With other similarly challenged communities around the country taking far bolder action on housing, when will Great Barrington and the southern Berkshires do the same?

∎ ∎ ∎

When I first spoke to George Ruther, the longtime Vail, Colorado urban planner who now serves as the resort community’s housing director, it was late July and he was getting ready to board a plane to—of all places—Massachusetts.

A compelling speaker on ideas to address the housing crisis, he was headed to a conference on Cape Cod to share what he’s accomplished in Vail through an innovative deed-restriction program that can help preserve housing for local workers in tourism-based, second-home-heavy communities from Colorado, to the Cape, to right here in the Berkshires.

“When we started Vail InDEED, we really weren’t sure what was going to happen,” Ruther told me during that first conversation, referring to the signature program he launched in 2017. “Other than we knew we had to do something. We knew we had to try something different than we had been trying.”

That something different is the purchase of deed restrictions on properties in Vail that require homes and apartments to always house at least one person who works an average of 30 hours a week in Eagle County, where Vail is located. For somewhere between 15 and 20 percent of a property’s value, the town invests to preserve housing inventory exclusively for those who work in the community. That includes more than just the tourism industry’s restaurant and seasonal ski-resort workers, but also Vail’s nurses, firefighters, teachers, and all the others who make up the year-round community.

The program is simple, which Ruther argues is key to its success. Either at the time of a real-estate transaction, or if a property owner wants to join the program in exchange for immediate cash for improvements, retirement savings, to pay off a mortgage, or to spend on a child’s education, the town negotiates a price and cuts a check. From that point forward, at least one member of a household in a deed-restricted house or rental unit—multi-unit housing is included in the program, naturally—must be a local worker.

Take for instance a couple purchasing a $500,000 home. Under the program, the town of Vail would effectively—and sometimes in actuality—be at the closing table, handing over a check for perhaps $75,000 to deed-restrict the property in perpetuity. Or imagine an existing owner of single- or multi-unit housing who wants to take out some equity to replace a roof, renovate a kitchen, or update a rental apartment. They just fill out a simple online form, wait for the town to appraise the property’s fair market value, enter a negotiation, and a few weeks later get a check. And just like that, housing for local workers has been preserved.

Unlike affordability restrictions, with Vail InDEED there’s no appreciation cap placed on the property. That means when the owner is ready to sell, the price can be whatever the market will bear. That housing remains available to anyone who works there, no matter their income: Brain surgeon, office manager, or police sergeant, they just need to work in the community. That requirement does keep prices down, Ruther told me, but it’s not written into the deed.

There’s accommodation for those nearing retirement age, and discussions are proceeding about how to adjust to the shift to COVID-era remote work. The program already makes some exceptions for temporary work assignments away from Vail.

What’s happened over time, Ruther told me, is a bifurcation in the housing market between the open market and the growing inventory of rental and for-sale properties reserved for resident workers. Those all-cash, no-contingency offers from out-of-towners no longer push aside locals who need permanent housing in the community where they live and work.

My conversations with Ruther this summer and fall made clear he’s given his pitch for Vail InDEED more than a few times. It’s hard to imagine a better, more thoughtful advocate. He tells an important story not just of how a community took a chance on a novel idea, but also—and importantly—how and why Vail also reorganized its approach to addressing the housing crisis. Both were needed, Ruther said.

Many in Vail spent years talking about the housing challenge, and trying some things, but in the end, Ruther said the town council accepted that it couldn’t fully address the problem on its own. It had a lot to do on many fronts; ten minutes to discuss housing at the end of its meetings wasn’t enough.

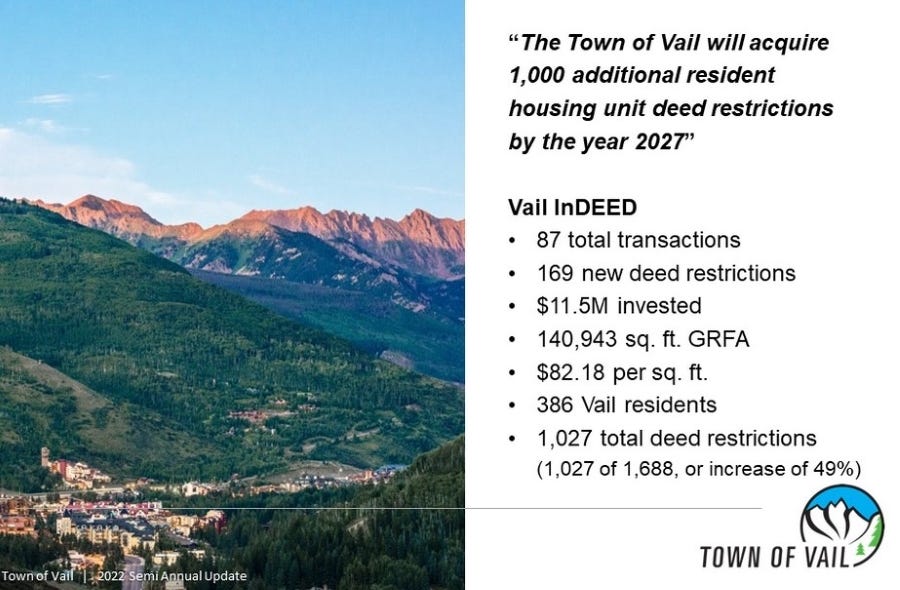

So a group of stakeholders went through a six-month planning process and produced Vail Housing 2027, a clear and simple 16-page strategic plan that outlined the need for resident housing, a goal of 1,000 new deed-restricted properties in 10 years, and a plan to get it done. Not just lists of ideas to ponder, or more master-plan-style language that defines goals and aspirations unhindered by tasks and timelines. Instead, they had a rubber-meets-the-road plan for urgent action.

It delegated authority to a freshly empowered Vail Local Housing Authority peopled by appointed members with housing-related expertise to act on behalf of the Vail Town Council and start purchasing resident-worker deed restrictions. It also created a simplified decision-making structure that required only twice-annual reports back to the Council. “A new decision-making structure is needed to get better results,” the plan said, arguing that a housing-focused entity had to be “singular in mission and focus” and “empowered and results-oriented.”

Ruther told me this was a critical change. “Our focus on housing was still sitting embedded within a department or a team within the community development department. And a decision was made that we had to put the time, attention, and resources to addressing the issue,” he said. That led to a position of housing director, which he now fills.

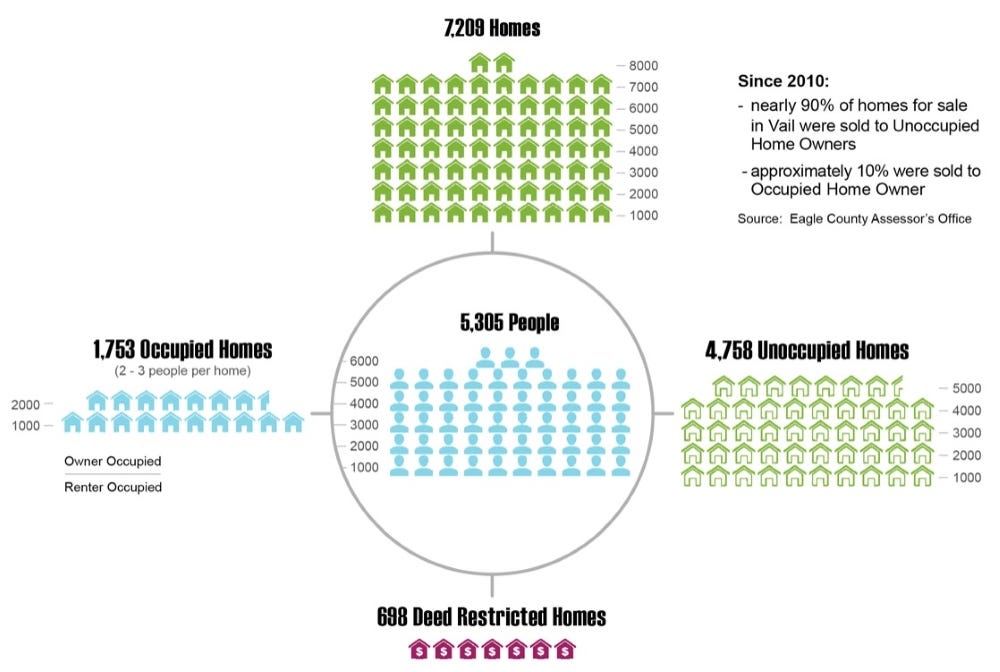

As part of his pitch, Ruther showed the council that over the prior six years, nearly 90 percent of homes for sale in Vail were acquired by “unoccupied home owners,” which includes part-time residents and properties used exclusively for seasonal or short-term rentals. This appeared in a stark and effective chart that demonstrated the clear need for 1,000 additional homes reserved in some way for working residents.

The plan argued that an action-oriented decision-making structure and well-funded deed-restriction program would serve the top priority of a 2016 community survey: “Focus on housing for middle income and service worker households in vital support roles.”

And that led to the plan’s concise, two-sentence mission statement: “We create, provide, and retain high quality, affordable, and diverse housing opportunities for Vail residents to support a sustainable year-round economy and build a vibrant, inclusive and resilient community. We do this through acquiring deed restrictions on homes so that our residents have a place to live in Vail.”

Ruther asked the council for $500,000 to start; he spent it in eight weeks. So he went back and received another $1.5 million. And last year, voters in Vail approved a half-percent sales tax to create a permanent revenue stream for the program and other housing initiatives. In fact, it produced so much revenue in its first year that, under Colorado law, the town will ask voters next week for permission to spend all $5.4 million from the levy on housing efforts.

More recently, as Ruther saw a rise in cash offers that were squeezing out locals, the Town of Vail decided to become one of those cash buyers. Still a nascent program, and one that Ruther concedes requires more staff time and overhead, Vail has started to buy properties it believes are a good fit for its resident-worker needs just like any cash buyer in the market. That’s attractive to both real-estate agents and sellers looking for a quick sale. After the transaction closes, the property is immediately deed restricted under Vail InDEED and sold at a lower, deed-restricted price.

On average, Ruther told those gathered earlier this summer at the One Cape conference that Vail has spent an average of about $68,000 per deed-restricted housing unit—and that’s in a housing market with a higher median home value than in the southern Berkshires. Nearly 400 Vail residents now live in housing reserved under the program. When considering time-to-market for new affordable-housing development in our region, and skyrocketing construction costs, that’s a bargain. And it leverages existing housing stock immediately, with no abutters with lawyers or NIMBYs hollering at Citizen Speak to hold back what’s needed. As Ruther told me, the only difference for neighbors is that they’ll start to see lights on in the house next door. “Because someone from the community is actually living there,” he said.

Ruther credits local government for taking a chance. “I’m fortunate to work for an organization that is willing, especially when it comes to housing, to think differently, be bold, and [that] allows our housing department to fail forward,” he told me. “As long as we’re trying, we’re going to try anything to address this issue.” As for the council’s decision to delegate authority and resources, he said, “The real message is the acknowledgement that a body of policymakers didn’t have all the answers. There are people that are better at this.”

Ruther, who previously worked for the town on development related to Vail Resorts, said another realization was acknowledging that both words in “resort community” need attention. “We did a really good job of improving the resort side of ‘resort community,’” he told me. “In hindsight, we probably could have done a far better job of also focusing on the community side of resort community.”

Describing what drives efforts in Vail, he shared a reality for resident workers that will sound painfully familiar to those in the southern Berkshires. “Once you got to a certain place in your life, and circumstances changed, you were faced with a choice of living in a one-bedroom apartment or condominium with two kids and a dog and a spouse,” he explained. “Or you packed your bags and drove 40 miles down valley and you lived in [the town of] Eagle. And then there was another piece of our community, you know, just gone.”

Importantly, Ruther’s work to create, implement, and push forward a 10-year plan didn’t just happen in his head or even in his office. “I spent a fair amount of time out in the community talking to people,” he told me. “I jokingly say I spent $3,000 on coffee over a very short period of time because anybody and everybody who would talk to me, I would take out for a cup of coffee. I was trying to understand their perspectives. We talked to the lenders in real estate, appraisers, and real-estate brokers and home builders and businesses large and small. I mean, you name it, we talked to everybody who would talk to us about it.”

One of the first to work on the project with Ruther was Steve Lindstrom, a longtime Vail resident who had served for decades on a local housing board. Lindstrom arrived in Vail after college, living the ski-bum life before drifting into various businesses and finally, in 1983, starting a chain of movie theaters with his wife.

When I spoke to him in July, he told me about his weekly coffees with Ruther where they kicked around ideas about how to tackle the housing problem. And the problem was clear. “Over time, the ratio between typical wages and properties has been just magnifying. So what used to be a multiple of whatever is now a multiple of 10 times,” he said, pointing to the same troubling wages-versus-housing-prices divide that’s common in tourism-based economies today. “So it’s only been these last several years that people are waking up to the fact that, you know, our restaurant service is not so great. And these [businesses] are having to close. And ski mountains, they can’t run every lift because they don’t even have lifties to do it. They’re finally realizing there is some consequence of not having people living here.”

Lindstrom said people have embraced Vail InDEED and understand its importance for the entire community. “It’s a mindset change. Because everybody thinks of deed restrictions as something for ‘those people’ instead of ‘us.’ And this is really for us. Everybody who lives here, if you work here, you’re qualified.”

With decades of experience grappling with a housing crisis, Lindstrom concisely summed up what a community needs to tackle its housing challenge. “You need three elements to start making progress in housing. You need land, you need funding, and you need alignment,” he said, suggesting that “political will is a close cousin” as well. “If you’ve got your community and everybody in it lined up, you’ll get a lot of stuff done. But lack of alignment is a hindrance.” And that speaks to the need for a shared vision a community can rally around.

Just as Ruther described a more recent focus on the “community” part of resort community, so did Lindstrom. “You can’t have a community if you don’t have residents, and you can’t have residents if you don’t have a housing stock for them to live in,” he said. “And it’s as simple as that.”

Ruther and Lindstrom both discussed finding workable partnerships with private developers and opportunities to align their work with resident-worker deed program.

When I described Vail InDEED to local real-estate developer Ian Rasch, he seemed to like it immediately. He’s told me that he prefers having full-time residents in his buildings, despite his market studies that suggest his upscale apartments will appeal to older part-time residents who want to live downtown.

And while it was just an overview of Vail’s program, he seemed quite interested. And suggested that he’d consider deed-restricting some of his new apartments at no cost to the town.

“From my perspective, there’d be no cost to that,” Rasch told me last month. “As long as [a tenant] meets the same requirements, goes through the same application process, and financially they can sustain the rent. But I don’t see any need to attach an incentive to it.”

That presents at least some opportunity for Great Barrington, given that normally a resident-worker deed restriction comes at a cost. Some combination of affordable units underwritten by Community Preservation Act and other funds, and some number of resident-worker deed restrictions on his new rental units would provide both affordable units and some higher-end workforce housing. At minimum, there’s a conversation to start.

In Nantucket, a similar approach

At roughly the same time George Ruther and Steve Lindstrom were scheming up Vail InDEED, something very similar was brewing a couple of hundred miles east of Great Barrington in a popular tourist destination with a population of around 14,000 that more than triples in summer: the island community of Nantucket. And that’s when Tucker Holland, a former executive with a Vermont-based winter-sports-equipment manufacturer, returned with his family to the island—where he had spent a portion of his childhood—to live and work full-time.

Almost immediately, he became involved with local nonprofits working to address a longstanding housing crisis that made affordable housing nearly impossible for the seasonal and year-round workforce to find. Increasing numbers of workers were commuting daily by ferry or air from towns on Cape Cod.

Of course, housing has always been expensive on Nantucket: Pre-pandemic, the median home price was around $1.5 million. But today it’s approaching $3 million. That’s made creativity in addressing the challenge urgent and a substantial investment mandatory.

At first, Holland, whose family has had an antiques and interior-design business on the island for 40 years, and who received his MBA from the University of Michigan, spent a year as a consultant paid by one of those nonprofits, ReMain Nantucket. It was established and is led by Wendy Schmidt, wife of former Google CEO Eric Schmidt. Holland was charged with examining the various efforts underway on housing. A bit more than a year later, he was hired by the local government where he now serves as housing director.

“You can’t live here and not either be directly affected or know someone who’s directly affected by the housing crisis,” Holland told me this week. “And that’s how we refer to it. And so what we did was build awareness.”

To start that process, Holland helped create a website and short video called Ripple Effect to show how urgent it was to house its workforce—and what it would mean for islanders if it couldn’t solve the problem. “Unless you’re helping people understand how it affects them, even if they’re in secure housing, you’re not going to get their attention,” he said. The video sought to personify the crisis. “Imagine a Nantucket where you don’t have a police force. It isn’t such a crazy thing if we don’t address this issue,” he said.

While the video is hard-hitting—at one point, it shows a row of Nantucket police offers vanishing into the ether—it also has lighter moments. That’s thanks to narrator Brian Glowacki, a professional comedian from Nantucket. “His message was, ‘Hey, this issue is no laughing matter. We know how to solve problems, and let’s solve this,’” Holland said. As a Nantucket resident, Holland told me that he also helped to recruit and elect Select Board candidates who supported plans for a bolder housing agenda.

In what may sound familiar to those in Great Barrington, the community already had a variety of housing efforts underway. But different groups were largely acting independently. There was a local housing authority, nonprofit organizations like Habitat for Humanity, its town-based Community Preservation Committee (CPC) and Affordable Housing Trust (AHT), and a group to administer a zoning-related program that encouraged new construction on small lots and deed-restricted that inventory for local workers in a way like Vail InDEED. But all these groups were not working in an organized way that advanced significant progress.

“This position [of housing director] was designed to look at the big picture and how can a multi-pronged approach to solving the issue come together,” he said, describing the impetus for a town employee focused exclusively on housing. Holland works closely with the AHT, which the town determined was the best place to focus all financing of various housing efforts. “We established the AHT as the central funding point for all housing-related activity,” he said. “So rather than have housing-related organizations going [separately] to the AHT and CPC, all funding efforts are coordinated under the AHT, which then goes to the CPC each year with a single request.”

Holland’s role as an organizer and catalyst means he’s constantly reaching out and coordinating with all the island’s housing-related organizations. “We go out proactively and say, ‘What are your plans for this year? And how much are you going to need to affect those plans?’” he said. “And then that’s all rolled up into what we go to the local CPC for.”

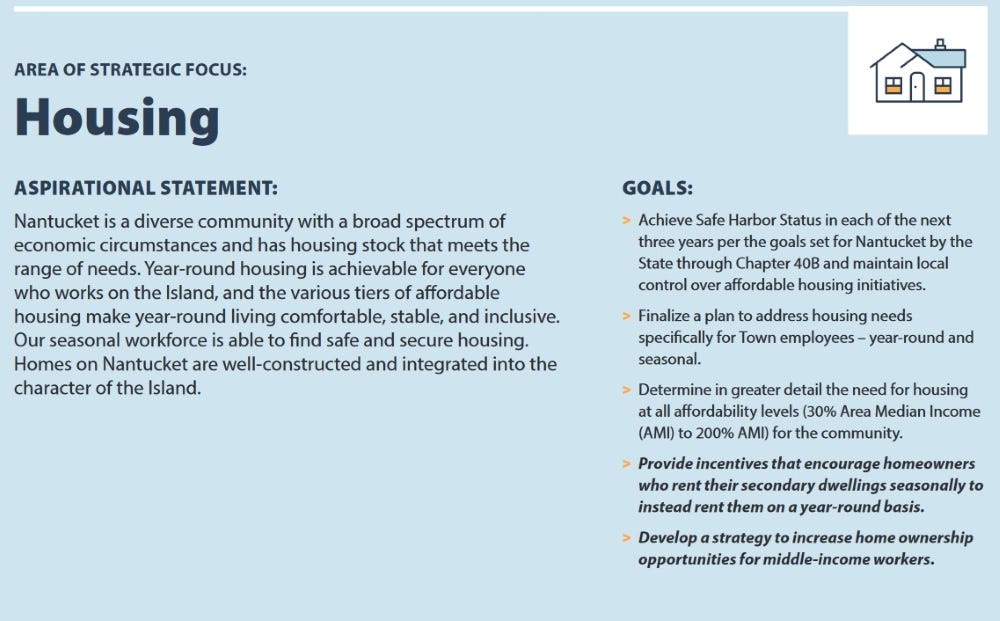

His position originally reported to the town planner but he has since been made a direct report to the town manager. The Select Board has made housing a priority and every year issues a specific list of goals within Nantucket’s concise strategic plan—rooted in things like Nantucket’s master plan and housing-production plan but which presents focused and actionable goals.

“In a place like Nantucket where you have hundreds of people looking for housing, creating [only] a handful of units a year we [were] never going to catch up,” Holland said. “We needed to have a bolder, more coordinated, more substantial approach to addressing really what is an existential issue for the year-round community.”

He told me that he spent his first couple of years in the job building political and community support for substantial action, which included the “Ripple Effect” video. When he began, the AHT had a meager $250,000 in its coffers. In just the few years since, he’s spearheaded efforts that have, to date, secured a total of $67 million in direct funding and bonded authorizations to pump into a variety of housing efforts. And even that’s not enough, he told me, suggesting that Nantucket’s housing challenge is on the order of “hundreds of millions” of dollars.

The work so far has helped increase the island’s percentage of affordable homes from two to six percent, toward the state’s mandated minimum of 10 percent, which is required under what’s known as “Chapter 40b.” Communities below that level can face development that can bypass zoning requirements, so it’s vital to be on a “safe harbor” path that shows 10 percent is within reach. Holland has also been able to encourage projects by nonprofits and private developers to focus on housing for full-time residents.

Importantly, having a housing director has helped to focus all the work on the island. “It was all great work,” Holland said of the committees and nonprofits working on housing. “But I’m not sure the left hand and right hand were talking together as much as they do now, let’s put it that way.”

In something reminiscent of Ruther’s approach in Vail, Holland, fresh in his job as housing director, went to the Select Board late in its budget process but argued they had to get started immediately. At the time, all he had to work with was the $250,000 held by the AHT. “Well, that’s not going to get us very far in a place where the median home price was $1.5 million,” he said. So he went to the board and requested a million dollars for the AHT and told the board it would send a strong signal that the community was serious about ramping up efforts to address the crisis.

Immediately, he said, he had to convince a skeptical Select Board chair. “I said, ‘Well, it’s awfully hard to pull a rabbit out of a hat without even a hat.’” The chair got on board, Holland got the money, and he was off to the races. Last year, Nantucket’s town meeting approved $20 million for housing-related projects. “People here very much understand the issue today and the importance of the community addressing it,” he said.

In the last few years Nantucket has increased the number of subsidized affordable housing units from 121 to 299. But there’s much more to do, including more of a focus on affordable for-purchase homes, Holland said. To help fund its efforts, Nantucket is one of many communities in the Commonwealth waiting for an affirmative vote by the legislature to authorize local authority to institute a real-estate transfer tax of one-half percent. On Nantucket, that would apply to the portion of a property sale above $2 million. The proceeds would all fund housing-related efforts.

That help is needed as demand for affordable housing for full-time Nantucket residents remains high: Holland described 100 new housing units expected to come online soon for which there are already 500 fully qualified applicants.

Since 2002, the island has also had a program, enabled by a Nantucket-related state law, that allows property owners to split their parcel to create additional housing for Nantucket workers earning up to 150 percent of the area median income. So it’s a zoning-based approach that Holland told me is adding five or six homes per year to the inventory of housing for year-round residents.

To help meet Nantucket’s ongoing housing-price challenge, next up is an exploration of plans to create a community land trust. That’s a property-ownership model that separates the speculative value of land from the housing that sits on it. That can help leverage a variety of financial resources to help create housing that remains affordable in perpetuity, by buying the land out from under the homes.

Community land trusts were pioneered in the United States decades ago by Egremont’s Susan Witt and Bob Swann, building on a movement that flowed from Israel’s Jewish National Fund a century ago, through similar efforts in India and then in the American South, where Swann was active in the late 1960s. Here in the Berkshires, the Berkshire Community Land Trust (BCLT) that Witt and Swann founded in 1980 carries on the work, lately with a focus on preserving farmland. (Disclosure: I served on the boards of BCLT and its companion organization, the Community Land Trust of the Southern Berkshires, in 2018-19.)

In our region, a lack of affordable housing for working families is not a new problem, but it’s become substantially worse. Written almost a decade ago, the 2013 Great Barrington master plan notes that “many people who work here have trouble finding an affordable place to live here.”

The solution in tourism-based, second-home-heavy places like Vail and Nantucket may make sense here: Preserve housing, and build a market, exclusively for resident workers. Create housing inventory that, when it comes up for sale, won’t be scooped up in minutes or hours by part-time residents who can afford to make all-cash, no-contingencies offers that, while terrific for the bank accounts of real-estate agents, have proven to exacerbate the housing crisis.

In Great Barrington, a host of boards and committees, nonprofits like Construct and the Community Development Corporation, and private developers like Rasch are all part of the mix. But as Rasch, Select Board member Leigh Davis, and many others with whom I discussed housing issues this summer and fall point out, a lot of that work goes on in silos without enough collaborative planning or action.

Indeed, Abrams and Planning Board member Pedro Pachano, a local architect, had spent months in their “It’s Not That Simple” series on WSBS Radio and in The Edge detailing the housing challenge, but only lightly addressing proposals for action and never turning them into a concrete, actionable proposal.

At that February meeting, Abrahams said his list of ideas “had mostly come from Chris’s head,” referring to Chris Rembold, the assistant town manager and director of planning and community development. The board then directed the list of Chris Rembold’s thoughts on housing back to the one-person planning department, a.k.a. Chris Rembold, for further study.

Then, this summer, the Planning Board spent some time drafting its own one-and-a-quarter-page letter of housing ideas, also with Rembold’s help (he’s the board’s staff liaison) and sent it to the Select Board. Fully two months later, on October 3, the Select Board discussed the letter and referred it for additional research and investigation to … Chris Rembold, presumably to keep with his growing pile of letters filled with his own ideas.

A couple of hours before the Select Board’s October 3 meeting, I called Chairman Steve Bannon to ask him, for this series, if the town needed to better organize its efforts on housing, and whether it needs an action plan beyond referring Rembold’s ideas back to Rembold.

He readily agreed. Bannon told me that he’d had recent discussions about that very question and that he planned to bring it to the board that evening. “There’s four committees and subcommittees all talking about [housing], but nothing cohesive,” he told me. “I think we need to start to try to bring it together.”

That night, Bannon brought it up and asked the board to authorize the creation of an “executive summary” of what ideas various town boards were considering on housing. “How can we move this forward instead of just talking about some great ideas, how we can actually implement these, when they are most badly needed, which is now,” he asked his colleagues.

The board agreed. Who would create the executive summary? Chris Rembold.

Bannon continued: “My assumption is that when Chris comes back to us, he won’t have ideas that require us to win the lottery to implement because we’re just going to be spinning our wheels again,” Bannon said. It was a reminder that Bannon’s steady, level-headed ability to manage the Select Board’s processes, and wrangle its members to move ideas forward and find common ground, is valuable and perhaps underappreciated. But his caution, particularly around nascent ideas that may have significant budget impact but are worth exploring, may be a weakness.

During the discussion that followed, Bannon, Davis, and Abrahams all chimed in about the need for better cross-government organization and action. Abrahams, importantly, focused on the need for specific goals and metrics. Davis said her housing subcommittee has been assembling a spreadsheet of housing ideas with rankings for how much work each idea might take, in service of what she told me last month will, she hopes, eventually lead to an action plan. She told the Select Board that night that between housing subcommittee meetings, she’s been working on the spreadsheet with … Chris Rembold.

Ultimately, the subcommittee’s final list will be brought forward to the full Select and Planning Boards in the coming months. And from there? You could do worse than push all your chips to the “Referred to Chris Rembold” spot on the roulette wheel of Great Barrington housing policy.

An irony, if any, is that Rembold is enormously well versed on all these issues. But as assistant town manager and director of planning and community development, he is tasked with many other responsibilities. And he’s a planner by nature, not an executive or town decision-maker. He has the understated temperament of many in the profession, not least because they seem preternaturally inclined to revel out in the weeds of zoning bylaws that may have policy sections nested four deep, like “7.7.1.2” (which requires fast-food restaurant drive-throughs in Great Barrington to be no closer to each other than 1,500 feet). He’s worked for the town since 2009, has experience and broad knowledge, and also what close observers of town government have come to appreciate as a sly, subtle wit.

Rembold is aware of the Planning Department’s limited resources. He told me in September that he’s not sure time spent developing a housing action plan is needed, pointing to existing guidance in the 2013 master plan and a 2020 housing-needs assessment. (And perhaps because his task list already runs to 800 pages.) “Obviously you need staff to write the things, and in Great Barrington, I mean, that’s me,” he said with a laugh. “That’s not positive or negative,” he added quickly, comparing Great Barrington favorably to other towns that don’t have capacity or the resources to hire staff or consultants.

He seems comfortable with the current process. “We have the recent data, we have good overall policy, and we have a variety of boards and committees working on housing issues,” he said. “So it may be that we just need to continue creating housing and preserving housing rather than [creating] another plan.”

He said he’s open to examining a program like Vail InDEED, which would align with his goal of preserving housing and slowing the pace of price increases for resident-worker housing. But, again, he highlighted the question of resources. “It’s something that needs a lot more cash put into the program, a lot more staff. So again, it’s going to depend on the local context and just how much the town wants to dedicate to these programs.”

On the question of creating a housing director position in Great Barrington, Rembold said he hadn’t considered it. And, conscious of the live wire that is Great Barrington’s tax rate, responded cautiously. “There’s a sweet spot between the issues and challenges facing a community versus the resources in terms of money and time and appetite of voters to adopt those and meet those challenges,” he said. “And sometime putting additional staff to the problem just doesn’t meet the challenge, because at the end of the day, the voters have to approve it. If you’re just burning money on staff without an agreed-upon policy agenda, then it’s not really useful. I think in Great Barrington we have the policy directive,” he said, again noting prior plans and reports. But he acknowledged that, at minimum, “There are issues we could study more in depth with additional resources.”

Town Manager Mark Pruhenski told me recently that while there’s no specific plan to expand the planning department, he said it may be considered in the FY2024 budget process.

In the end, of course, it’s not Rembold’s job to lead or decide. Whether the Select Board will empower him or hire a housing director to join the planning department, and marry that role to a Vail- or Nantucket-like mandate and action plan that frames a request for substantial funds, all remains to be seen. At minimum, Great Barrington could join with other south county towns to create and fund a regional housing director, much like it did this year for human resources.

Abrahams, for his part, seemed enthusiastic about the idea of a housing director when I asked him about it last spring during the STR debate. Though he’s told me several times this year that he’s skeptical town voters will allocate substantial funds for housing. “If you put a million dollars on the warrant for housing, I’m not sure it would pass,” he said.

Davis, who, despite her focus on the urgent housing crisis, seems to prefer a more go-it-alone approach, told me recently that when it gets further into its work, the joint housing subcommittee she chairs may consider hiring a consultant. Earlier this year, when I asked her if Great Barrington should hire a housing director, she said she believed those funds could be better spent.

In contrast, Pedro Pachano, the local architect and Planning Board member who has helped advance zoning changes that encourage new housing development, is all in for an expanded planning department and housing director position. In a wide-ranging conversation this week about recent zoning changes that enable more development of housing on State Road, and next steps on housing policy, he suggested there’s no time to lose.

While he discounted the need for a concise action plan, Pachano pointed to the need for more leadership. “It’s up to the people in positions of power to actually implement those things,” he said, clearly speaking of the Select Board. “And I think if we had a director of housing, that’s not just Chris [Rembold]’s title, but somebody who’s focused on housing and economic development in town, they would be charged with figuring out ways to do it.”

He suggested Great Barrington needs a minimum of three people in “an empowered office” to focus on housing. “Chris and two people I think would be great,” he said. Without that commitment of resources, Pachano suggested, “There’s really no means to accomplish whatever goals you set for yourself.”

Still, zoning changes and staffing may only get the town so far. Also needed is political will and backbone to execute on opportunities. And also a willingness to confront the persistent NIMBY challenge that continues to stand in the way, derailing Rasch’s 45-unit Manville Place project and significantly reducing the size of a promising new affordable-housing development on North Plain Road.

Jonathan Hankin, who has served on the Planning Board for a couple of decades and is not shy about sharing his take on things, has been highly critical of early plans for that North Plain Road project, on land acquired by the town and being developed into affordable for-sale houses by Central Berkshire Habitat for Humanity.

Based on the parcel’s location and zoning, he says there could be up to 60 units of housing. “But [the AHT] thought the neighbors were more important than affordable housing. So that’s where we are,” he told me, referring to an early, and loud, outcry from neighbors and the project’s current plan for only 20 homes.

“There’s nothing to prevent [Habitat for Humanity] from coming in with an initial plan and then adding density later,” he said, suggesting it would quickly show abutters they have nothing to fear. “When the neighbors see that, [they’d see] it’s not really a problem. Except that the way they’ve laid it out that precludes future development.”

Overall, he sees this as a missed opportunity, given the dearth of good building lots. “What’s interesting is that this is a chance to build a neighborhood where everyone owns their own home. You know, which is huge. We don’t have that anymore,” he told me. He specifically worked to advance this project with the Affordable Housing Trust because it was a homeownership opportunity, he said, and one that could potentially have been up to five-dozen units. “I’m fed up with all these huge projects that are 100 percent rentals. So I think it’d be nice to have and this is a chance to be really a model program for the town and for the state. And they’re dropping the ball.”

A community planning process

When I talked to Rasch this fall about the need for more zoning changes, a shared community vision, and an action plan, he readily agreed. “These are complex discussions and issues that have to get resolved creatively. And at least it seems to me, there is an opportunity to do that. But everybody has to engage.”

He called for “an intentional strategic vision” to guide housing efforts, and said he supports the idea of public meetings, perhaps with a facilitator, to hear from the community. “We should run a real process and publicize it and invite the public in—no one’s excluded—and have not just representatives from Construct, but also representatives that live in their housing, and representatives that live in [Alander’s] housing and make it a wide enough discussion.” He also suggested engaging Volunteers in Medicine, where he serves on the board, to represent the housing challenges of unauthorized immigrants who live and work in our communities.

Rasch framed an imagined process around some key questions: “What does Great Barrington want? What do we all want? How can we each play our part? How do we work together?” he asked. “It’s a messy process. And that’s why I think it’s mostly avoided. Because it’s just too complicated.”

At other times, though, Rasch suggested the opposite, particularly on funding affordable units in his upscale downtown projects. He told me a few times that’s not complicated at all, and that the town should absolutely underwrite some affordable units in his buildings.

Indeed, earlier this week, Rasch initiated applications with the CPC for $500,000 toward eight more-affordable units, at still-undetermined income limits, out of the total of 35 upscale apartments he’s building at 343 Main Street and the Mahaiwe Block. He also requested $150,000 for historic-preservation work at the Mahaiwe Block.

Combined with $250,000 awarded earlier this year to Alander for external historic-restoration work at 343 Main Street—which the CPC voted this week not to rescind because of the building’s change in use—his company has requested a total of $900,000 from the town over the last year. Yet without a clear housing plan that delivers on a shared community vision, and that details specific goals, it’s unclear how the CPC, or town voters, can weigh Rasch’s funding request against any alternatives.

To that missing vision, Rasch is correct that it’s complicated to create a successful dialogue that addresses the broad scope of the housing challenge. To his credit, he appears genuinely interested in advancing that conversation. He told me that he’d donate half the cost of a facilitated public process or “charrette,” to use the not-very-popular term for a guided brainstorm, to try to wrangle all the people and organizations and ideas in service of a shared vision. (To be fair, we didn’t talk about a budget, so he shouldn’t be held to paying for 50 percent of a million-dollar planning process.) All of that said, he strikes me as quite confident that his vision will prevail.

Leaning on Great Barrington

Paying close attention to Great Barrington’s struggle with affordable and available housing for its workforce in recent years has highlighted something little discussed: What should other South County communities be doing to help?

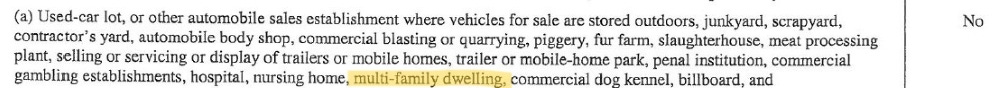

The small town of Alford, where I’ve lived since 2008, approved an updated zoning bylaw in 2002 that seeks to maintain a community of single-family homes on large parcels of land. The basic dimensional requirements for a single-family home are two acres of land and at least 250 feet of road frontage. The bylaw only permits a two-family home, the kind that commonly provides more affordable housing, if it’s on twice as much land with twice the road frontage. And it still requires a special permit from the Planning Board.

An Alford property owner can add another house on what’s called a “rear lot,” as long as the rear lot itself contains at least four acres and the second building comports with a list of other requirements. So to add an additional house for year-round rental housing would require a parcel owner to have a total of six acres.

Other options to add housing include building an accessory apartment, like one that might be above a garage. That’s also only allowed with a special permit, and only after meeting a long list of conditions that call for “avoid[ing] the appearance of a two-family dwelling,” “adequate visual screening and protection of adjacent properties…,” and that it will “not be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood than would a one-family dwelling.” Curiously, it must also have its entrance only on the side or back. Finally, the property owner must occupy either the main house or the accessory apartment, preventing the creation of two units of rental housing.

And while it would be nice to imagine it’s presented this way simply as a matter of convenience, the bylaw’s table of uses includes a list of what is not permitted at all in Alford—and for which there is no option for a special permit from any board. A sizeable list lumps together unwanted and impermissible uses like junkyard, scrapyard, piggery, fur farm, slaughterhouse, meat processing plant, penal institution, and commercial gaming establishment. The list also includes “multi-family dwelling.”

The town’s small Planning Board, which is responsible for recommending any changes to the zoning bylaw to town meeting, has been working this year on the many complexities of a short-term rental bylaw to enable some limited STR rentals, for some number of days per year, as well as include basic health and life-safety requirements. The goal, according to board member Shirley Mueller, is to find the right balance between residents earning extra money they may need to afford to stay here while also preserving housing for year-round residents. At present, Alford does not permit any property rentals for less than one month.

Mueller told me in a phone call this week that it’s been quite a lot of work for a small volunteer board. (You’d be hard pressed to find anyone more engaged in town and volunteer activities than Mueller.) And it comes on the heels of several years of work the board did to craft bylaws related to solar installations and cannabis, all without the help of town staff or hired consultants.

To my question about zoning restrictions related to multi-family dwellings, she suggested it could certainly come up in the context of ongoing Planning Board conversations about addressing housing needs. But the board is already stretched thin with its current task, she said. “It is definitely something we should address,” she told me. “But how we don’t know yet. And we certainly are open to suggestions from people.”

Larry Gadd, the current Alford Planning Board chair who’s served on the board for more than a decade, gave me an expert over-the-phone tour of options for property owners who might want to add a house on a rear lot or build a development road to increase frontage on a larger lot to enable construction of additional homes. They would still need to meet the usual dimensional and other existing zoning requirements, as well as special permits as required.

As for multi-family housing, Gadd didn’t express a specific opinion but agreed it’s something to consider, given the need for more affordable housing in the region. “That certainly should be brought up, and we should discuss it,” he said. Multi-family housing hasn’t come up previously at the board, he said. But Gadd understands the housing crunch: He told me that he sees the same challenges around affordable and workforce housing unfolding on Martha’s Vineyard, where he also has a home.

Given what we know about how our regional economy works, and the centrality of Great Barrington to surrounding towns, it’s worth considering this: If Great Barrington and all it provides didn’t exist, neither would Alford. At least not in Alford’s current form, which has no infrastructure needs for a business district, extraordinarily low taxes, and enormous swaths of open space and undeveloped land. All of which is a delight and appropriate to have in the regional mix. And no doubt Alford’s natural attractions and beautiful roads for biking help bring tourists and others to the region.

Still, with little infrastructure to support, and many valuable homes and properties, our taxes remain low: Currently $5 per $1,000 of value compared to Great Barrington’s $14.86. And no doubt our low tax rate is, by extension, underwritten by the higher taxes paid by Great Barrington property owners to support the town’s infrastructure and amenities that make living in Alford possible, from grocery stores to restaurants to pharmacies to countless necessities and pleasures. That low tax rate also inflates our property values, which is, again, made possible by higher taxes and the business ventures and amenities provided by Great Barrington (and other larger towns).

This is simply to point out that we’re all in it together. And as Pachano put it, the resident worker housing crisis is creating a slow-motion failure of our local economy. Or if not yet at the point of outright failure, we’re approaching the outer edge of an event horizon past which recovery becomes more difficult. And that would certainly affect the quality of life in Alford.

Alford could easily accommodate some modest multi-unit housing amidst its vast open space, even with a limit of two or four units per lot. Imagine an old Victorian home converted to a few apartments and still looking like a single home. Indeed, it’s no secret that many homes in Alford are far larger than what even a four- or six-unit dwelling might be, in terms of what the zoning bylaw refers to as “the size and scale” of a single-family home. That suggests the town can accommodate these more affordable multi-family units in similar-sized structures that would still be “appropriate to the neighborhood,” as the zoning bylaw currently describes various requirements.

Whether Alford and other nearby towns take up these housing-production-focused changes may depend, once again, on both an awareness of scope and impact of the problem along with willingness to shift from NIMBY to YIMBY—“yes in my backyard,” the phrase increasingly used by housing advocates nationwide. If past is prologue, all evidence points to a continuing fight of wealth and privilege against commonwealth and community, both here in the Berkshires and nationally.

Fortunately, there are at least small signs that the tide is turning across the country. Earlier this year, the wealthy Silicon Valley enclave of Woodside tried to derail local implementation of California’s Senate Bill 9, an important new state law that allows homeowners in residential districts to split their lots and build a duplex on each one, creating potentially a total of four housing units. It’s part of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s aggressive effort to address that state’s critical need for affordable housing.

In response, the town, with a little more than 5,000 residents, an annual median income north of a quarter million dollars, and popular with tech entrepreneurs, passed an ordinance declaring the entire town to be a “protected mountain lion habitat.” Ridicule followed. And it didn’t take long for the state’s attorney general to weigh in and make clear that he wouldn’t stand for it.

So the town soon rescinded the habitat designation and began accepting applications for construction under SB9. In the New York Times’ coverage of the story, a wildlife biologist said, with delicious understatement, “There aren’t any studies that say converting a single-family housing unit into a duplex will have an effect on mountain lions.”

As examined in the first installment of this series, Rasch’s focus on downtown redevelopment avoids the NIMBY challenge he ran into with his failed Manville Street project. Instead, purchasing and “repositioning” downtown buildings with high-end apartments is a more straightforward way to offer residential housing, profitable over the long term, in an increasingly affluent community.

Living downtown no longer

A few times in our conversations, Rasch pointed to a Mahaiwe Block resident we both know. He’s a writer who has been a resident of the area for nearly half a century. He’s now been displaced, and recently completed a laborious, weeks-long relocation to Housatonic, climbing up and down the stairs to his third floor Mahaiwe Block apartment with bags of his things, loading his car, and shuttling them to his new apartment. (Rasch is providing some assistance for the new rental apartment.)

“When trying to create a downtown urban core that is sustainable and economically resilient, we have to solve this mixed-income problem,” Rasch said, in various ways, during our conversations. “The next level of discussion is the intentionality around how to integrate those people into the town. How do they have garden space? How do they live alongside people like you and me? Not so [they’re] all segregated out?” he said, again suggesting that affordable-housing developments on the outskirts of town are not ideal.

“In the limited way that I can, I’m going to solve that because it’s an ethical thing for me,” he said. Referring to our mutual friend, he said, “He represents what this town should be, and has been, for the last 30 or 40 years. And if you take that away, I’d feel miserable.”

Our friend told me recently that he was happy to be leaving downtown and moving to Housatonic. He pointed to the pace of gentrification in Great Barrington, an increase in noise and traffic near the Mahaiwe Block, and said he had no desire to continue to live downtown.

Breathing rarefied air

At one point in a conversation in early September, when discussing the challenges experienced by a local workforce trying to afford housing, Rasch described what he felt had awakened people to the scale of the problem. “The sort of moment of truth for everyone [was] when they can’t get their landscapers and they can’t get their [house] cleaners in, like that’s really real. And it’s become more real with COVID,” he said.

It was interesting to hear Rasch frame it that way. Quite a lot of Alander’s work in recent years has been building what he described to me as “second, third, fourth, and fifth homes” for people “unconstrained by the [financial] markets,” where discussions about which $250,000 French oven to install were, he confessed, challenging for him. It’s rarefied air, for sure. And spending time breathing it can have an impact.

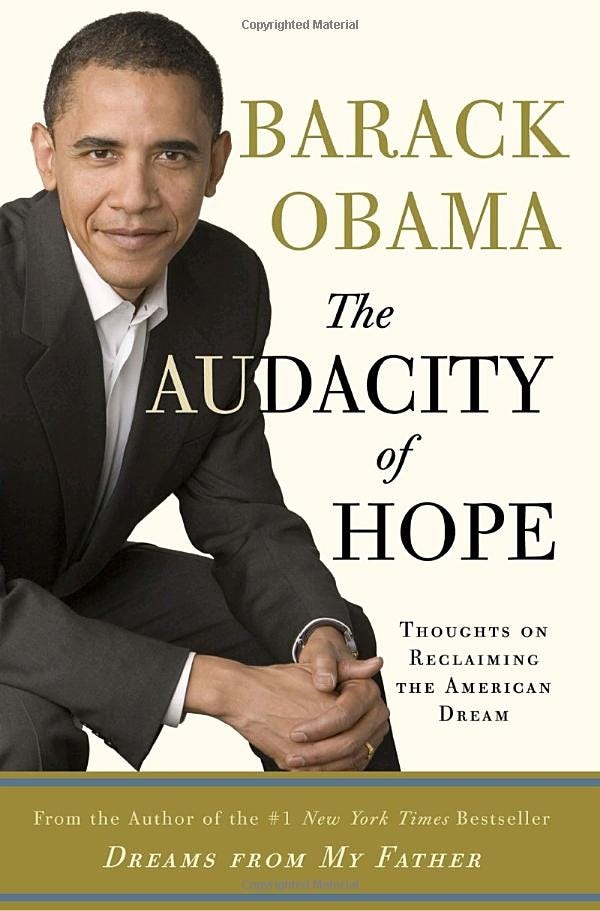

Former President Barack Obama wrote about that impact in “The Audacity of Hope,” his 2006 campaign memoir that described his years in the Senate. It’s safe to call Obama a traditional progressive, at least in outlook and values if not entirely in the policy prescriptions he championed. His aspirational rhetoric—a way of communicating that Rasch has in his toolbox as well—fueled his rise to the presidency. Yet those soaring speeches also misrepresented how transformational his actual policies would be, constrained as he surely knew they would be by realpolitik, racism, and the broken political system in which he was operating. And, in the end, his desire to win re-election.

In his book, Obama devotes several pages to how years of fundraising among wealthy donors had “narrow[ed] the scope of [his] interactions” and, despite his efforts to resist it, left him with a day-to-day schedule that “dictates that you move in a different orbit” from the greater mass of people. And he worried that it was changing him.

“Increasingly I found myself spending time with people of means—law firm partners and investment bankers, hedge fund managers and venture capitalists,” Obama wrote. “As a rule, they were smart, interesting people, knowledgeable about public policy, liberal in their politics, expecting nothing more than a hearing of their opinions in exchange for their checks.”

But Obama couldn’t avoid noticing what he described as “the perspectives of their class,” which he said meant they often had limited sensitivity to the struggles of the broader public and “were not particularly sympathetic to those whose lives were upended by the movements of global capital.” And he said that over just his few years in the Senate—he served from 2005 until his first presidential inauguration in 2009—he found himself disconnected.

“Still, I know that as a consequence of my fund-raising I became more like the wealthy donors I met, in the very particular sense that I spent more and more of my time above the fray, outside the world of immediate hunger, disappointment, fear, irrationality, and frequent hardship of the other 99 percent of the population that is, the people that I’d entered public life to serve.”

The problems of ordinary people,” he wrote, “become a distant echo rather than a palpable reality, abstractions to be managed rather than battles to be fought.”

Another time, while discussing his Prospect Lake campground project, Rasch described his paddleboard outings along the shoreline of the campground and near the beaches where people have frolicked and played and swam and vacationed for the better part of 100 years. “And then I noticed two things,” he said. “One, where people were not involved, where, like, nature was just allowed to do its own thing, you had these natural rock outcroppings and a riparian edge that sort of self-sustains itself. In that, you know, where there wasn’t, you know, trampling and there wasn’t drainage of water going into the lake. And then there was, very prominently located, the main beach where [former owner Jim Palmatier] would dump a couple of hundred tons of sand every year that would just wash in.”

In early plans he shared with me and the Egremont Conservation Commission for his new park model RV resort, which will reduce the number of guest sites from 125 to 40, access to the water will also be limited. There will be no beaches or direct entry to the water from the shoreline. Instead, there will be a few piers extending out into the water for those who want to swim.

The future of downtown

If there were moments in our conversations when Rasch became slightly defensive, it was in response to any suggestion that Alander was hurting, rather than helping, to address the housing challenge for working people in the area. He told me repeatedly that he was adding new, desperately needed housing, including at least some affordable units—at a Community Preservation Commission meeting this week, he said there would be eight between 343 Main Street and the Mahaiwe Block, a mixture of studios, one- and two-bedroom units, and including a large ADA-compliant two-bedroom apartment at 343 Main.

In the document he sent me in advance of our first meeting that described his company, biography, and thinking, he wrote that “Alander is addressing this with the addition of 35 new housing units in downtown Great Barrington … but many more rental units are needed and Alander cannot act alone.”

Setting aside the incorrect notion that no one else is working to address the region’s need for more housing, it’s also inaccurate to claim that Alander is adding 35 units. With its two downtown projects, his company is adding 23 new housing units; there had long been 12 apartments on the top floor of the Mahaiwe Block where working people lived, until quite recently, at affordable rents. Other downtown buildings also house resident workers—admittedly in apartments with fewer amenities and without high-end finishes—also at affordable rents.

In one of our first conversations, Rasch talked about why it’s important for him to have a vision that can look out decades, given both the expected life of his renovated downtown buildings and considering economic development more generally. And also how much he likes the set of challenges he’s set for himself.

“I’m very comfortable working with these old buildings, I love it,” he told me in September, “because they’re part of the historic fabric of this community. So I will continue to try to find them and, you know, reimagine them and work with whoever’s interested in working with us, and I hope other people will do the same,” he said.

Given his plan to “reposition” these buildings as luxury apartments, with perhaps 20 percent of them reserved at lower rents, I asked him how he’d react to someone who didn’t share his vision or care for his plans. He seemed not to think that even remotely possible.

“Well, how could you disagree with creating housing opportunities for everybody on the entire income spectrum in downtown? So you have affluent second homeowners, young professionals working at Fairview, architects, which we have already living in [47 Railroad],” he said. “And then you have, you know, people who have lived here for years, like [the Mahaiwe Block writer] and they should have a door that they can open and that’s their space, and that they are, you know, they are a representative part of the community. How can you argue with that? It’s about creating what these towns probably used to be like, much more than they are today—an integrated, mixed income community where there’s accommodation for everybody.”

It was a fascinating response, not least because it again showed Rasch’s holistic vision for his version of downtown. But it also highlighted one of his blind spots: He overlooked that Great Barrington’s downtown is now, and has usually been, a mixed-income community, but one with fewer affluent residents.

Other than 47 Railroad, which Rasch and Sam Nickerson built in 2018 to offer luxury downtown apartments that now command rents of $2,500 to $3,500, the rest of downtown continues to provide affordable apartments for local workers and others. Rasch’s pursuit of “mixed income,” it now seems, means adding high-end housing that doesn’t currently exist. So his plans would flip the downtown script: If downtown is redeveloped as he’s described, eighty percent of those living there in a decade or so will be affluent and able to afford his new apartments. If he delivers on his promise to find a way to offer some lower-rent units, 20 percent will be lower- and middle-income.

Rasch told me that on a range of issues, from the design of downtown buildings to the need for affordable units, developers like him should have their “feet held to the fire.” He seems willing to engage, confident he’ll carry the day even if there’s some opposition. “This is not about me. It’s working as a conduit to solve a couple little things that I can do in my tiny little community,” he said. “And it’s not whether neighbors or abutters or people who clap or yell or jeer or whatever it is. That’s sort of meaningless to me. Because I know this is a real issue that I’m trying to solve in a very limited way.”

He’s certainly proven he has the focus, stamina, skills, and financial resources to power ahead, no matter the objections or the obstacles. In fact, one early fall morning, as we sat beneath a warm sun outside his 47 Railroad complex, after more than an hour of conversation I asked him about that very issue.

“It’s interesting,” he began after a noticeable pause. “I’ve been doing this for 20 years. I have never done a project where someone came out clapping and said, ‘Oh, this is spectacular.’ There’s always a lot of pushback, always a lot of criticism, always lawsuits, everything. But to me it’s about having a vision, ten, twenty, thirty years ahead, and trying to implement a small piece of that. And I can say there hasn’t been an instance yet where after the fact, people came and said, ‘Oh my God, this is a fucking disaster.’ It’s like, you have to put it out there, you have to move through all of that. And at the end, people see the final product and say, ‘Okay, that kind of makes sense.’ Right?”

That ability to push through criticism and opposition is invaluable for a developer. Essential, in fact, no matter how broadly embraced or despised their projects might be.

Rasch’s soliloquy is reminiscent of something from “Straight Line Crazy,” the new David Hare play currently running at The Shed on Manhattan’s West Side. It’s a show about Robert Moses, the controversial urban planner and longtime municipal official whose personal vision for New York City pushed aside democracy, elected leaders, budgets, poor families, immigrants, and others during the 40 years of mammoth transformation he brought to New York City.

To capture Moses’ view of the those who cried foul, and his opinion of people in general, Hare gave Ralph Fiennes, the actor portraying Moses, these words as a coda: “We must advance their fortunes without having any respect for their opinions … To build a road, it may be that you need to knock down a house. What happens? A lot of screaming and shouting. ‘That has always been there.’ And then when the road is built? ‘Oh my God, how much better this is. How did we ever manage without this road?’ They can’t even remember the house. The people lack imagination. The job of the leader is to provide it.”

(This series first appeared in The Berkshire Edge.)