and saved” to help him on his path, he said. His father, Joseph R. Solan, was badly injured while an Air Force mechanic in the early 1950s and transitioned to a career with Connecticut’s Department of Transportation. Because of his injuries, he couldn’t get a pilot’s license, but Solan told me that his father still loved to fly. While Solan was growing up, they shared time together building and flying remote-control airplanes. And when he was with American, he took his parents on trips to Germany, Switzerland, and sometimes on quick weekend jaunts to Bermuda.

Over his many years at American, and even during the last few years of his time at Bar Harbor Airlines, he still spent time helping Koladza at GBR. Solan’s wife worked as a referee and umpire for baseball, basketball, and soccer matches, so she’d often be at games while Solan brought his son, Joe, up to the airport.

When I asked him what’s changed most since he first started flying, he said aircraft navigation via GPS. “When I was growing up, we didn’t have GPS, so we had a paper chart. And if we got lost, we had to figure out where we were,” he said. Indeed, stories of planes landing at the wrong airport because of navigation errors are a distant memory. Though when he told me that other advances allow some modern jetliners to land themselves with no pilot intervention, that seemed almost as significant; I stored that tidbit away in memory for use as a tranquilizer when next crammed into economy during heavy turbulence.

When I ask him about being a check airman—a pilot’s pilot, assigned to certify the pilots to whom we surrender our lives for some number of hours in a thin metal tube—he tells story after story, shares anecdotes recent and ancient, describes people he knows well. And he does it all without seeming to stop for a breath. Whether explaining how a mid-December nor’easter is taking shape south of his airport, or how modern jet aircraft land themselves, or describing the time when his son Joe, as a toddler, cracked up the notoriously cranky and curmudgeonly Koladza with some literal potty humor, the words fly at supersonic speed.

These days, Solan is at the airport nearly every day, working alongside his similarly passionate son, a 24-year-old certified flight instructor who is the airport manager. “My story basically starts with his story,” Joe Solan told me during our first conversation last summer. He described growing up around the airport, learning to fly, and soloing at 16. The younger Solan is more guarded than his father, at least around a reporter asking questions. But over a few months observing him from a distance as he talked to students and pilots, and juggled his many tasks at GBR—some as mundane as moving airplanes in and out of hangars and pumping fuel for visitors—it’s easy to see the father in the son. He’s a young man in his element, with the same focus and passion.

He told me that his father is pretty old-school when it comes to flight training: Students still learn how to navigate with charts even though they can rely on technology in the air. He called him “an airline legend,” describing trips to an American Airlines operations center where people showered praise on his dad, a respected veteran pilot who spent decades teaching others to master the largest airplane in American’s fleet. On a different scale, Rick Solan still does now what he did then, but in small planes and for the next generation of pilots.

Joe Solan shied away from talking about the recent challenges his father has faced—and not just from the Sturm und Drang of neighbors’ complaints about the airport; long nights in front of town boards; and, along with BAE co-owner Jim Jacobs, writing a steady stream of presumably large checks to lawyers. Trying to keep the airport going is Rick Solan’s all-consuming project, and it hasn’t been easy.

Meanwhile, since 2016, Solan has lost most of his immediate family: His wife, Joe’s mother, died in 2019, not long before BAE’s second failed attempt to secure the special permit that would lift zoning restrictions on the airport he inherited with three others in 2008, and that BAE is again seeking this month. His father, Joseph R. Solan, had passed a year earlier at 89. A couple of months before the first and perhaps most contentious public battle with neighbors and the town in 2017, his brother, who had earlier suffered a stroke and was cared for by Solan and his wife, also died. And his mother, Teresa P. Solan, passed away in March 2021.

2017: The first signs of trouble

It was those 2017 hearings in front of the Selectboard that first introduced many people to its owners and issues surrounding the airport, which was formally established in 1931. Along with then-airport manager and former United Airlines pilot Ken Krentsa, who lives in Stockbridge, and Lenox real-estate and land-use attorney Lori Robbins, Solan tried unsuccessfully to address a steady stream of complaints and accusations and make the case that the airport could be trusted to be a good neighbor if unshackled from residential zoning restrictions and allowed to build hangars to garage some more planes out of the elements.

Video from those 2017 hearings show a heated battle in front of a Selectboard at times blindsided by the complexity of the issues, the intensity of feeling, and dramatic gaps in both available information and the expertise needed to evaluate what they were told. That was evident with respect to zoning, aviation issues in general, and the type and level of airport operations more specifically. Selectboard member Ed Abrahams, who quizzed the airport’s representatives on a host of issues, returned repeatedly to the past, suggesting that the current ownership didn’t preserve “a delicate balance that Walter Koladza was able to maintain for a lot of years.”

The hearings were rife with inaccuracies, misstatements small and large, and misunderstanding on all sides and from all corners. Residents waved printouts of random FAA regulations they said applied to the airport (most didn’t). Krentsa, a man with a deep voice and engaging reasonableness, calmly tried to fill in gaps and address misconceptions and concerns, only to be called “a clown” by one irate abutter. Selectboard members often seemed uncertain and overwhelmed.

It was tense. “My name is Rick Solan, I’m the bad guy, I’m the guy that owns the airport,” Solan said with a noticeably sharp edge when he took to the microphone on February 27, 2017, to respond to the onslaught.

Solan recently confirmed what Krentsa also told me: The hearings blindsided them. “We didn’t think that [the hangars and special permit] would be the thorn in the lion’s paw,” he said. “We didn’t expect that, for some reason. Because, you know, we figured we never had much trouble with any of the neighbors.” He said there were phone calls with complaints on busy days, and, of course, a years-long and very contentious battle with Claudia Shapiro, whose property abuts the west end of the airport. But regardless of whether it was an actual lack of awareness of long-simmering issues, or a failure to adequately address them, the die was cast.

The 2017 hearings stretched from February into July. Robbins, a longtime real-estate attorney with broad experience and expertise, may have erred by presenting the application as if it would be uncontested and a fait accompli—adopting a tone that was, in the end, a bit off-key for the setting. And in the face of what unfolded, she didn’t seem to adjust along the way: Perhaps too self-assured, repeatedly dismissive of neighbors’ complaints, overly confident in the legal arguments, and perhaps not deferential enough to the board members from whom she needed to corral four ‘yes’ votes. (Robbins and I exchanged emails last month to arrange an interview, but she didn’t respond to my last scheduling inquiry.)

(Disclosure: Robbins represented the seller when I purchased a house in 2016.)

It’s likely that Robbins—like Solan and Krentsa—didn’t expect so much pushback. Each hearing brought new unconfirmed information, additional unanswered questions, and even more confusion. At one hearing, airport neighbor Jim Weber, a percussionist with Berkshire Bateria, blew his band-leader’s whistle long and loud to demonstrate what he said was the volume of noise from planes flying over his house, which is under the flight path on Pumpkin Hollow Road, a block from the airport. He’s lived there with his wife Teri since 1998.

By the fourth hearing, in May 2017, airport co-owner Jim Jacobs had had enough. With skepticism from the board and complaints from neighbors coalescing into a wall of opposition, Jacobs was caught on CTSB-TV’s microphone whispering to Robbins, “We need to pull this.” She replied, “No, not yet,” but Jacobs was insistent. “We need to pull this,” he repeated. “We need to pull this. Seriously, we need to pull it. You’re paddling upstream,” Jacobs told her.

He then stunned the board and a packed hearing-room crowd by announcing, “I don’t want a special permit. I’m not interested in it.” Board Chair Sean Stanton, after a beat, asked, “So then why are we here?”

Jacobs offered a version of the airport’s history and its operations, insisting at length that “we’re good guys.” He added that during and as a result of the hearings, the airport was “being harassed”—a claim that elicited loud groans from airport critics. Soon after, BAE withdrew its application. Former Berkshire Edge Managing Editor Terry Cowgill described that night as “a public hearing like no other that this writer has covered during 20 years as a journalist.”

These days, when talking about these issues, Solan seems to have softened some from the edgy impatience on display a few times during those 2017 hearings, though he admits he gets frustrated and can have a short fuse. He told me that he hands off contentious phone calls to his son—though based on interviews with airport neighbors, it’s clear that raised voices have at times been heard on both ends of the line.

Since then, the Solans have carried on, benefiting from a flight school that has grown far busier since 2017, and which has been the focus of complaints since 2020, culminating in what’s now pending in Land Court. (BAE also failed to get a special permit in 2020; it was turned down in a unanimous Selectboard vote.) Clearly protective of his father, Joe Solan’s bond with him is clear. “My dad is the hardest-working person I know,” he told me recently. He said he knows that sounds like a cliché but insists it’s true. “And he’s my rock,” he said, alluding, it seemed to me, to recent challenges both personal and professional for the Solan family.

When I asked Rick Solan to describe the hardest part of his work at the airport, he said there isn’t one. “This is the love of my life,” he said. “I mean, we have a lot of regulations. We have to keep up with FAA regulations and certifications, we have OSHA laws. Just like any other business you have a bunch of laws, you got to keep up. But for me, it’s a labor of love.”

Nearly every time we’ve crossed paths since last June, Solan has said at least two things: First, that the airport is busy, especially the flight school. And second, that he’s committed to doing everything he can so it will still be there for the next Rick Solan who dreams of learning to fly. Even with the challenges, he likes what he has. “We’re just a small country airport that makes money from tie downs, maintenance, and flight instruction,” Solan said. “Where else can you just have grass and no fences? It’s a throwback in time.”

Early aviation and GBR’s origins

The origins of the airport he loves and the problems it faces today both flow from what happened during that throwback period: primarily from 1929 to 1932, when the airport was established and zoning was implemented, and then also during a period of growth from the early 1940s and into the 1960s, at least.

It’s hard to overstate the fascination with airplanes and aviation in the early decades of the last century, starting with the Wright Flyer and its 12-second voyage at Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903. While his brother, Wilbur, ran alongside in the sand, Orville Wright reached the non-nosebleed altitude of 10 feet and covered a distance about one-third the length of a football field.

That inaugural powered flight came roughly 400 years after Leonardo da Vinci sketched his proposed bird-like flying machine. And it was 120 years after a sheep, rooster, and duck made the first journey of living things into the sky aboard a hot-air balloon in France. They rose to 1,500 feet and drifted about two miles before landing safely. (What the three discussed while airborne remains lost to history.)

Pilots and planes made frequent appearances across the Berkshires over the next couple of decades. Balloon flights, successful and failed, were attempted here as early as 1882, according to historian Bernard Drew’s encyclopedic and indispensable “Great Barrington: Great Town, Great History.” Long before it was an airport, the field on the Egremont Plain hosted Curtiss biplanes and early barnstormers who sometimes flew into and over the town, landing on that grass field in all directions.

Charles S. Witmer, a member of the Curtiss Aeroplane Exhibition Team traveling the country to spark interest in aviation, landed the first plane in Pittsfield on July 4, 1911 in front of a crowd numbering in the tens of thousands. As he departed amidst heavy winds and a thunder-and-lightning storm, he crashed shortly after takeoff and suffered “a badly injured leg,” according to news coverage and a biography of Witmer.

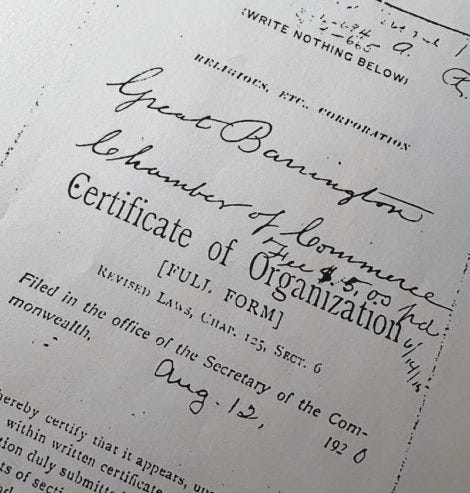

In Great Barrington, interest in aviation and the possibility of an airport was advanced—as were so many other projects, policies, and enterprises—by the Great Barrington Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber was formed in 1920 by a group led by Robert K. Wheeler, born in 1892 into the family that, in 1871, started what became the Wheeler & Taylor insurance agency, and who served as the Chamber’s first president. The organization of local business leaders aimed to “[foster] the spirit of Great Barrington, the commercial welfare of Great Barrington, [to] increase[e] trade … and to assist in any other matters pertaining to the welfare of Southern Berkshire,” according to its 1920 charter.

It embraced its charge to “assist in any other matters” wholeheartedly and with vigor. The Chamber operated almost as a branch of government, forming various committees and study groups and taking action on municipal issues of its own accord. Its activities filled the pages of the Eagle and Courier, with the latter filling its front-page coverage with as much detail as meetings of the Selectmen and other boards. Its members traveled the state investigating how other communities were addressing problems from water systems to street lighting, and it held countless meetings and events meant to boost the Berkshires’ tourist economy. (As discussed later in this series, it was a Chamber subcommittee that advanced the idea of zoning and then rallied support for it.)

Wheeler was a popular young man in a hurry. At Searles High School, he was elected captain of the track team in 1911 and president of the athletic association a year later. After his World War I military service, he was named the first commander of the new American Legion post in Great Barrington in 1919. A year later, after being nominated by both Democratic and Republican caucuses, and while president of the new Chamber, he won election at age 26 to the Selectboard. He was immediately named as the youngest chairman in history. “The young men are strong for him,” wrote the Berkshire Courier in its election preview.

Still, he was defeated in his second bid for re-election in March 1922, and lost a bid for School Committee in 1925 by one vote. But he later served in other town roles, frequently as moderator at town meetings and as a member of the Finance Committee from 1932 to 1936. Wheeler was active in countless projects and ventures: When he died in 1980, an obituary overflowing with details of his business and civic involvement called him “a leading force in many of the activities and institutions that have shaped the character of Berkshire County.” The Eagle’s effusive memorial editorial was titled, “Robert K. Wheeler, a force for good.”

Drew’s history of Great Barrington discusses Wheeler at least thirty-two times across its 600-plus pages, far more often than any other person. (A little-known local writer, a certain “W.E.B. Du Bois,” was second with 20 mentions.) In his introduction, Drew credits Wheeler as among just a handful throughout the town’s history “who behind-the-scenes made sure businesses kept going, that properties found new owners, that the local economy thrived.”

Drew told me last month that Wheeler was “one of the more energetic businessmen of his generation,” involved in a host of business, municipal, and philanthropic ventures. He owned or invested not only in the airport and his own insurance and real-estate business, but also in Mountain Sand & Gravel, Jug End Barn, Whalen & Kastner Garage, the Red Lion Inn, Henry J. Cairns’ G-Bar-S Ranch, and the Barrington Industrial Corp. His civic involvement was significant and “as far-ranging as the Mount Everett Reservation Commission and Fresh Air Fund, Gould Farm and Fairview Hospital and Berkshire Music Festival,” Drew said. And his philanthropic efforts were noteworthy. “While there surely was often a profit involved, at times there were examples of simple generosity and caring about his community,” he summarized in an email.

In the 1920s, aviation-related activities were happening at least informally at the Rossi Farm on Egremont Plain Road. In June 1928, the Eagle reported that 26-year-old Edward Lyman of Pittsfield had leased a portion of the land with plans to “spend the summer there in commercial flying with his Standard plane,” ferrying passengers. It had been used previously by the Gates Flying Circus and others; the Eagle described it as “a large level tract of land [that] is readily adaptable for airplanes.” Lyman didn’t get far, though: In early August he sold the plane after discovering that he didn’t have the 200 hours of flight time legally required to carry passengers.

Flight was different back then: Accidents were common, which gave aviation more of a daredevil thrill for those on board and others watching from the safety of the ground. Navigation was by magnetic compass, so planes flew much closer to the ground, often only a few hundred feet up, so pilots could use roads and landmarks to guide their way. In the mid-1920s, the federal Air Mail Act helped jump-start a commercial-aviation industry that began to include not just mail and cargo but also passenger service. And later, it was FDR’s 1938 Civil Aeronautics Act that began to systematize and regulate air travel.

An airport takes shape

The Chamber had been discussing since at least the fall of 1928 what steps it might take to advance aviation in Great Barrington, with Wheeler speaking about it to a board of directors meeting that September. An aviation committee was formed with Wheeler as chairman. It’s unclear if he had an interest in flying beyond the role an airport might play in the local community. Regardless, it was his committee that quickly moved things along at the nascent airport. In just a few months, he secured an option to buy the Rossi property after it was examined and “approved by an expert aviation engineer.”

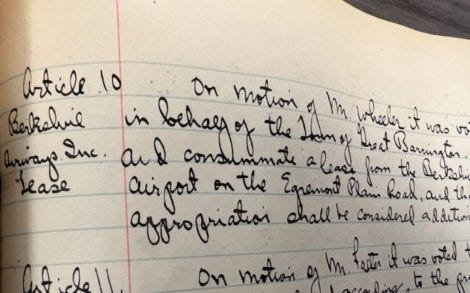

By April 1929, things were advancing. The Chamber issued a prospectus as it sought investors for the new Berkshire Airways Inc., with a corporate board headed by Wheeler and filled with other Chamber members. Subscribers’ investment would fund the purchase of about 100 acres for $7,500 and the cost of developing the field, estimated at an additional $2,500.

“Following the trend of civic development, the Great Barrington Chamber of Commerce, through a committee, has investigated the need and advisability of an airport in Great Barrington,” it announced. “With the subject of aviation before the public in print practically every day … there is little need for further discussion of this point,” it added definitively. “Within a comparatively short time,” the brochure promised, “an airport will be as essential to Great Barrington as the railroad station or garage.”

It sought investors at $25 per share, or $435 in today’s dollars. That valued the enterprise at close to half a million in today’s dollars. (A 2011 MassDOT study estimated the “replacement cost” of the airport—that is, to establish an entirely new airport in Great Barrington, if even possible—would cost nearly $18 million.) “It is not recommended as an investment for early financial return, though such a possibility does exist,” the prospectus suggested.

The brochure described plans to lease the field “to one of the largest airway companies in the East” which would offer regular flights between New York, Albany, and Springfield, or to a different company that would establish a flight school. “There is a possibility of profit from the regular use of the field for occasional flying,” it promised, something that might amuse today’s small-airport operators. “If you want to make a million dollars in aviation,” the old saying goes, “start with five million.”

The brochure also teased that the property included “a gas and oil privilege and one oil company is already interested.” It’s unclear if that refers to rights to—likely without success—drill for oil and gas on the property, or if it suggests fuel storage or a gas station. There were many of the latter proliferating across the Berkshires to serve the rapid growth in automobile usage.

As plans for Great Barrington’s new airport moved ahead, aviation continued to fascinate. The Eagle issued a special “Airplane Edition” that was delivered via airplane to Canaan, Conn. “at 100 miles an hour” as part of a marketing campaign. And that year the Eagle ran a regular column called “Ground Flyin’” that featured news of local pilots’ achievements, planes purchased, and tidbits about aviation.

In January 1930, the Chamber’s annual report boasted of its success toward establishing an airport. And by the summer, Berkshire Airways Inc. continued checking off boxes: It had purchased the field, financed in part with a mortgage held by the former owner, Jacob Rossi. And it announced plans for an air circus “in which several planes will take part” as it sought to raise another $5,000 to build a hangar. (A hangar was required to be considered an “airport” and not just a “landing field.”)

A year later, the company, with Wheeler as president, hired Priggen Steel Builders to construct that first hangar, “which will add greatly to the attractiveness of the airport,” wrote the Eagle. (That hangar still exists, moved in 1960 to the north side of the airport near the Green River. From the air, pilots can see “GT. BARRINGTON” on its roof.) The company teased a possible September 1931 dedication and said it might become a stop on an air-mail route from New York to Burlington, Vt.

By now, the Chamber’s aviation committee included Wheeler, local oilman John B. Hull, Mahaiwe Bank President Joseph H. Lansing, Joseph H. Maloney of the Main Street furniture store and later Birches-Roy Funeral Home, and Frederick H. Turner, who was about to begin 35 years as president of Great Barrington Savings Bank. Many were also stockholders and board members of Berkshire Airways. Indeed, the Chamber and Berkshire Airways were almost indistinguishable. And both were deeply intertwined with town government in a knot that could easily be described as Gordian. For example, the airport’s board included Frank J. Brothers, president of the Chamber in 1930, almost certainly a Berkshire Airways stockholder, and, not insignificantly, also Great Barrington’s town counsel from 1927 to 1934.

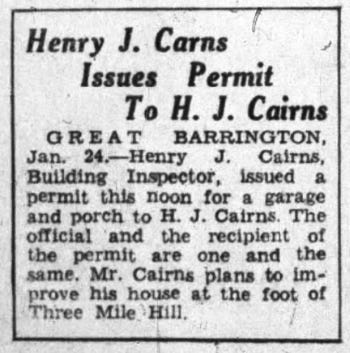

And then there was airport board member and local businessman Henry J. Cairns, whose interests included lumber and fuel-oil businesses and who would later own a ski resort and dude ranch where Butternut Basin is today. He became Chamber president in 1931 while also president of the Rotary Club. The same year, Cairns was elected to the new Planning Board and served as clerk as it drafted the town’s permanent zoning bylaw that would go into effect in 1932. (News accounts later referred to him as Great Barrington’s “father of zoning.”) Surprisingly, even with a Berkshire Airways board member drafting the new zoning bylaw, the airport property was still zoned residential, establishing its preexisting nonconforming status in 1932.

Highlighting the complexity of these connections, and that era’s substantially different view of small-town conflicts-of-interest, when the new zoning bylaw took effect in September 1932, Cairns was immediately named by the Selectmen as the town’s first building inspector. And four months later, in a red-letter day for Eagle headline writers, news broke that “Henry J. Cairns Issues Permit to H.J. Cairns”—he was building a new garage and porch at his house and saw no problem issuing the required paperwork to himself. “The official and the recipient of the permit are one and the same,” the report noted wryly.

That deep connection between the Chamber, town officials, and Berkshire Airways was clear from the start, and helped set down the roots of the airport’s special treatment in the years to come. In February 1930, the Chamber and Berkshire Airways even held their board meetings together at the Great Barrington Coffee Shop. Once the Chamber’s business was done, “… Robert K. Wheeler presided at the meeting of the Berkshire Airways Incorporated which followed the [Chamber] directors’ meeting,” the Eagle reported.

Meanwhile, interest in aviation continued to grow. An air show in Pittsfield included planes flying over the city and dropping small parachutes with vouchers for a free plane ride. And a September 1930 weekend event at the nascent Great Barrington field promised that “the usual short rides and safety first stunting will be included.” Pittsfield’s American Legion post sponsored a weekend air show in August 1931 that featured, according to the schedule, an “aerial parade over the city, 12 or more planes participating,” along with a dead-stick landing competition, fireworks, drum corps, and exhibition flying.

A dedication in front of thousands

A strong military association with early aviation was common; in the wake of World War I, the armed services were expanding their air forces. So it was not a surprise that the dedication of Great Barrington’s airport the following month was also organized by the local branch of the American Legion. Airplanes from the Massachusetts Air National Guard flew out from Boston for the dedication—in aircraft likely somewhat less disruptive than the Blackhawk helicopters that today can rattle windows near the airport. And planning for the event was overseen by William J. Connelly, the county’s Commander of Legion. Wheeler prepared a souvenir booklet distributed for the dedication; he was a member of the southern Berkshire post and had been its first president in 1920.

“About 20 planes will be zooming” over the area during the dedication of Great Barrington’s new airport, news accounts promised. And advertisements promised “3 Big Days” of “acrobatic flying, dead-stick landing, bomb dropping and balloon bursting.” Tickets were $0.25 per person, or about $5.00 today.

By the time of the dedication, the field had been leased to Great Barrington’s John and Louis Modolo and their Berkshire Flying Service. They were among featured pilots that weekend, as was Gus Graf, an early acrobatic pilot and parachutist, and the local Parrish brothers, Robert and Clarence. (A dedication-weekend fender-bender between planes owned by the Modolos and the Parrish boys led to a lawsuit. A few weeks later, the Eagle reported that the Modolos’ plane “has been equipped with new wings.”)

In advance of the airport dedication, the papers cheered the project: “The Egremont field is a natural airport and is sufficiently large to accommodate a large fleet of planes,” wrote the Eagle. “Its approaches are excellent and its all-around facilities are the best that can be found anywhere in the county.” Noting under a sub-headline that “Business Men Support Project,” the story highlighted both the new hangar and the airport’s powerful leadership: “Under the management of Berkshire Airways … which includes among its stockholders prominent business men of the town, a definite program of development has been launched.”

A Courier editorial chimed in to encourage attendance and hint at the future: “In years to come, the presence of an airport in Great Barrington may be of inestimable value to the Southern Berkshire section,” the editors wrote. “In order that the exercises of the week-end [sic] and holiday may be successful all citizens are asked to participate.”

Thousands attended what had “all appearances of a country fair.” Events included an air race each day to Mt. Everett and back. And the weekend featured a demonstration of an autogiro—an early helicopter. That same helicopter also made an appearance, of sorts, in Great Barrington last April. That’s when Zoning Board of Appeals member Michael Wise suggested that single autogiro demonstration, in pre-zoning 1931, was sufficient to establish that the airport’s preexisting nonconforming status should not limit helicopters there. His focus on helicopters didn’t go unnoticed: Wise was president of the Great Barrington Rotary Club in 2017 when it appealed a Selectboard decision to prohibit helicopters at the club’s popular Bike-N-Fly fundraising event. Wise told the board that helicopter rides were a significant attraction for what was, pre-COVID, the group’s largest annual fundraiser. Despite neighbor complaints, the board relented and helicopters were allowed.

The dedication-weekend festivities merited a mention in the Boston Globe, with a blurb on page 10: “3,000 See Planes Stunt Over Great Barrington,” it reported, describing 25 planes—though there were likely only about 12—and “unusual thrills.” The Eagle’s wrap-up coverage estimated 6,500 visitors over three days, grossing $1,625 for the airport’s coffers. The story said a highlight was when three national guard planes arrived “suddenly from the east [when] the roar of motors was heard.”

All of the work involved must have been exhausting: The Eagle reported that a few days after the dedication, Wheeler left town for a 10-day Canadian fishing trip.

A clever plan for new investment

What happened over the next decade at the airport was likely fairly modest. By 1934, the airport was being managed by Graf, who would run the airport until the early 1940s. The six-plane hangar was said to house an average of five planes by mid-1934. They were variously owned by Hugh Smiley Jr., son of the Egremont business tycoon, along with the Parrish brothers and others.

The Selectboard approved more fuel storage at the airport in June 1933, without any discussion of any expansion in use that might foretell.

Other news continued to bubble up from the airport. In 1935, Graf confirmed that inspectors from the U.S. Army had visited the airport and were considering establishing an army base there. Army officials were reportedly interested in where ammunition and bombs could be stored and if nearby accommodations were available for soldiers.

Despite the continuing fascination with aviation, and some activity at the new airport, it was becoming clear that any promised profit from the Great Barrington operation was likely far off. Improvements were needed, and in those early Depression years, investment was not easy to secure. But with FDR’s election and the rollout of federal relief programs, alternate funding sources were becoming available.

Among the initiatives under the president’s First Hundred Days program was the Federal Emergency Relief Act, which sent funds to states to quickly distribute to local governments. It began to be replaced by the Works Progress Administration in 1935, but funds still flowed under the program for another couple of years.

With the town deciding how to allocate its share of ERA funds, Wheeler’s Berkshire Airways proposed in 1934 that the town “take over” the airport, which would permit federal funds to be used to make improvements at the airport and provide jobs for unemployed local workers. The town would pay $1.00 to be in charge for five years via a leasing agreement, after which it would revert back to Berkshire Airways. The proposal seemed an easy win for the community during hard times—and for the stockholders of Berkshire Airways.

At a Berkshire Aviation stockholders meeting held that August, a committee was formed with a familiar name at the helm. Henry J. Cairns—the town’s first building inspector, owner of several local companies, former member of the Planning Board, current member of the Finance Committee, possessor of a relatively new garage and porch, and board member of Berkshire Airways Inc.—was tasked with lobbying the Selectmen to hold a special-town meeting as soon as possible. Their plan would make the airport eligible to use ERA funds to, initially, hire local workers and “remove stumps and regrade the field,” a benefit for the company, the airport, and the town.

Besides Wheeler as president, the officers of the company in the mid-1930s remained a who’s who of Great Barrington and south-county elite. They included Egremont’s Major Hugh Smiley, who was by then leasing the airport for his son; Town Counsel Frank J. Brothers, who was at that point also an associate justice of the Southern Berkshire District Court; Great Barrington Savings Bank President Frederick H. Turner; the multi-hat-wearing Cairns; and Selectman Paul W. Foster.

Reports presented to a Chamber meeting that month boasted that “the airport is at present doing more business than at any time since it was started about five years ago,” though whether that was well-timed marketing hype to appeal to town-meeting voters or based in fact is hard to determine. Indeed, nearly every time airport manager Gus Graf was quoted in the newspaper in the 1930s, he said the airport was “busier than ever.”

Things moved more slowly than the committee and stockholders hoped. No action was taken by the town for the rest of the year. And then, in January 1935, Wheeler made a surprise last-minute bid for Selectboard, entering the race just a few hours before his Republican caucus chose candidates for a February 4 general election. He lost.

It’s unclear why he sought the office but not inconceivable that it was to help advance the airport’s interests during a difficult period. The airport question would soon be in front of town meeting but only if it made warrant. Selectman Paul W. Foster was a board member of Berkshire Airways but wasn’t running for re-election, and at least one board member, Paul C. White, was likely opposed to the idea.

At that February 1935 annual town meeting, Wheeler, who was on the town Finance Committee, made the motion himself to authorize the Selectboard to lease the airport from his company, Berkshire Airways. With the town in charge, he no doubt explained to voters, ERA funds would pay local workers to improve the still-privately-owned airport. The town could then sub-lease the field to an operator.

Voters were described in news coverage as “air-minded” as they approved the motion, though not before longtime Selectboard member Paul C. White—the staunch defender of Housatonic’s interests who would in a few years clash repeatedly with Selectman and soon-to-be-airport owner James F. Tracy—spoke out in opposition. He said he favored using ERA funds for “projects that would be more beneficial to the town” like addressing “open sewers near the Housatonic School.” Wheeler defended the move and said those who invested money to develop the airport did it “as a civic enterprise.” The motion passed 124-15.

That overwhelming support wasn’t enough. After six months of effort, Cairns largely gave up trying to get the board to pull the trigger. He dispatched now-former Selectman Paul W. Foster to present the board with a lease that met ERA requirements but watched as $7,000 in federal funds were spent elsewhere. He pestered the board at meetings all summer and even sent a letter with a drop-dead August 7 deadline for action, noting the issue had been “hanging fire” for months. He pointed out that 20 other communities in the Commonwealth had already done the same thing to support their local airfields. But the Selectmen were uninterested or focused on other matters.

Still, Wheeler continued to try to bring the board around. The voters’ authorization had no deadline, and the Chamber’s aviation committee—still largely indistinct from the stockholders and directors of Berkshire Airways—voted to give the town five years to act. In early October, Wheeler invited the Selectmen to the airport to meet the visiting Ruth Nichols, a storied aviator who was passing through in a Curtiss Condor owned by Egremont’s similarly famous aviator, Col. Clarence Chamberlain. The Condor, an army bomber converted for passenger use, was one of the larger airplanes of the day.

Wheeler’s invitation also offered the Selectmen an opportunity “to enjoy a plane ride,” according to the Eagle. Several hundred came to see Nichols and go up in her plane; at least one flight was filled with “officials of the South Berkshire Chamber of Commerce and guests,” though it’s unknown whether any Selectboard members took flight.

Two weeks later, Cairns reported at a Chamber meeting that the so-called town fathers had still taken no action on the authority granted them in February. In the end, the town never took control of the airport and no federal funds were spent to improve it. If the Chamber-and-private-airport-corporation project was indeed solely “a civic enterprise,” as Wheeler told voters earlier that year, and not something from which the “leading business men of the town” hoped to profit, at minimum their patience had flagged. A little more than two years later, the airport was sold.

Congressman Somers takes over

The new owner was a different kind of mover and shaker: Congressman Andrew L. Somers, a wealthy Brooklynite whose family owned an enormous summer estate in Monterey. It encompassed 300 acres near Lake Garfield and included a 40-room mansion and 24-room rustic lodge on the lake, both built by his father, who had prospered as an importer and director of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Known as “the flying Congressman,” Somers was a pilot and represented a district in Brooklyn.

He purchased the airport in November 1937 for $2,000 (about $40,000 today) and assumed the mortgage still held by Jacob Rossi, who had issued the mortgage to Wheeler’s group in 1929. There were four planes at the field in 1937, according to news reports, and Graf continued to manage the airport for the new owner. By 1939, the airport had seven based planes; a news story that July said “there are 15 to 20 students, some of whom have made their solo flights this season.”

First elected to Congress in 1924, Somers held the job until his death in 1949. He served in France as a naval aviator during the last year of World War I; his son Arthur was also a Navy pilot. And five months before purchasing the Great Barrington Airport, his 12-year-old son Edward landed on front pages nationwide after he made a 15-minute solo flight at Floyd Bennett Field, New York City’s first municipal airport. He wasn’t yet 16 and therefore earned a sanction from the Department of Commerce, then the national aviation regulator. A syndicated Washington columnist soon dubbed the Somers clan “the flyingest family in Congress.”

Somers, who helped shepherd key elements of Roosevelt’s first-year agenda through Congress in 1933, spent summers with extended family at their Monterey compound. He was a staunch defender of his Jewish constituents: When Leni Riefenstahl, the German actress and filmmaker-propagandist came to the United States in 1938, Somers demanded she be deported. “The only fruit which could result from allowing this Nazi propagandist to pursue her aim would be implant in our beloved and free land the seeds of racial hatred, religious intolerance and mutual distrust which at present are rampant in central Europe,” he said in a telegram to Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins. (She wasn’t deported.)

Somers would later earn a certain distrust of his own among feminists and students of women’s contributions to the war effort. When a wartime proposal to create the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) reached the House floor in 1941, Somers was incensed. “I take this opportunity to express my definite and sincere opposition to what I consider the silliest piece of legislation that has ever come before my notice in the years I have served here,” he began during a floor speech, rallying to his sexist cause. “A woman’s army to defend the United States of America. Think of the humiliation. What has become of the manhood of America, that we have to call on our women to do what has ever been the duty of men? The thing is so revolting to me, to my sense of Americanism, to my sense of decency that I just cannot discuss it in a vein that I think legislation should be discussed on the floor of this House.” (His speech is noted frequently in scholarly papers about women’s progress during World War II.)

There’s little evidence Somers was much involved at the airport during the late 1930s or made any investment. Manager Gus Graf continued to run the place; he would later head south to that airfield in Canaan where Rick Solan would get his start about 40 years later. And it’s not clear how the airport was doing financially, but it’s safe to assume the answer was not well, if even “the leading business men of the town” couldn’t make a go of it.

Somers either lost interest, saw the property as a money-loser, or both. Because in 1941, after Jacob Rossi died, his wife Jennie Rossi was granted permission by a judge in Berkshire Superior Court to foreclose on Somers’ outstanding $4,500 mortgage, which she did. Somers didn’t bother to appear for a court hearing on the matter.

The Selectboard chairman buys the airport

And that’s when Selectboard Chairman James F. Tracy, an avid pilot who had once owned his own plane, purchased the airport as part of that foreclosure sale. He may have expected that, with war clouds well past the horizon, it would soon become more valuable. And he certainly had high hopes for commercial aviation after the war, which would mean a busy, profitable airport or a lucrative sale to the town. Indeed, state and federal officials were already actively encouraging municipalities to acquire land for airports and make other plans for what they promised was a coming aviation boom.

Tracy, born in 1896, was first elected to the board in 1938 and would serve until the spring of 1942. He was chairman for two of those years. He later served as chairman of the town’s Finance Committee from 1944 until 1959, a few years before his death in 1963. He was a projectionist at the Mahaiwe Theater for more than three decades, owned a Stockbridge Road gas station and garage, and provided assorted contractor-like services over the years.

As an elected official, Tracy was popular: In the 1939, 1940, and 1941 Selectboard races, he was the top vote-getter. He got his pilot’s license in 1934, learning at the airport he would soon own via lessons from Graf. In 1938, Tracy flew with Graf on a trip to Florida and back. (Graf had reportedly made the first nonstop flight from Connecticut to Florida in 1929.)

Also that year, during National Air Mail Week and commemorating the 20th anniversary of air mail, Tracy flew a batch of mail from Great Barrington to Pittsfield and was “the center of attention” as a crowd of more than 300 gathered at the airport to see him off in his Fairchild monoplane. He mostly carried specially printed envelopes for stamp collectors eager to mark the milestone.

There’s little evidence that Tracy did much at the airfield for the first year he owned it. He took over in July 1941, and the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December, which briefly halted general aviation. For security reasons, all planes at the field had to be dismantled, at least enough to be inoperable.

But things changed dramatically in August 1942. “Tracy Extending Runway At Airport 1200 Feet,” screamed the lead front-page story in the Eagle, detailing a project that had already been underway for a month. Tracy, doing some of the work himself, was clearing brush, grading, and seeding 20 acres of the airport’s property to develop an improved 1,200-foot north-south runway, likely approximating what would later be known as Runway 5/23. Tracy secured equipment and laborers and requested permission from authorities in Washington, D.C. for the materials—regulated during wartime—to build an administration building. Tracy told the Eagle it was “a huge project” that, when complete, would mean the airport would be the best in the region.

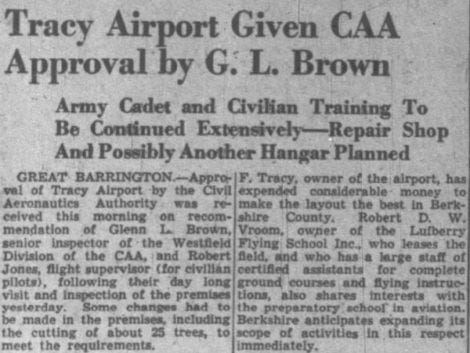

The driving force behind the sudden activity was two-fold: Earlier in August, the federal government allowed airport operations to resume as long as 24-hour guards were on-site. And Tracy had entered into an option to lease the airport to the Lufberry Flying School, owned by the perfectly named Robert D.W. Vroom, which would soon offer ground-school and flight training for civilians as well as those bound for the military and seeking a head start on learning to fly. “Get your start now in AVIATION at the Lufberry Flying School, U.S. Government Approved” read an advertisement that ran frequently. “Complete flight training and ground school training for private, commercial and instructor courses.” Tracy also expected an improved airport would “place it among the best for post-war activities,” he told the Eagle.

Tracy received swift approval from the Selectboard in December 1942 to cut down 29 trees that the Civil Aeronautics Authority ordered removed if the airport was to be certified and permitted to offer CAA-approved training. The project also involved lowering power and phone lines nearby. The board also approved Tracy’s request to store another 4,000 gallons of fuel in an underground storage tank, a permit that runs with the land in perpetuity.

The following week, when a nearby farmer complained that the lowered wires might interfere with his ability to remove hay and wood around his farm, Tracy said he’d work with the phone company on it. News coverage of the meeting summed it up this way: “The opinion was expressed there is a war on and that everybody must do his part.” The editor of the Courier, writing in the weekly’s “The Devil’s Pulpit” column, chimed in similarly: “I have no use for these quibblers who haven’t yet come to the realization that there’s a war on.”

Other than tree-cutting, there’s no record of Tracy seeking any permission for any of the work at the airport. Any and all of the work at the preexisting nonconforming property would have required either ZBA approval (the ZBA was formed in 1937), a re-zoning approved by town voters, or a special permit like the one BAE is again seeking again this month. None of the extensive news coverage of town boards, or of the airport, make mention of those approvals being sought or granted.

The busy war years

With his massive project complete and the Lufberry School in operation, the news was good. “Airport Future Looms Big to Flyers,” blared the lead story in the December 17, 1942 Courier. “Among the developments in South Berkshire in recent months, none exceeds in promise that of the expansion of the airport on the Great Barrington-North Egremont Road,” it began. In addition to “the fleet of training planes at the airport,” it said, “big plans are afoot for the airport not only during but after the war.” It noted that “during the past three months the Great Barrington airport has been vastly improved under the private ownership of James F. Tracy.” The Selectmen discussed the airport at its meeting that week, but not with respect to zoning: It gave the okay for six more trees to be cut down, joining the 29 others that the CAA initially required. (Lufbery was at the meeting and responded to a neighbor’s objection by claiming “two people” would die if the trees remained.) A week earlier, Tracy was “jubilant” at the CAA sign-off, which the Eagle described as essentially “throwing the switch for numerous plans that have been visualized but which couldn’t materialize” without the CAA stamp-of-approval for the airport.

Tracy certainly had experience with zoning issues, both as a member of the Selectboard and personally, and surely knew the rules quite well. He was able to get his own property re-zoned from residential to business so he could run his garage and also install gas pumps there. While on the board, he had a scuffle over zoning regulations with a Selectboard colleague, Paul C. White—who earlier opposed Wheeler’s proposal for a temporary town takeover of the airport—who, amidst an ongoing feud between the two board members, said Tracy’s gas pumps were located too close to adjacent residential properties.

Tracy’s response? To charge that White had himself violated the zoning bylaw by illegally remodeling a single-family house into a three-unit building and adding a porch, all in a single-residence zoning district. He claimed White’s violation “had been called to his attention” and triumphantly presented an unsigned, or what we would call anonymous, letter. White challenged him to identify who wrote the letter; Tracy dramatically signed it himself. Other than the ending, the exchange was reminiscent of last year’s mysterious e-mail from the still-unidentified “Alison B.” who alleged Selectboard members violated state ethics laws during Great Barrington’s battle over short-term-rental restrictions.

Ultimately, longtime town counsel Frank J. Brothers, who was a former Chamber and Rotary president, Berkshire Airways board member, and judge at the Southern Berkshire District Court, ruled that the building permit for White’s project—issued in 1934 by Henry J. Cairns—was not made “in strict accordance with the law.” Miffed by the decision, 10 days later White and the board’s chairman, James O. McCarthy, convened a “special meeting” without Tracy and unceremoniously fired Brothers. The reason given? “Difficulty over zoning laws.”

Flight training for the war

To meet the new federal requirement of 24-hour airport security and allow the resumption of operations, the Selectboard had also agreed to name six “special officers” as guards for Tracy’s airport. They were, conveniently, the owner of the flight school, Robert D.W. Vroom, and five of his school’s staff.

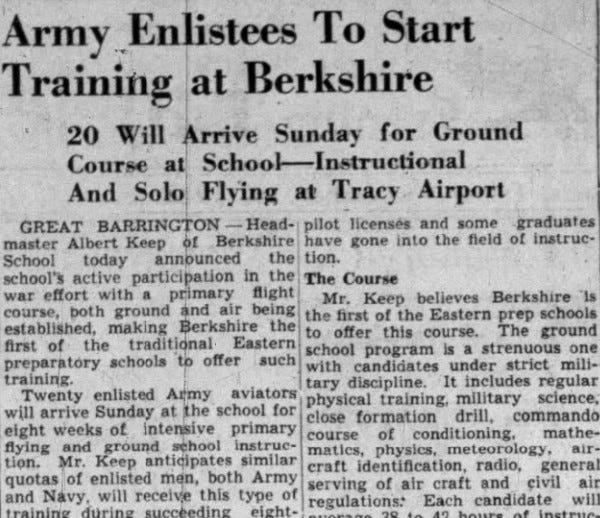

By fall of 1942, Vroom had partnered with Berkshire School on an eight-week program for enlisted airmen from the Army and Navy who would, in groups of 20 or so, take ground school classes at the school while doing flight training at Tracy Airport. A news report said the ground-school program also included “regular physical training, military science, close formation drill, a commando course of conditioning,” as well as aircraft identification and learning civil air regulations. As this program got underway, the school also began developing what would become the “Education with Wings” program, which operated for several years and taught Berkshire School’s enrolled students a similar curriculum, preparing them for military flying after enlistment. (The legacy of that program exists today and will be described later in this series.)

By January, army enlisted men dubbed “Victory Cadets” were taking classes at Berkshire and doing their flight training at Tracy Airport, graduating after completing the eight-week curriculum. The school’s headmaster, Alfred Keep, announced plans for an expanded program for its own students that would graduate them in three years—”abandoning long, wasteful vacations and intensifying its schedules”—and right into a commission in the air forces of the Army and Navy.

At that point Vroom had based at the airport “a fleet of ten 65-horsepower Taylorcraft dual-control training planes [that is] kept busy every day that flying is possible,” according to a story about the Berkshire program in the Eagle. Tuition for those enrolling in the three-year program was a third higher than for the regular four-year course, but it was, according to the headmaster, well worth it. “This may be the thing that will turn the scales in a dog fight over the Solomon Islands or Tokyo,” he said, so that it will be the enemy “who goes down in a burning plane while the Berkshire boy flier, because of his early training at school, comes out on top.”

By the spring of 1943, the airport’s flight school under Vroom was, weather permitting, flying from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m., with five instructors teaching cadets in shifts and five mechanics servicing the planes to keep them in the air. The Taylorcraft engines were checked every 12 hours of flight, given an oil change every 25, and, just as today’s training planes are, given a full, government-mandated inspection after every 100 hours in the air.

The flight traffic immediately around the airport was likely intense: There were strict flight rules both to keep the trainers from interfering with planes at the airport in Canaan, Conn., but also to comply with wartime regulations that required any flights beyond a short distance from the airport be charted and filed with authorities in Boston. So that kept the trainers within a few miles of the airport nearly all the time. In April 1943, the school reported logging 600 hours in the air.

These details contrast with some of the filings in the current Land Court zoning-enforcement case, which point to Walt Koladza’s references to having only a single plane or two when he took over in 1945. The reason was that Vroom and his Taylorcrafts left the airport when Koladza took over; he had to build up a new fleet of planes, which he did.

With that much activity and that many students, there were accidents and planes occasionally running out of fuel and landing in nearby fields. One of the naval cadets training at the airport crashed into a tree near the airport and then into the home of Floyd Kline, suffering minor injuries though his instructor, Ruth Ingall Castendyk, ended up at Fairview with more serious injuries. “In addition to a hole in the side of the house, a window and sash on the second floor were broken. This is the first accident at the recently opened school,” the Eagle reported.

With amusing understatement, Bernard Drew’s history of Great Barrington includes a mid-1990s interview with William L. “Bullet” Kline, who was 19 at the time of the crash into his family’s house. “Kline has considered the airport a good neighbor,” Drew wrote, “though an airplane did crash into his house in 1943.”

In June, 1944, 24 Berkshire School students were enrolled in the flying program as they prepared to enter the service upon graduation. And civilians were training there as well in the 65 horsepower Taylorcrafts. The airport also had a 225 horsepower Waco.

Things were going well for Vroom, so he can be excused for being a little too optimistic about what was next for aviation. He told the Great Barrington Rotary in the fall of 1944 that, within 10 years of the end of the war, everyone would be “operating airplanes as they now do automobiles.” He imagined that automobiles would disappear, replaced by what he called the “air-coupe.”

That level of activity remained steady and may have increased as the war went on. “Activities at Tracy airport, which are not limited to the Berkshire School course, have increased sharply,” the Eagle reported in June 1944, noting that additional improvements had been made “on the northeast end of the field” and that Tracy’s daughter Betty had passed 300 solo hours. A couple of years earlier, she was the first to take off on the newly improved runway, and she would shortly become the second woman in Berkshire County to, on her 20th birthday, pass her commercial-pilot examination.

Betty Tracy may also have helped cement aviation in general and local flight training in particular in Great Barrington’s consciousness. Her father bought the airport about four years after the disappearance of Amelia Earhart in 1937; Earhart was widely understood to have created wide interest in aviation and, importantly, reduce the fear of flying that many had. “Nothing impresses the safety of aviation on the public quite so much as to see a woman flying an airplane,” the groundbreaking aviator Louise Thaden famously said. With a woman at the controls, she said, “the public thinks it must be duck soup for men.”

Thaden was a pioneer alongside Earhart, winning the 1929 National Transcontinental Women’s Air Derby and setting the women’s record that year for speed, altitude, and endurance. And alongside co-pilot Blanche Noyes, she was the first woman to win the Bendix Trophy transcontinental race, in 1936, flying a Beechcraft C17R. (Her 1928 pilot’s license was signed by Orville Wright.) Betty Tracy would, as a local pioneer in her own right, go on to work at the airport in Canaan and become an instructor there.

With hundreds of military cadets pushed through flight training at Tracy Airport over the prior three-plus years, during a World War, it’s hard to imagine that zoning restrictions on the airport were on anyone’s mind—if there was even any awareness of the property’s status at all. That’s not to say there weren’t battles over zoning elsewhere in town. As described in an upcoming installment of this series, there were. It’s also unlikely that a former Selectboard chairman, who had been involved in his own zoning battles and who was deeply engaged in town affairs, didn’t know he was skirting the rules. Perhaps he assumed that after the war, when things returned to normal, he’d have to get those ducks in a row. But that day never arrived: As the war’s end was coming into view, he sold the airport.

The first news story about the pending sale to Connecticut-based F4U Corsair test pilots Charles Sharp and Walter Koladza referred to the latter as “Mr. Kloss,” and noted that he had earlier taught students at the airport in 1942-43. At that point, Koladza had 2,500 flight hours to his credit. “[Koladza and Sharp] plan to modernize the airport” and “establish a modern flying school,” the Eagle reported when the deal closed.

By the time Tracy sold to Koladza and Sharp in January 1945—they took over the following month—and Vroom made plans to close his flight school and sell or relocate its 10-odd Taylorcraft trainers, the airport had a newly improved runway, an administration building, and a new mechanic’s workshop, which, as the Hamer, Fredericks, and Fasteau zoning-enforcement request has argued since 2021, were not approved by the Zoning Board of Appeals, the Selectboard, or any municipal official.

The Koladza era begins

By all accounts, Koladza, just 26 years old at the time, got started quickly, even while still working during the week at Chance Vought, the Connecticut manufacturer of the Corsair. His earlier time at Tracy Field gave him a head start: A story in the Wallingford (Conn.) Record-Journal, a paper based just north of New Haven, said he was “well known by most of the local young men [in Great Barrington], who are now serving in the air forces of their country, most of whom he has had the pleasure of starting off on their careers in aviation.”

That it was still wartime was clear and present at the airport and across Great Barrington. That reality planted long-lasting, intertwined roots of aviation and the military at the airport. A little more than three months after taking over, Koladza hosted a bond-buying day at the airport, offering free plane rides to anyone who purchased a war bond. It was held on May 20, dubbed “I Am An American Day.” Just above a news item in the Eagle promoting that event was an article about the assumed loss of Lt. Gerould Giddings, the son of the local clerk of courts, who had been missing in action since the B-29 he was co-piloting disappeared over Tokyo during a nighttime bombing run in April 1945.

Within six months, Koladza was engaged to hometown girl Louise Decker, a graduate of Searles High School who ran a beauty shop and was secretary-treasurer of Koladza’s newly established Berkshire Aviation Enterprises. Around the same time, in something today’s airport advocates would cheer, a news item described 12 planes landing at the airport at noon in “the biggest array of airplanes ever seen at Tracy Airport.” After parking their planes, the pilots and their guests drove into town for lunch at Jack’s Restaurant.

A separate item on the same newspaper page noted the recent sale of a 20-room house and six acres of land on Baldwin Hill to Lt. William H. Weigle Jr. “of the Army Air Forces.” Weigle, who would later become an Egremont Selectman and a mainstay at GBR during a long career as a commercial pilot, was an outspoken defender of the airport through multiple controversies over the next 60-plus years.

All of this history tells the origin story of an airport that was birthed by a succession of men who played myriad roles in Great Barrington’s affairs and whose conflicting interests were rarely, if ever, highlighted or publicly addressed. That’s not to suggest they didn’t have the best interests of the town at heart, but rather to point out that it was a different time—and how that way of doing things laid down a path that leads directly to the current difficulties for the airport and those living nearby.

The airport’s past echoes into the present

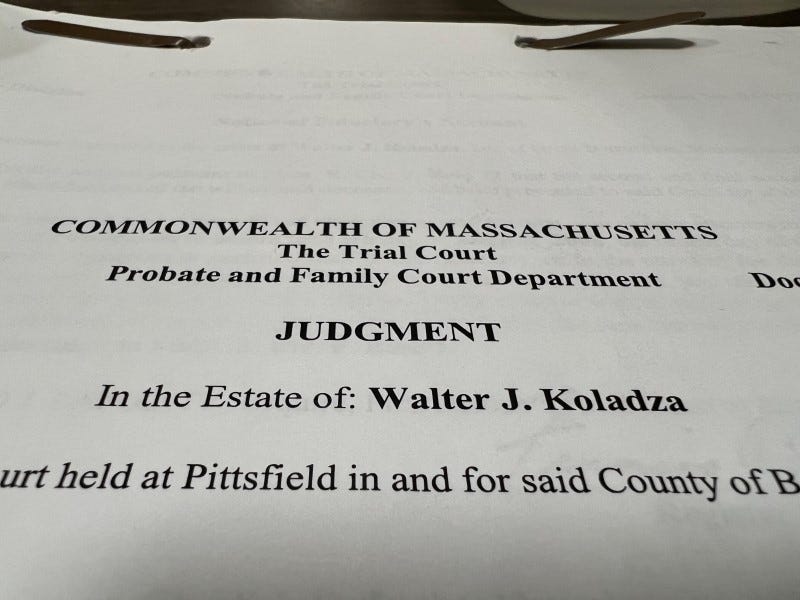

After Koladza passed away in September 2004, his last will and testament was a surprise to those who would be the airport’s new owners. The possibility that he would hand off the airport to some pilots had always just been an “idle threat” that no one took seriously, Rick Solan told me.

The transition was not easy, and the four-year probate battle with Koladza’s brother was rough. “That’s a bitter subject. It should have been something very simple, very easy,” Solan said. The four recipients—Solan, pilots Edward Ivas and the late Tom Vigneron, and mechanic John Guarnieri—together spent around $100,000 to keep the airport from going to Koladza, according to Solan.

“John [Koladza] didn’t care about the airport, he just wanted to get the money. He didn’t care who he sold it to,” Solan told me. The probate file shows legal action in both directions: Koladza arguing that the four men should pay the estate’s taxes on value of the airport, while the owners-to-be repeatedly challenged Koladza’s accounting of airport monies he was managing as the executor of the estate. In the end, those actions fell away, and the process formally concluded in October 2008.

Solan told me he knew nothing about the airport’s zoning status back then. “Walt kept everything close to the vest,” he said. As reported later in this series, a 1990 challenge to the airport’s operations, which Solan was connected to tangentially, suggests it may be a little more complicated. But there’s no question that the intricacies of the laws relating to preexisting nonconforming uses, and how the law applies to an airport in that category, are complex to the point of eyes-glazed-over numbness, and precisely why this story may end with precedent-setting court decisions. Which way they’ll go remains to be seen.

Up in the air, above the fray

Rick Solan loves flying; of that there’s no doubt. And all that comes along with being recognized for his mastery of the long-range, wide-body Boeing 777. “That’s the nice thing about flying the biggest plane in the fleet, it’s the most respect,” he told me a few weeks ago. From his time at Bar Harbor Airlines to today, he’s loved it all. “I never worked a day in my life. There was not one thing that I did not like,” he said.

It’s a career that’s brought him other rewards, too. When I asked what he liked most about his decades at American Airlines, he said, “The fifteenth and the thirtieth.” I looked at him, puzzled. “Pay day,” he said with a wink. Indeed, hiring and salaries for pilots ebb and flow with the broader economy and changes in the industry. But longtime pilots do very well, protected by strong unions. And the last couple of years have seen a substantial increase in the demand for pilots and other workers across the airline industry. An aging pilot corps combined with early pandemic uncertainty that meant early retirement packages and little-to-no new hiring had thinned the ranks. That contributed mightily to what travelers experienced during last year’s many chaotic periods of delayed and canceled flights.

That need and the resulting dramatic increase in airline-pilot salaries has fueled at least some of the demand for flight instruction at Great Barrington Airport, which is now among only a handful of flight schools in the region. Indeed, the closing or reduced activity of nearby flight schools in Pittsfield, North Adams, and Hudson has been a boon for BAE’s business.

Today BAE has five full-time (including the Solans) and three part-time flight instructors, three full-time mechanics, two line boys, and Terri Andersen, who has been BAE’s business manager for more than five years. Joe Solan told me last summer that, between just his father and him, they often have 10 flight-school students in a day. That’s not including all the students taken up by the other instructors. They’re also trying to make available the expensive project of flight training to those who, like Rick Solan a half-century ago, need some help: Last year BAE gave away $15,000 in scholarship grants to young people in the region toward flight-school expenses. This spring it will award another $15,000. And Solan sometimes pays for his students’ lessons out of his own pocket, several people connected to the airport told me.

Yet that increased level of flight-school activity—which fulfills Rick Solan’s dream of helping others write a chapter about flying into the story of their lives—is likely to be at the heart of the special-permit discussions that begin shortly.

A complicated mix

Over many months, my long conversations with Solan easily revealed the two parts of his life at the airport. When talking about his career, or teaching, or his son, or anything at all related to airplanes and aviation, his enthusiasm fills the room. He’s a pilot in his element. But turn the subject to zoning, or lawyers, or concerns about leaded avgas, or the years-long challenges facing an airport in an R4 residential-and-agricultural neighborhood, and things change in a moment. It’s like an Instagram filter called “existential fatigue” gets applied: His demeanor stiffens, his eyes look flat, any playfulness vanishes. Such is the complexity he faces in a retirement that’s far different than what he planned, when he thought he and his wife would travel and spend time together, freed from the schedule of a commercial pilot.

“I’d be a hell of a lot richer and a lot happier if I didn’t have the airport,” Solan told me wearily one morning, after I quizzed him about the probate battle and some of the other challenges since. “If it wasn’t one thing it’s been another after another after another.” There had been other moments like this in our talks, but this was a rare instance when he seemed truly weighed down by the struggle.

But just as it did the other times, the moment soon passed and Solan brightened. “It’s because of my love of the airport that I’m here,” he said. “I always want to make sure this is an airport. So if there’s some other person like me that can’t afford to fly, we make sure they can get their license.”

Opponents of lifting the airport’s zoning restrictions point out that any change will be permanent; a special permit runs with the land. They think the airport’s operations already far exceed what should be allowed. But they also say that even if you love Rick Solan and today’s BAE, and admire his passion for teaching, and his son’s dedication, and the charity events, and the toy planes handed out to visiting kids, and the cadre of passionate flight instructors who care deeply about what they do, the future is uncertain. A new owner in a year or 10 or 20 could be better or worse. And there’s no way to know.

NEXT: In part three, just how busy is Great Barrington Airport?