Plans for culinary training and a health-and-wellness center were scuttled after the town awarded a $250,000 restoration grant. The town committee that recommended the grant has questions.

∎ ∎ ∎

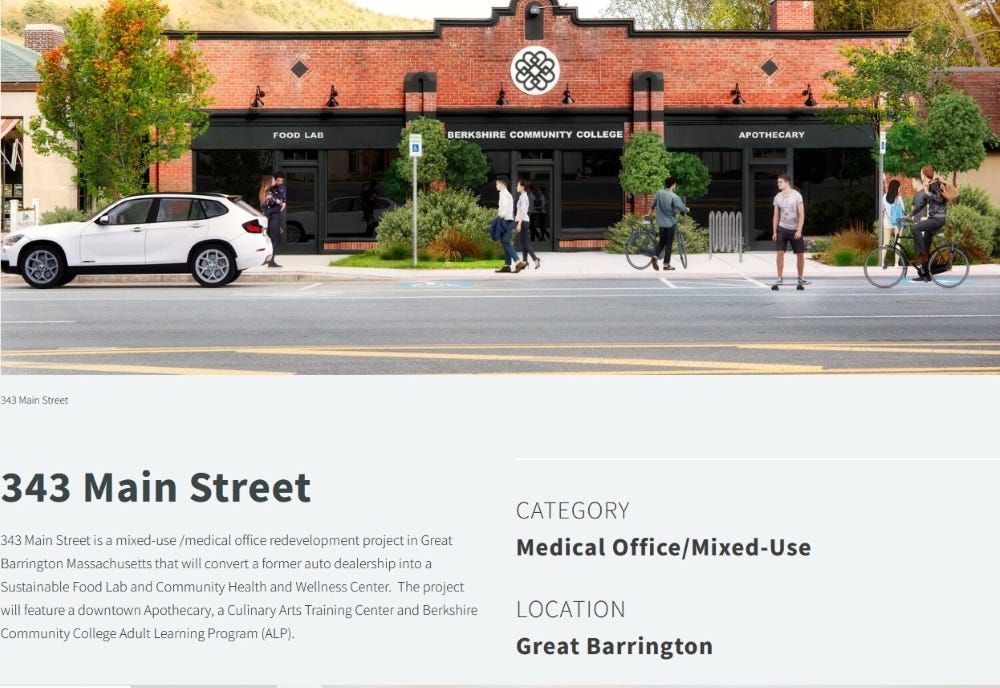

In late August, after that white “Alander” safety fence went up around the former Berkshire Community College (BCC) building at 343 Main Street directly across from Town Hall, developer Ian Rasch’s construction team began internal demolition and work to repair and restore the building’s historic façade.

Built in 1922 and designed by Pittsfield architect Joseph McArthur Vance, the building sits on land once part of the adjacent Edward Searles estate, now the residence of artist Hunt Slonem. It was built as the Whalen & Kastner Garage for an early Ford dealership previously located on Railroad Street. It would later become the home of Mahaiwe Motors in the 1950s, Whittaker Motors auto sales and service in the 1960s and 1970s, and then other businesses before it was purchased by BCC in 1987 for $510,000.

The original construction was completed by J.R. Hampson & Co., a Pittsfield company whose frequent Berkshire Evening Eagle advertisements in the 1920s included copy like, “We build character buildings, the kind which prove their wonderful character year after year and prove steadfast friends.”

To become steadfast friends with this particular building, Rasch approached BCC with an unsolicited offer, according to reporting last fall by The Berkshire Eagle. He has since told me that with plans to “keep going” in acquiring and redeveloping downtown buildings, he’s “probably spoken to every landlord in Great Barrington” about their properties. Many phone calls followed with Eugene Dellea, board president of the BCC Foundation, and discussions continued throughout 2020 and 2021. The sale closed on December 16, 2021.

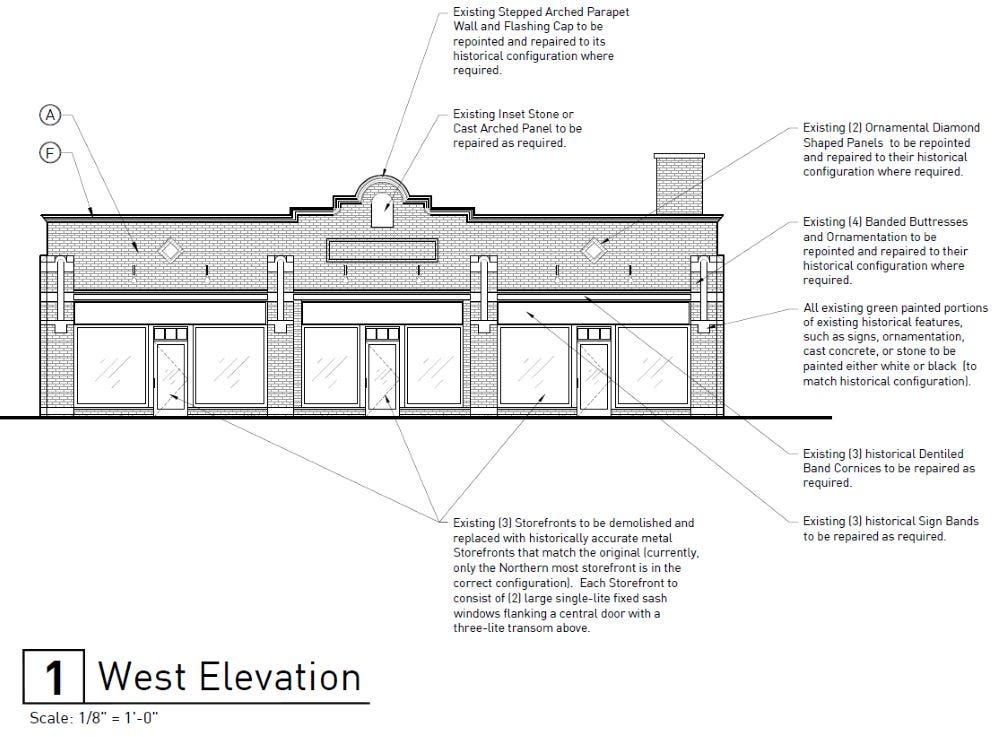

Rasch’s plans for the building were made public in a December 2021 application for $250,000 in historical-preservation funds from the town’s Community Preservation Act (CPA) fund to pay for the external restoration of the building. These grants are made each year with monies raised from a three percent property-tax surcharge and a yearly distribution from the statewide CPA Trust Fund. The awards are limited to four areas: historical preservation, affordable and community housing, preservation of open space, and recreation.

The town’s Community Preservation Committee, established by voters in 2012 and made up of members from various elected town boards and a couple of “citizens at large,” reviews applications each fall and winter. It then makes recommendations to be approved by voters at town meeting. Grant-making must align with the committee’s priorities as detailed in a Community Preservation Plan.

As part of the $5.25 million redevelopment project, Rasch lined up $1.35 million in private-equity investment and $3.15 million in mortgage financing from Lee Bank. As detailed in his CPA application, the $750,000 gap would be filled with the CPA funds and, possibly, $500,000 from MassDevelopment’s Underutilized Properties Program (UPP), a competitive state-funded grant program that provides funds “to achieve the public purposes of eliminating blight, increasing housing production, supporting economic development projects, [and] increasing the number of commercial buildings accessible to persons with disabilities.”

While for-profit developers like Rasch’s Alander Group are eligible for taxpayer-funded UPP grants, they “need to make clear the public purposes advanced by their proposed funding request.” That’s according to the eligibility requirements, which describe the “public benefit” as “a key review criteria.”

Until they vacated this summer, the building was home to BCC offices and classrooms for its Adult Learning Program; a Community Health Program (CHP) dental practice; and Elements, Mt. Washington resident Jill Schwartz’s 6,000 square-foot jewelry-production studio on the building’s lower level. Rasch bought out Schwartz’s lease in February; she had been in the space for nearly a quarter-century.

Rasch planned to gut-renovate the building and create what he called a “Sustainable Food Lab and Community Health and Wellness Center.” As described in the CPA application, “The health and wellness focused nonprofit tenancy will expand health care access to all, provide educational and job training opportunities, support and create connections to the local agricultural community, and provide economic development benefits by creating and retaining jobs, both temporarily during construction and permanently during occupancy.”

BCC’s south county offices and classrooms and CHP Dental would remain. They’d be joined in the renovated building by Volunteers in Medicine (VIM), a healthcare nonprofit relocating from its smaller South Main Street facility, and a new Berkshire Health Systems (BHS) pharmacy. And a marquee tenant would be a new food-related enterprise called Sustainable Food Lab Berkshires, featuring classrooms and two culinary-training kitchens, according to Alander’s architectural plans submitted with the application.

“Sustainable Food Lab Berkshires will occupy the public-facing portions of the ground floor, where it will run educational programs, workforce trainings, culinary incubator space, and a retail restaurant promoting regional food self-sufficiency,” the application promised.

With a beautiful, historically restored exterior and filled with nonprofit tenants, by late 2023 the building would be “an attractive and important resource for health and food-related uses,” Rasch wrote, describing the many public benefits delivered by the project. “This mix of tenants will create new job opportunities as well as retain existing jobs, develop and expand a forum for equitable job training and skills development, and increase wellness access for the region.”

Letters of support came from State Rep. William “Smitty” Pignatelli and then-State Sen. Adam Hinds. Their letters shared sections of identical language—likely provided by Alander and not uncommon in support letters—touting the value of bringing together healthcare and education nonprofits under one roof, “all while encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship and training a skilled workforce.”

Hinds, who left the state senate last month to become CEO of the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, also wrote, “It is also my understanding that all the nonprofit tenants have committed to the project.”

In the end, a “Sustainable Food Lab and Community Health and Wellness Center” was not to be. Changed plans and priorities, increased build-out costs, and higher proposed rents than expected led some tenants to drop out of the project by late spring, Rasch and the prospective tenants told me. So Rasch had to pivot.

“Part of [Alander’s] responsibility is to try to figure out how to adapt as organizations [and] businesses are forced to adapt, shrink, and re-envision their plans,” he told me in early October. “It was a painful—and expensive, mind you—process to go through this whole transition. I mean, we had [letters of intent] from everybody. We had a commitment, we financed the project, everything was set, and then everyone started falling by the wayside and pulling out.”

He shared a story about 47 Railroad’s widely publicized plan to feature a new restaurant, The Fox, helmed by White Hart Inn co-owner and renowned chef Annie Wayte that would occupy most of the renovated building’s first floor. Plans were advanced, a lease was in place, and engineering and architectural plans were complete. “And then it just blew up,” Rasch said. The restaurant project cost each side more than $100,000 and could have resulted in litigation. Instead, he said, the parties agreed to end the relationship “with a handshake” and walk away. (Wayte did not respond to an email inquiring about the fate of the project.)

During his 20 years of real-estate-development, Rasch said he’s seen this often. “As quickly as people line up and commit to tenancies, they fall apart.”

“Let’s put it this way: Every project I’ve ever done dies 15 times between when you start and when you finish,” he said. “And you have to figure out how to be nimble enough and committed enough and persevere through whatever happens and try to adapt. It’s unfortunate, but it’s pretty typical for these types of projects.”

While prospective 343 Main tenants were reconsidering, he was simultaneously in negotiations to acquire the Mahaiwe Block for redevelopment into 22 luxury apartments. His market study for that project suggested strong demand for more of the apartments he’d built at 47 Railroad, now achieving New York City-level rents of $2,500 for a one-bedroom and $3,500 for a larger two-bedroom unit. And a new market study he commissioned in May to examine the potential for residential apartments at 343 Main was similarly encouraging, he told me.

Given the need for more housing, and his vision for projects he argues will contribute to a vibrant downtown, Rasch decided apartments would be more valuable.

“I thought, why aren’t we doing housing at BCC? I mean, again, from a community-development perspective, people living downtown is much more interesting than just office space that’s occupied for a portion of the day and closed out.” He said there is plenty of space on the outskirts of town for the organizations originally planned for the building.

He also reiterated the benefits of what he says will be mixed-income downtown housing and the economic-development value of rehabilitating an underused property on Main Street.

“I think at the end of the day, net for Great Barrington, having a mixed-income housing community is by far a better use of the space,” he said. Whether and how many units are made available to income-limited residents, and at what rents, remains undetermined. But Rasch has made a public commitment to that effort, with a goal of 20 percent of his apartments at 343 Main and the Mahaiwe Block reserved at some level of affordable housing.

He also pointed to economies of scale that will improve his bottom line. With two similar redevelopment projects underway at the same time just yards from each other, he said he’ll purchase things like drywall, heating and cooling equipment, appliances, and other materials in larger quantities and with additional discounts.

So, what happens to the CPA grant for historic restoration of the façade—a small and discrete portion of the overall project, he points out—of a building pitched to town voters as a nonprofit health and wellness center but that became something else? Could anyone have reasonably predicted the plan might change so dramatically?

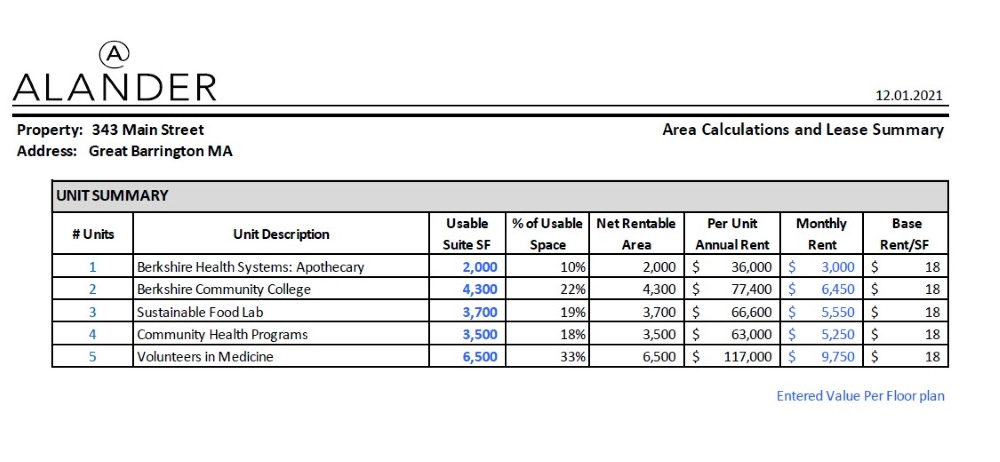

In what may now strike some as inappropriate overstatement, Rasch’s CPA application left little room to doubt the project would go forward as described. It stated that all five prospective tenants had made firm commitments to the project: “The tenants are all committed—please refer to the attached term sheets,” it said in one section. The project “promotes economic development both through its committed tenancy and in addition to its job creation and retention,” it said elsewhere. “The committed nonprofit tenants are an additional demonstration of community will for the project, and the extensive services that they will provide to the town,” it repeated.

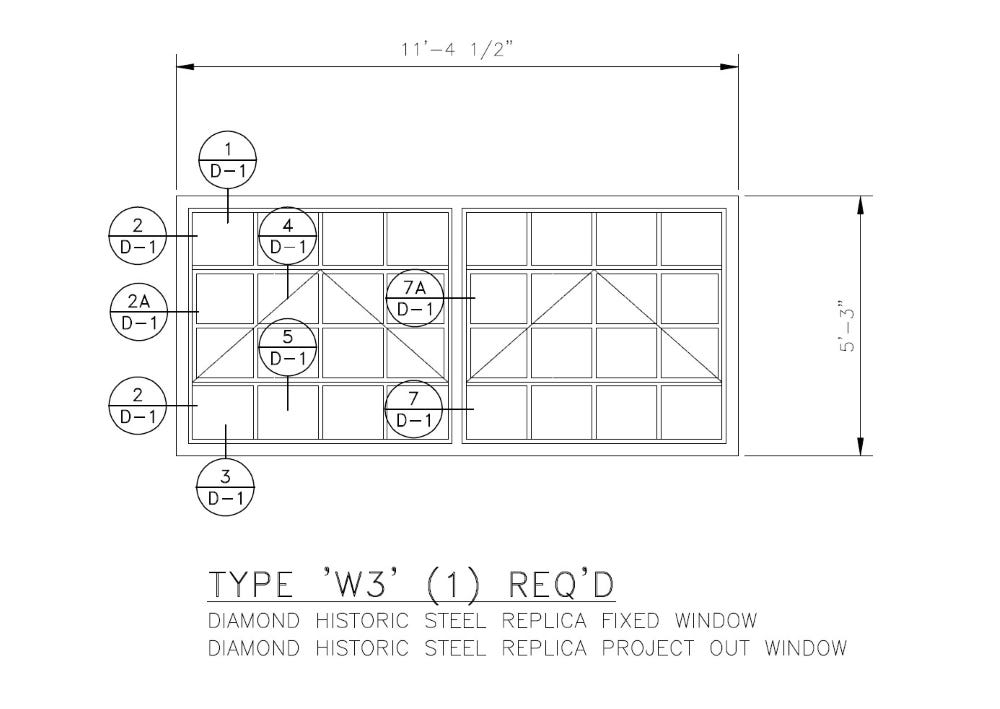

Yet the five letters of “Intent to Lease Real Estate” all state, in the first sentence, that they are nonbinding. Curiously, the rents to be paid by the nonprofits were also substantially lower in the application narrative than what was detailed in the attached letters of intent (LOI). Those letters had all been signed more than six months earlier, perhaps as Rasch was lining up bank financing and private-equity investors for his project.

A rent summary early in the application showed all tenants paying $18 per square foot (per year), an attractive rate that’s lower than retail and commercial rents for high quality renovated space in Great Barrington’s downtown corridor.

Yet the LOI for VIM, for example, said it would not pay the $9,750 monthly rent presented in the summary, but quite a lot more: $15,000 per month, or nearly $24 per square foot. That would be a total of $180,000 per year, not including its share of charges commercial tenants pay for things like common-area maintenance, snow plowing, and other expenses. BCC’s letter of intent to lease 4,500 square feet reflected a rate of nearly $27 per square foot. And the monthly rent for Sustainable Food Lab Berkshires was nearly 40 percent less in the application narrative than in its LOI, which called for the nascent organization to spend fully $108,000 per year on rent.

Rasch told me earlier this month that the various and conflicting numbers represented “a moment in time” during an evolving project.

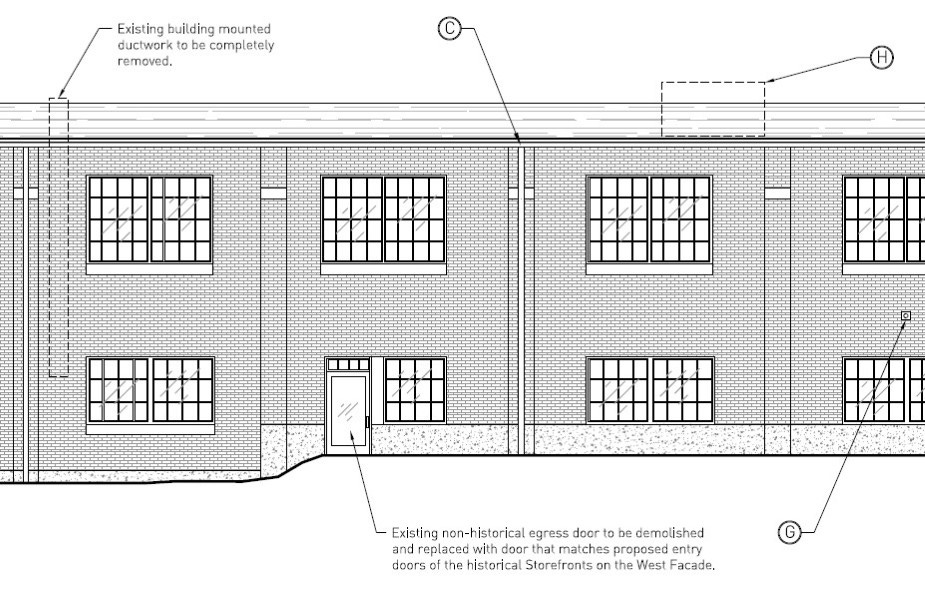

Architectural plans included in the application were also inconsistent. Some of the drawings, dated May 2019 and labeled “South County Center, BCC,” showed a top-floor plan with four separate kitchen areas and a “flexible event space” laid out like a restaurant.

Those plans, drawn by an Adams, Mass. engineering firm, included detailed schematics for electric, water, and venting systems appropriate for commercial kitchens. They also described “proposed kitchens and BCC’s planned expansion into the main floor’s vacant space” that was substantially different from Alander’s own architectural plans included the dense, 147-page CPA application—one that may not have been reviewed closely by all committee members. The 2019 plans appear to be for a culinary-school project under consideration by BCC before it decided to sell the building to Rasch.

It seems no one on the CPC noticed the conflicts or discrepancies before recommending the grant to town meeting. Karen Smith, then a member and now chair of the committee, asked Rasch if the proposed rents were enough to cover the mortgage, according to minutes of a January 6, 2022 CPC meeting. He assured the committee they were. Because video recordings of CPC meetings are not retained or posted to the Town of Great Barrington’s YouTube channel, or shared on Community Television for the Southern Berkshires (CTSB)’s website, it’s unclear which proposed rents were being discussed.

When I spoke to Smith last month, she couldn’t immediately recall why she asked about rent revenue at a meeting that, she said, took place nearly 10 months ago.

The CPC is certainly eager to re-examine the matter. On September 15, the board discussed the project’s change of use from a wellness center to upscale residential apartments. At least three members voiced concerns, including Selectboard member Leigh Davis, CPC vice chair Tom Blauvelt, and Smith.

Smith agreed that Rasch should come back to the committee while also pointing out that the grant was for historical restoration of the outside of the building. “A façade is a façade is a façade,” she told her colleagues. “Whatever happens inside the building, I’m sure the townspeople would like to know [about it] going from wellness to housing. But the intent of the grant was the outside,” she said.

In our phone conversation, Smith was clear that voters should weigh in. “My feeling is, transparency-wise, that because the project has changed, the town meeting should get a chance to speak up on it,” she said. As she pointed out at the recent CPC meeting, “The historic preservation issue has not changed one way or the other.” But given the priority the committee gives to the need for affordable housing, she told me that the moment also presents an opportunity.

“From my perspective, if he would be accommodating and put some affordable housing in there, then perhaps he could qualify on two counts, not one,” she told me.

Tom Blauvelt, who works next door at Wheeler & Taylor and therefore recused himself from the January discussion and vote, told the committee that the application approved by town meeting is “totally transformed into a whole different use. We deserve to take another look at it and perhaps it needs to go back to town meeting,” he said.

Blauvelt told me in a recent phone conversation that the project likely still qualifies for the historical-restoration grant, but, like Smith, he thought the committee should consider whether voters might want to weigh in. “We think maybe out of an abundance of caution we invite [Alander] back and just brief the committee,” he said.

Despite the committee’s discussion of a possible “re-vote” or perhaps sending the matter back to town meeting for reconsideration, at this point it’s unclear who’s empowered to take action on an already-approved grant. Or what that action could be.

When I spoke earlier this month to Chase Mack, communications director for the Community Preservation Coalition, an organization that highlights the positive impacts of local CPA-fund investments across the Commonwealth, he pointed out that once a CPC grant recommendation is placed on a town-meeting warrant, it’s treated like any other proposed expenditure. There’s no CPA-specific procedure to reevaluate an already-approved grant award. Mack wasn’t aware of any similar situation, which he called “hazy,” since the CPA was enacted by the legislature more than 20 years ago.

Chris Rembold, the assistant town manager and director of planning and community development who also serves as the CPC’s staff liaison, confirmed in an email that there is no statutory authority or process for the committee to vote again or send the question back to town meeting. He also said that the town and Alander haven’t yet entered into a required grant agreement, so no funds have been disbursed.

It seems that short of some unlikely grounds for legal action, Rasch would have to volunteer to re-apply in the new CPA grant cycle that begins this month. The committee has invited Rasch to attend its next meeting, set for November 1. He told me he’s looking forward to the discussion. Given his plans to apply for additional CPA funds to help subsidize affordable apartments in 343 Main and the Mahaiwe Block, it will be interesting to watch the conversation unfold.

Still, Rasch is adamant that the already-approved grant for exterior historical restoration should stand, regardless of what’s going on inside the building. He called the change of use “immaterial.”

“The facades and the streetscapes of this town and the associated buildings have public benefits. They’re part of the historic fabric here,” he said. Indeed, the building—following a successful application filed by an Alander consultant in 2021—is recognized as historically important by the town’s Historical Commission. That designation is required for the building to be eligible for CPA historic-restoration funding. The Massachusetts Historical Commission had already confirmed the building’s historic status in 2017.

“The quid pro quo, if you will, is that we spend the time and money investing in restoring the facade, restoring the windows to the National Park Service standards [for historical restoration], which is expensive,” he said.

He said that using generic, historically incorrect windows in the building would cost around $98,000, while using the ones he presented to the CPC will cost $275,000. And that along with the CPA grant comes a permanent restriction that requires any future external renovations to adhere to strict historical-restoration standards. “Not what you think is historical,” Rasch said, “but following the guidelines of the National Park Service.”

He also pointed to examples of CPA funds awarded for other historical-restoration projects across the commonwealth, including some to private developers. He sent me a summary of arguments he’s likely to present to the CPC, built largely around the need for more housing and the value of historic restoration of an important downtown building.

Whether the committee will see it that way, and what they can or might do, remains to be seen. “I hope they will still be excited to fund it,” he said. “The twist now is that it’s a historic-preservation project, but it’s also going to be a mixed-income housing project. It’s trying to fill that region-wide gap for mixed-income housing.”

When I asked Rasch if he thought the committee would have viewed his application less favorably if it was for historical restoration of the exterior of a building that contains mostly large, expensive rental apartments, he stood firm.

“If it had, then from my perspective they’re not fulfilling the obligations of what the funding source”—the bucket of CPA funds for historic preservation—“is supposed to be used for. Because it is a public benefit,” he said. “It’s historic preservation, end of story.”

As the committee re-examines the grant, it will have to consider that his application leaned heavily on enticing plans to provide expanded health, wellness, and vocational-training services to the community. And that those clear public benefits of the overall project were likely an easier sell to the committee, and town meeting, than a beautifully restored downtown building featuring luxury apartments—even if he can make two or three of them affordable via additional CPA funding or subsidies he may seek from other sources.

Overall, Rasch feels the building’s change in use makes sense for both Alander and the town. “This was a very carefully calculated change that was forced by market conditions, like CHP and Volunteers in Medicine and their change of plans. But also, we are very actively involved in this town and understand the need for housing,” he told me. He re-engaged his consulting firm for that new market study and had discussions with his investors and mortgage lender before pulling the plug on the original plan and moving forward with the new one.

“So, longer term I think it’s exactly what you need there, particularly because it butts up against the [Berkshire] Co-Op and there’s people living in the top two floors of the Co-Op building,” he said. “I think it’ll add a lot of vitality to Great Barrington.”

NEXT: So what happened to Sustainable Food Lab Berkshires and the nonprofits that planned to occupy 343 Main Street? In part five, more details about how plans unraveled for food-focused workforce training and a health-and-wellness center.

(This series first appeared in The Berkshire Edge.)