The century-old Prospect Lake Park campground in Egremont will become an upscale park-model-RV resort. The change was a shock to longtime patrons. The developer says he'll make room for the community.

∎ ∎ ∎

(Read a two-part follow-up to this story: Part one and part two.)

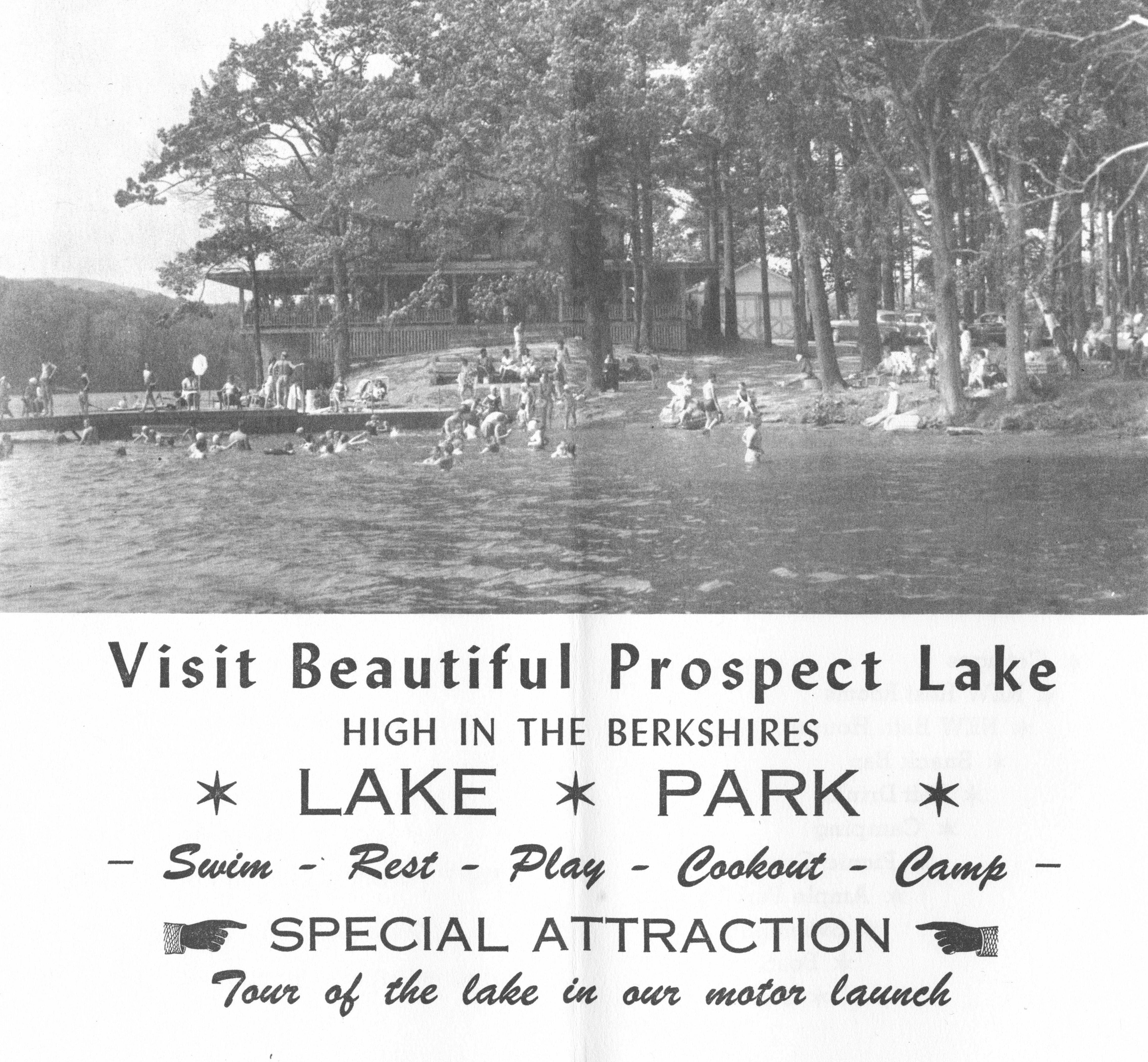

As the author, historian, and Berkshire Edge columnist Gary Leveille described his first visit, as a 12-year-old in the summer of 1964, to Egremont’s Prospect Lake Park in his fascinating, warm, and deeply researched book, “Eye of Shawenon: A Berkshire History of North Egremont, Prospect Lake, and the Green River Valley,” the campground on the eastern side of the lake “was an exciting, adventurous place. It had a towering water slide, raft with diving board, recreation hall with pinball machines and juke box, rowboats to rent, and good fishing! Cute girls, too!”

He describes the park in the 1960s and 70s as “a hugely popular destination for camping families from throughout Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut and beyond.” Filled from late spring into fall with a mix of fun-seeking visitors of all ages in tents, pop-up campers, trailers, and RVs, he tells the story not only of a campground business but of enclaves of “seasonal campers who returned year after year” beginning in the late 1950s.

Leveille’s book spills over with history, remarkable photographs, and reflections from a community of people whose lives were enriched by deep friendships forged over decades of summer adventures at what can fairly be called a simple, unpretentious, and affordable gathering place. It was a campground whose location, long history, traditional amenities, and forest-and-shoreline layout made it more personal and community-oriented than many.

On a now defunct Facebook page set up for a Prospect Lake Park reunion a few years ago, one woman who spent summers there from the mid-1970s into the ‘80s wrote, “I remember the slide, the raft, the rec hall, going tubing and paddle boating. I remember running around the campground from the time we woke up ’til it was time to go to bed. I remember playing ping pong and pool and I remember hanging out playing bingo after dinner,” she recalled.

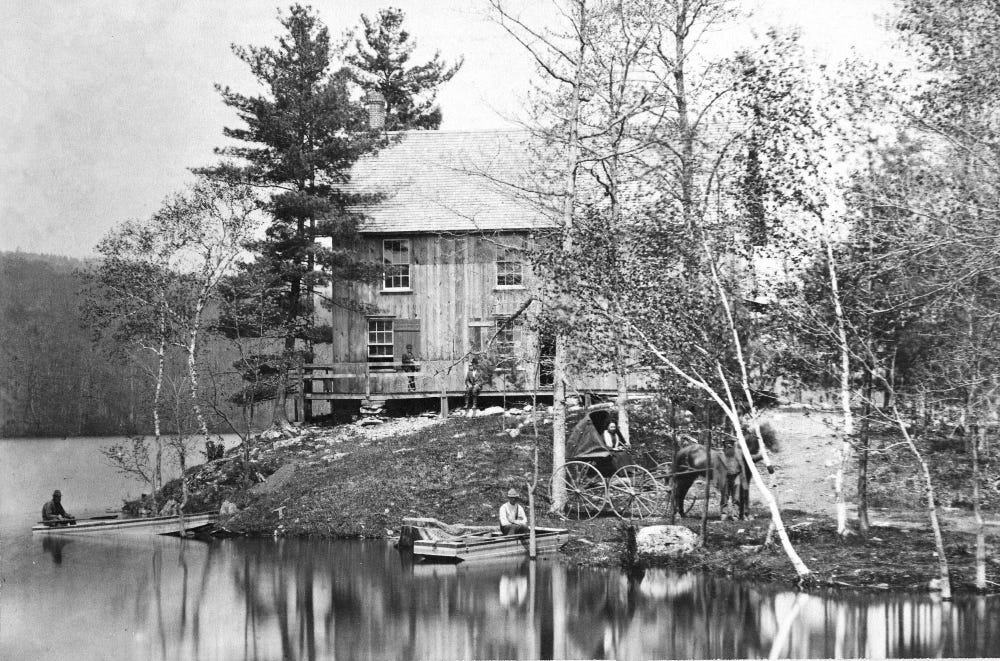

In the decades after the property’s historic but modest Cliff House was built in 1876, nearby Berkshires’ Gilded Age mansions in places like Stockbridge and Lenox—and all that happened in and around them—might as well have been on the other side of the planet from what was growing up along the shoreline of the 56-acre lake.

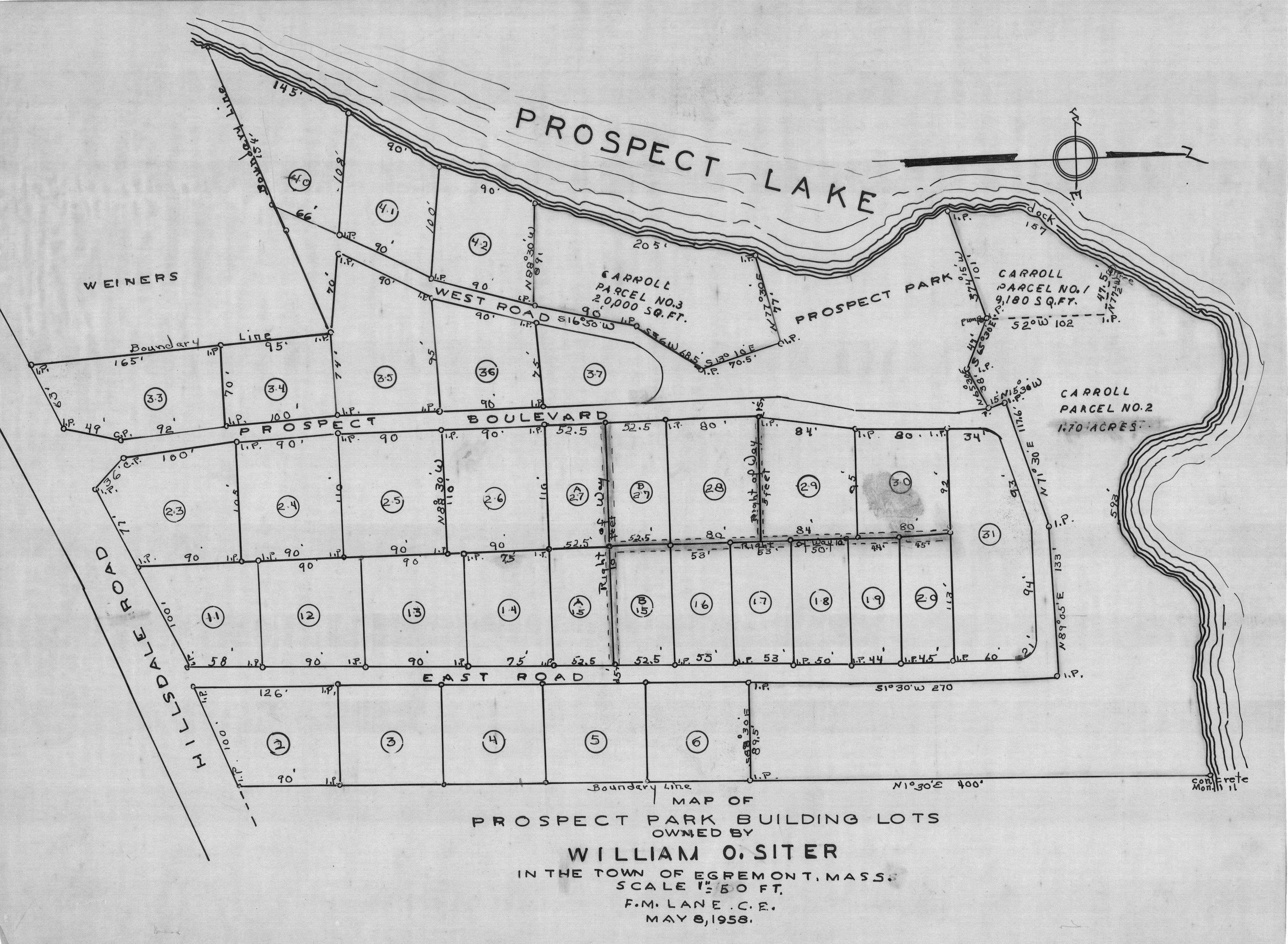

From its first days as a popular Berkshires picnic spot, to its early evolution into Prospect Lake Park with work done by longtime owner Will Siter, who bought the property in 1924, through its many decades of operation until last year, it has remained a place affordable to all. Not fancy, or expensive, or particularly amenity-rich, yet it somehow managed to create fun, recreation, and real community for those who sought it.

“The third annual public opening of Prospect park and lake will be held on Monday, May 30” read a single-paragraph 1927 announcement in The Berkshire County Eagle, describing the park as “a popular picnic resort.” There were similar announcements every May for years, often revealing, in an understated sentence or two, what improvements Siter had made in the off-season. “The boats have been painted,” the Eagle reported without fanfare on May 21, 1930.

Anyone who has been to camp, or played with the same neighborhood kids during long, unplanned summer days, or was fortunate enough to experience that special, and perhaps increasingly rare, coming-together and emotionally resonant bonding among people thrown together by happenstance can easily imagine what Prospect Lake Park was like. And why it meant so much to so many.

Yet it’s the nature of things to change and evolve, shift and reorient.

Real-estate developer Ian Rasch, who lives just a couple of miles away, first became interested in acquiring Prospect Lake Park a few years ago while paddleboarding with his daughter. He marveled at the lake’s beauty and the rock outcroppings along the campground’s 2,000-foot shoreline.

“I just got obsessed with how to restore this property so that it could mimic Jug End, could mimic French Park, but also offer some sort of hospitality experience or park experience for the public and private citizens to engage with Prospect Lake,” he told me in late summer. “At my core, I’m interested in creating beautiful spaces where human beings and nature coexist and interact,” he told me. “It sounds crazy, but that’s what drives me to do what I do, whether it’s in an urban setting or at the Prospect Lake campground.”

After a couple of years of on-and-off-again discussions with the park’s owners, Jim and Kathy Palmatier, his obsession paid off. In January 2022, via an entity called 50 Prospect Lake Road, LLC, Rasch purchased the campground’s two large parcels of land and all its buildings and infrastructure for $2.1 million from the Palmatier’s North Egremont Recreation, Inc., according to records on file with the South Berkshire Registry of Deeds.

He had already purchased an adjacent house and land at 46 Prospect Lake Road a month earlier for $400,000. Until a decade ago, it was home to a former owner of the campground. That property’s deed includes various rights-of-way that have long guaranteed its owner access across the campground to the shoreline and lake. (Rasch told me plans for that property haven’t been determined.)

As reported by The Edge, ten days after the sale, longtime summer residents of the campground received a certified letter from Rasch’s Great Barrington attorney, Peter L. Puciloski, returning their summer 2022 deposits and announcing the park would be closed for the year. It said the new owners planned “significant improvements to the facilities” that required all seasonal residents to remove their camping trailers, many of which were typically left behind during the off-season. During the winter months, they could often be seen from Prospect Lake Road, sometimes protected by tarps and under piles of snow.

Any trailers not relocated by the end of May would be removed, the letter said, though the deadline was extended. Puciloski’s letter promised “a better, improved campground in 2023.”

The reaction among longtime Prospect Lake Park patrons was shock, concern, and the dispiriting expectation of soon being priced out of an important and longstanding part of their lives. Aside from the 90-day deadline to relocate their campers and belongings, some told The Edge they felt the abrupt announcement via an attorney’s certified-mail letter showed little concern for the people and community that had grown up around the campground over multiple generations.

One person associated with the campground for decades and who asked for anonymity to speak freely said summer residents were immediately worried they wouldn’t be welcomed back—even after Palmatier told them Rasch planned to maintain the property in much the same fashion.

“The campers couldn’t understand why if it was going to reopen as a campground, they couldn’t just move their trailers to one of the back fields, and be happy to pay for winter storage,” this person told me. “But the fact that everyone was given a pretty quick deadline to have everything removed led to a lot of questioning and confusion about what the real motives were.”

This person acknowledged that some of the facilities, including the bath house, were “dated,” and heard reports that an insurance company or the state wanted upgrades made. Still, they said, that didn’t seem to justify removing everyone’s belongings. “It was explained that ‘we need to put in new electrical lines and dig ditches and we may be reshaping the shape and size of the [camping] sites’ and that sort of thing. And that’s perfectly understandable,” the person said. “But when they weren’t even interested in letting the campers pay for camper storage back in the field, everyone got a little suspicious.”

This person, and others, requested anonymity because they still hoped to be able to return to the campground when it re-opened. They didn’t want their comments to antagonize the new owner.

At the time of his attorney’s letter, Rasch said in a statement to The Edge that he would assist anyone who needed help relocating their campers, and he told me last month that he had. “We helped everyone,” he said. “We either bought their trailer or gave them some financial resources to relocate [it].”

He told me there are affordable campgrounds nearby, pointing to those in Spencertown and Copake, N.Y. where he said some had relocated. (Calls to those campgrounds confirmed that at least a few former residents of Prospect Lake Park spent the 2022 summer there.)

“No one was displaced in the sense that these were people’s homes,” Rasch suggested, perhaps undervaluing how Prospect Lake Park was viewed by a community built up there for a half-century. “This was a recreational summer venue for people.”

So, what’s his plan for the property? “Basically, the campground is going to continue to be a campground,” he said, dismissing long-simmering social-media speculation that he planned to build condominiums or large houses.

But it’s clear that when work is completed in 2024—not next summer, as suggested in Puciloski’s letter—it will be far different and more expensive than what locals and tourists have enjoyed at the property during its history as a park and campground.

While Prospect Lake Park featured 125 camping locations, many with electric, water, and sewer hook-ups, Rasch’s new venture will only have 40 sites. And most significantly, gone will be the opportunity to park your own RV or camping trailer at the campground for short-term or May-to-October seasonal stays.

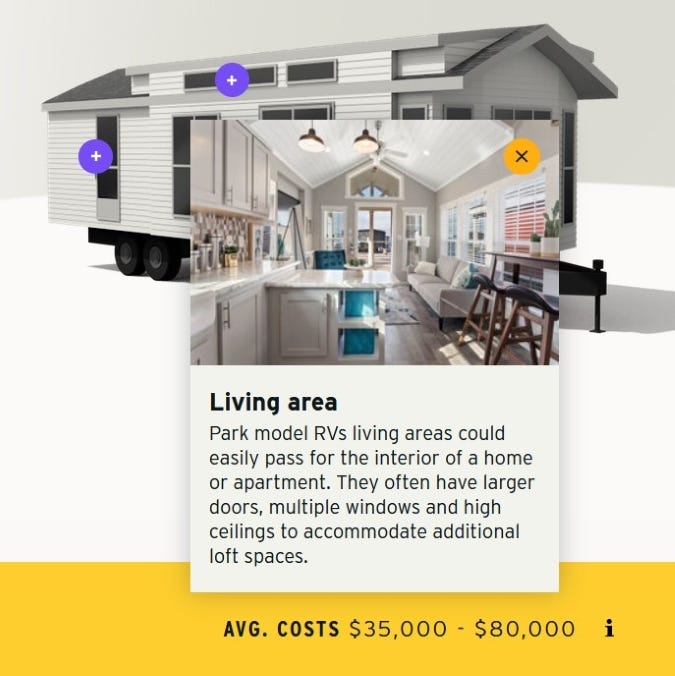

Instead, Rasch told me, his company is building “park model RVs,” which may look to some like tiny houses on trailers but which are considered RVs. They are built on a single chassis and mounted on wheels but not as easy to relocate as a more traditional RV.

“It’s going to be a different place, but it’s still going to have RVs. We’re just building the RVs,” he said, leaving me to parse those two sentences and compare that information to what is commonly understood to be RV camping. “They’ll be built under the park model RV code,” he said, to ensure the project comports with fire, life-safety, and public-health regulations as well as zoning pertinent to the longtime use of the property as a campground.

While Massachusetts has no statutes regulating park model RVs, the units are subject to federal requirements. They can contain no more than 400 square feet of space and be no wider than 14 feet. According to a description on the RV industry’s marketing website, park model RVs “are designed to look like a home” and are “built with wheels so that they can be easily moved into and around campgrounds.”

The wheels make the unit an RV, but they are not often moved. “Once hooked up to the campground’s electricity, water, and sewer, park models generally remain on the selected site year-round,” the website explains.

Andy Zipser, a former Wall Street Journal reporter who in retirement spent eight years as an RV park owner in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and wrote about the experience in his book, “Renting Dirt,” recently called park model RVs “one of the camping industry’s biggest con jobs.” He suggested they shouldn’t really qualify as regular RVs for legal and zoning purposes.

In a column he wrote in April for RVtravel.com, he detailed the ways the RV industry has successfully, over decades, nudged the definition of “RV” to be nearly the same as a small home, but just barely under limits that would subject them to regulation by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

He points out that in addition to convincing HUD to exempt “small lofts”—common in park model RVs for sleeping bunks, and which have grown steadily larger—the industry successfully lobbied to exclude the square footage of decks and porches attached to the chassis from the square-footage limit.

When I spoke to Zipser yesterday, he helped explain how park model RVs fit into the landscape of both RV camping and, increasingly, housing. “In every way except for the fact that they’re on wheels, they’re basically indistinguishable from a regular cabin,” he told me.

Told about Rasch’s plan, Zipser, whose writes about all facets of the campground and RV business with the depth and clarity of a longtime journalist, said, “Basically what he’s doing is creating a lakeside cabin community. And the cheapest way to get those cabins in there is with these park model RVs.”

Not surprisingly, the industry doesn’t see it that way. Jeff Sims, who serves as senior director of state relations and program advocacy for the National Association of RV Parks and Campgrounds (ARVC), told me that park model RVs are an important part of the universe of campgrounds and outdoor recreation. “ARVC supports park owners’ right to place recreational vehicles on designated sites. And a park model RV is a recreational vehicle,” he said.

He conceded they don’t look like what many people consider to be RVs. “To the untrained eye, when you walk in, the first thing someone might say is, oh, wait a minute, that’s a little manufactured home. And I get that,” he said. But Sims told me that there’s “a clear and bright line” that exempts them from HUD regulations and qualifies them as an RV. As to the build quality of typical park model RVs, he said they all must meet a variety of fire and life-safety requirements.

To stay on the right side of that line, he said that transportation equipment that’s part of the unit has to remain with it. “If you start removing wheels and axles and setting them on foundations, you are no longer going to fall under an exemption of a recreational vehicle,” he said. But to Zipser’s point, that distinction seems almost meaningless.

Sims said that park model RVs are a growing segment of the industry. “What it does is provide an opportunity for someone that doesn’t have a recreational vehicle to still enjoy the atmosphere and ambiance of an RV park without the investment,” he said, participating in outdoor activities and other amenities at RV parks.

First as a campground operator for 40 years in Branson, Missouri, and now in his travels with ARVC, Sims told me that he’s visited more than 2,500 campgrounds. “I’ve never been in one that looks just like the one right beside it,” he said. He’s not familiar with Rasch’s plans but said that if a park is being created exclusively with park model RVs, it’s likely to be “a significant investment” and “a top-shelf operation.”

To design his structures-on-wheels for his new hospitality venture, Rasch is working with Garrison Architects, an award-winning Brooklyn-based firm widely known for innovative prefabricated modular structures. Garrison describes its work as “pair[ing] a research-driven approach to design with highly refined modernist aesthetics.” Its website features at least one design for something resembling a small park model RV.

He also told me that he’s collaborating with Garrison’s architects on a related “research-and-development” project: a roughly 500-square-foot prefabricated, possibly fully-off-the-grid unit that he imagines could be sold to homeowners as an accessory-dwelling unit and help add to the region’s housing inventory. Or become the basis for a small-cottage community he said he’s considering for the top of Railroad Street in Great Barrington, just across the railroad tracks on a currently undeveloped parcel owned by another local developer. It’s located almost directly behind Rasch’s 47 Railroad mixed-use complex.

Rasch said he may reserve some sites at the redeveloped park for traditional camping, either on raised wooden platforms or with an open A-frame structure. But, as longtime Prospect Lake Park patrons had feared, there will be no sites for seasonal campers arriving in May with pop-ups, camp trailers, or RVs (as they’re more traditionally understood).

As for length of stays, Rasch said he’s exploring various options. “I’ve had a lot of interest from people who say ‘we’d love to rent one for a summer’ or ‘we’d like to rent one for a month.’” But it will no longer be a place for those looking for more traditional, and affordable, summer camping and swimming. He said it’s “unlikely” that the renovated park would be open year-round.

Given how this venture differs from his construction and property management businesses, Rasch said it will be managed by two people with long experience with these kinds of projects, though he declined to identify them. “Coming from New York, we established some very solid relationships with hospitality folks. My wife was very much involved in the hospitality world in New York for a while before she got involved in design,” he said. “So we’re not going to be doing this entirely on our own.”

But he sees some connections between his other properties and the campground. “Where housing stops and hospitality begins is becoming very morphed,” he said. Rasch had talked previously in our conversations about residential tenants who might need or want additional services, and suggested there’s some coming together of these worlds.

As another indication of the dramatic changes coming to the property, and the likely clientele, Rasch said he’s working with LAND, an Austin, Texas-based design firm, to create a new brand identity for what used to be Prospect Lake Park Campground. He told me that “LAND is very selective” about the projects it takes on. Indeed, its clients include premier brands like Apple, Nike, Vans, Patagonia, and Hermes.

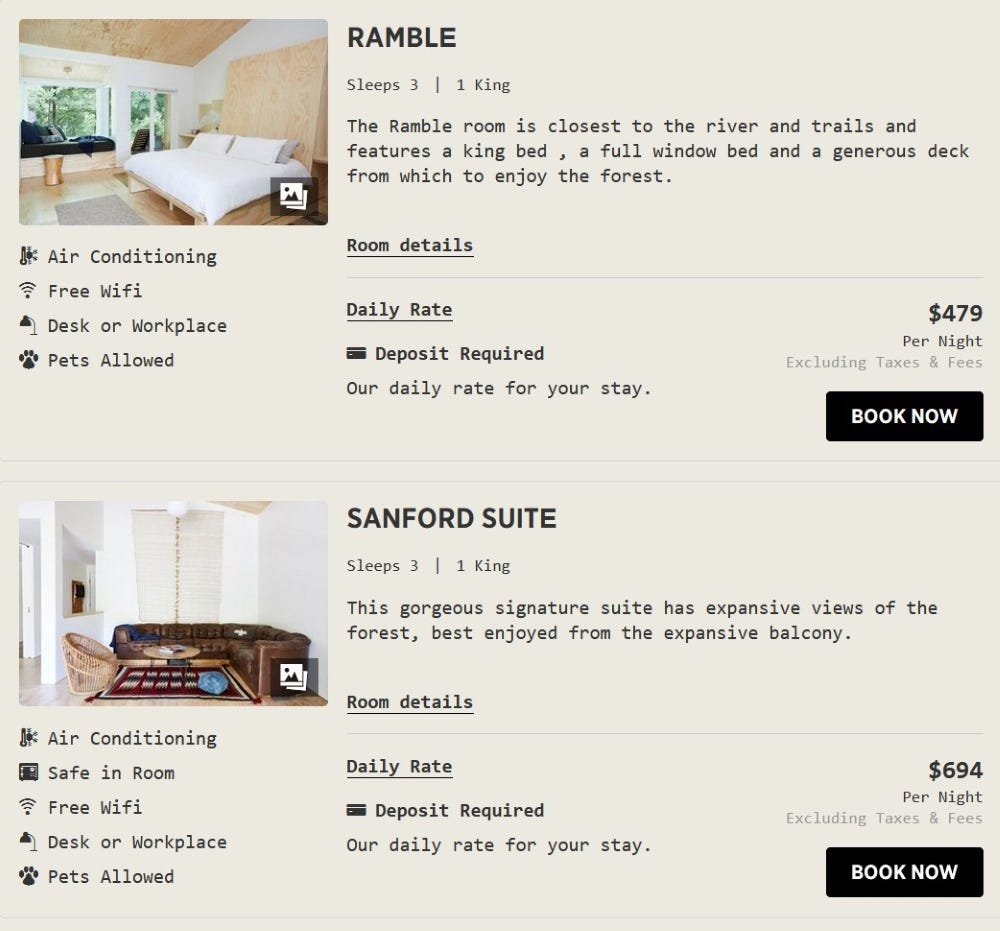

Perhaps relevant to the market positioning of Rasch’s venture, LAND was involved in the 2018 launch of Tourists, the North Adams motel-turned-boutique hotel where airy, minimalist-but-beautiful rooms, nestled into natural surroundings, rent for roughly $300 to $700 per night.

“Our 48-room property is a union of design and nature, home to woodland trails, riverbank vistas, sculptural installations, and more,” the Tourists’ website explains. “Using common, organic materials, your room is both haven and trailhead, connecting you with your vacation self and serving as a basecamp for adventure.” Conde Nast Traveler, the magazine of luxe vacationing, summed up its review of Tourists this way: “If you’re visiting this corner of the Berkshires, there’s nowhere more stylish to stay.”

Tourists also features common buildings for guests to meet and relax that could be comparable—in function, if not design or amenities—to Prospect Lake Park’s Cliff House, the original historic structure on the campground property, and its Rec Hall barn, which along with two other buildings will undergo significant renovation, Rasch told me.

By comparison, the former Prospect Lake Park described itself this way: “Located in the scenic Berkshires region of Massachusetts, Prospect Lake Park is a destination that appeals to all campers […], set along 2,000 feet of wooded lake shore and offer[ing] 125 shaded or sunny campsites. The campsites accommodate everything from the smallest tent to the largest RV (36’). […] Each site comes complete with picnic tables and fire rings for your cooking, eating and storytelling pleasure.”

Daily rates for campsites with water, electric, and sewer hookups started at $39.00, with seven small cabins available at weekly rates of $410.00 to $510.00. Season-long rates averaged $2,500 per year.

Rasch’s plan also includes a substantial ecological restoration of the entire property. After winning fast approval from the Egremont Conservation Commission in two separate hearings this summer, his team removed nearly 100 trees, some dead or dying, to thin the property’s monoculture pine forest and make room to reintegrate native tree species.

Several ecological-restoration consultants—BioHabitats, based in Baltimore; landscape designer and Project Native founder Raina Weber, and Philadelphia ecological-design firm Andropogon—are working on plans to reintroduce native plants and restore the property’s original habitats and ecology. “Instead of a free-for-all as it’s been for 50 years, we will take a lot of care,” Rasch told the commission.

Two of the three beaches on the property will be allowed to “rewild” as part of what Rasch told the commission in August will be “a comprehensive restoration plan that will focus on the lake edge … removing things like the old slide and sandy beach and instead placing boulders and native species to provide protection to the water’s edge.” The remaining beach area will be reached by “guided paths” that people can use to approach a possible lake edge “lookout area,” but he told the commission there will be “no direct swimming areas” from the shoreline. Access to the water for swimming will be via new piers that bypass the weeds and mud closer to the shore, Rasch told me.

Promised upgrades to electric, sewer, and water infrastructure are underway following approval of work inside the lake’s environmental buffer zone.

Rasch’s reaction to criticism that he’s buying properties across the region that formerly provided affordable options and transforming them into something exclusive and expensive is now standard: The campground, just like aging downtown buildings, needs substantial investment. And the only way to pay for that investment is to charge more, he argues.

He told me that his competitive analysis of campgrounds in the region confirmed that Prospect Lake Park “was by far the cheapest campground. But again, part of that was by virtue of the fact that the Palmatiers just never did anything” to upgrade the facilities. “It’s the same issue with these buildings. Yes, you can do nothing for a period of time, and everything can deteriorate. And then at a certain point, you have to make some type of investment.”

Regarding the electrical upgrades now underway, and noted in the letter sent last winter to seasonal campers, Rasch said, “I walked onto that site with an electrician and representatives from National Grid, and they walked away, got back in their trucks and said, ‘This is really scary.’ There were electric meters all over the trees. I mean, it was a significant hazard.”

He went on, “So, yes, there’s this romantic idea that this was an affordable campground, but the utilities were basically shot. And from a public-health perspective, many of the seasonal [campers] were in such bad shape that, I mean, they were filled with mold and filled with mice,” he said.

He estimated that 30 percent of the seasonal campers at the park when he took ownership were scrapped rather than relocated. “They were so disgusting that you couldn’t do anything with them. And yet we still offered some sort of financial remuneration,” he said.

Several longtime Prospect Lake Park patrons that I spoke to this fall, including the former owner, strongly challenged that characterization of seasonal trailers, while also acknowledging that the park’s infrastructure needed work.

Juliette Haas, director of the Egremont Board of Health, told me via email last month that the campground was inspected each year in order to receive its permit to operate. Inspectors from the Berkshire Health Alliance, a group of 24 municipalities that share public-health staff and services, performed the annual inspections and confirmed to the board that there were no issues with the facility’s main lodge, bathrooms, showers, or restaurant kitchen. Signage at the beach was also checked to ensure it met code requirements.

Haas said there were occasional complaints from a former campground neighbor about smoke from campfires, odor from the septic system, and allegations of illegal burning, but no violations were found. She said there were no health or safety inspections of private camp trailers, even if left on-site year-round.

Egremont Building Inspector Ned Baldwin told me last month that he did not conduct any annual inspections of the electrical or other systems at the campground.

When I called former owner Jim Palmatier last month at his new home in North Carolina and described what Rasch shared with me about his plans for the park, his point of view was clear: That’s not really camping.

Palmatier told me that he received immediate and negative feedback from his former customers when they received Puciloski’s letter last winter. He said he had no idea that Rasch would remake the property so extensively, and that Rasch told him he planned to continue the campground largely as it was but with some infrastructure upgrades.

“We had a family meeting with [Rasch] one day, my one daughter and husband from North Carolina, me and my wife,” Palmatier said. “And he assured us that it would stay a campground in the present state that it was at that point. It was a campground. And what he’s doing is not really a campground.” When I asked if there had been more specific conversations about improvements or changes, Palmatier said, “He said he was going to upgrade the cabins. They needed some updating, and he was going to update them. And that was all he ever said about anything being done on the property.”

Still, he acknowledged there were no guarantees, contractual or otherwise. “Once I sold the property, the man has the right to do whatever he wants to do, but he should have just been upfront,” he said. Considering the flack Palmatier took from longtime summer residents, his view of Rasch isn’t surprising. “The only thing I could say is that [Rasch] kind of duped everybody on what he’s doing,” he told me.

Palmatier, who is 73, has been recovering slowly from a near-fatal case of COVID he contracted last November. “They gave me kind of last rites, and I’m happy to be on this side of the grass,” he said. It may have been a significant reason for the ultimate sale, he said. “If that didn’t happen, we probably might not have sold the campground.”

Given that he operated the campground with little staff, his age and health issues were likely the final nudge. “You know, I can’t do what I used to be able to do. I’m not a young boy but I worked like I was 20, even being in my 70s,” he said. “When we moved down [to North Carolina] in January, I couldn’t go up a flight of stairs. Right now for me to hold down a normal job where I have to exert myself? I can’t do it.”

Palmatier spent decades as a parts manager at auto dealerships largely in Newburgh, N.Y. When I asked him what inspired him to buy the campground, he described his introduction to camping.

“One of my workers said, ‘let’s go camping.’ I told him he was nuts. That’s about 28 or 29 years ago,” he said. He soon bought a pop-up camper and started looking around for places to visit. “One of our first places we went camping was Prospect Lake Park and it always stuck with us. I told [former owners] Sandy and Mary Mason if they were ever going to sell to let me know.”

He enjoyed his years running the park. “It served our lifestyle very well and gave us the opportunity to enhance our lives. You know, being able to sit around and bullshit at the fire and have a drink or two and get to know new people. Everybody’s so gracious. You know they’re so happy to be out there camping.”

He said that he watched a lot of people grow up, get married, start families. “We saw families come in that probably had five, six children. They came in [first] with no children,” he said.

Overall, Palmatier called the campground “a little slice of paradise.”

On its condition when it changed hands, Palmatier told me that electrical-infrastructure improvements planned by National Grid a few years ago were put on hold by the pandemic. And any electrical problems some visitors experienced, he said, were related to the greater demands of modern camp trailers and RVs. That suggests, as Rasch described, the need for upgrades.

“The electric was more than adequate as far as I’m concerned for what we were doing. We were an old campground, mom-and-pop-type operation,” Palmatier said. “The newer campers, compared to what they were 10 years ago, you need twice the amount of power to run. Older campers running on 30 amps, new ones with three air conditioners, microwave, TVs, need 50 amps to run. It’s kind of difficult to give them that kind of power,” Palmatier said. (Campgrounds across the country are currently grappling with what electric upgrades may be necessary to accommodate charging of electric vehicles and RVs, Zipser told me.)

As for the condition of seasonal camping trailers, Palmatier said there could certainly be one or two that had issues, but he generally required them to be repaired or upgraded. Otherwise they wouldn’t be permitted back the following season.

Several former longtime residents noted Palmatier’s work ethic, and also suggested that the campground may have been understaffed compared to how previous owners ran the operation. Some acknowledged he could sometimes be gruff; indeed, online reviews suggest that customer service at the park was underwhelming in recent years. Still, those who returned year after year describe a community of people willing to chip in and help Palmatier keep the place running.

“I couldn’t ask for better people to help me, some of my seasonal campers over there, and if we ever had a problem or catastrophe of any sort? I didn’t have to ask, they just pitched in. They were happy to do it,” he said.

While Rasch’s new venture is clearly aimed at a different clientele, he told me that he’s committed to working with the Egremont community on several fronts. That includes lake access and parking.

“We’re going to create public access to the lake where people can come and walk around and have access,” he said, describing nascent plans to create what he said would also be some “limited” public parking. “And so [people aren’t] parking right on the side of the [Prospect Lake Road] and terrified that they’re going to get hit by a car.”

If he follows through with something substantive, that’s not an insignificant proposal. There have long been safety concerns around lake access on the southeastern shoreline via what’s known as “The Gap.” It’s located on Prospect Lake Road immediately around the corner from the entrance to the former campground. Swimmers and boaters commonly park cars and trucks along the north side of the street, narrowing the roadway for automobile traffic and creating hazardous conditions for pedestrians. Furthermore, the two breaks in vegetation at The Gap that give access to the water require walking down short, steep paths. That creates accessibility challenges.

There’s no other public access to the lake. A former boat launch on the southern shoreline on land managed by the Massachusetts Department of Fish & Game fell into disrepair and was removed. Because of Fish & Game regulations, entry from that location for swimming was not permitted. Nor is it possible, given the conditions at that location, which can no longer accommodate boats.

Meanwhile, with substantial redevelopment work to begin shortly on Routes 23/41 through downtown South Egremont—an $8 million road-and-sidewalks project from Creamery Road to the intersection at Smiley’s Pond to the west—cut-through traffic on Prospect Lake Road is likely to increase through next summer. That creates additional urgency to address lakeside hazards.

Earlier this year, Egremont’s Prospect Lake Access Committee, established with a small grant from the Massachusetts Department of Health, explored options to address these longstanding issues around safe lake access. The Gap is on privately owned land, though because of the lake’s designation as a Massachusetts great pond—one that has more than 10 acres of surface area in its natural state—the public is allowed to cross undeveloped private property to access the water. According to the access committee’s final report, no progress was made during conversations with the owner of the narrow strip of lakeside land.

So, last spring, the Egremont Select Board authorized a filing in state Land Court to secure a prescriptive easement. That could legally formalize decades-long public access to the lake at The Gap, if not entirely address safety concerns on its own.

And back in May, the administration of Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker surprised the town with an earmark of nearly $1.2 million of American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds for construction of a new boat launch on Prospect Lake, potentially adding new resources and an opportunity to create broadly accessible lake access.

Unfortunately, the legislature failed to pass the ARPA-related economic-development legislation at the end of its session in July. By then, though, the specific ARPA earmarks had been stripped out, including the allocation to Egremont. Some version of the legislation will be reconsidered after the election.

The Lake Access Committee was not empowered to talk to other property owners, including Rasch, so it’s unclear at this point how his plans or proposals will mesh with other efforts underway on lake access and safety. But there seems to be a clear alignment of interests and an opportunity to collaborate.

Beyond parking and some kind of public access, Rasch said he also wants to make the property “a community resource,” perhaps by providing free access to Berkshires residents for a couple of weeks in September and offering facilities for events and conferences.

“We’re going to provide options for local nonprofits to use it for free. We’re going to balance the required capital [investment] to bring this place back up, so it can actually function and be safe and be fun and a recreational park, but also provide access to local residents,” he told me. “I think that’s a fair and practical way to address these things.” If that materializes, including Rasch’s nod toward providing some free access to the shoreline for the public, it would go beyond what was offered there under previous ownership.

As with his Mahaiwe Block and 343 Main Street projects, Rasch seems largely unmoved by criticism of his plans, suggesting that most people don’t understand what’s involved. “‘Oh, my God, he’s killing the last affordable campground,'” he said, repeating what he’s heard since last winter. “I mean, there’s a lot to that, you know, in that it was unsustainable, and that’s why the Palmatiers sold it. I mean, it needed a huge amount of investment, and they couldn’t deal with it.”

Comparing the project to his coming redevelopment of the Mahaiwe Block, he said, “We become the stewards of these properties and these buildings. Yes, you have to raise rents, but you have to make a huge investment.”

Some former seasonal campers told me there was never any serious consideration of purchasing the campground from Palmatier, largely because they assumed that any new owner would keep the park as it was.

There’s a healthy debate to have about whether needed investment in an aging building or a campground with infrastructure needs means the only available option is to create high-end amenities at high-end prices for the numbers to pencil out, to use the popular term of art. When profits and investor returns are the goal, that’s certainly an operable and explainable position. But there’s a broader and vital conversation needed about how and where public investment—and at minimum, much better public policy—can bridge the gap between private interest and community goals and priorities. That’s obviously more true for housing development than for privately owned campgrounds, but raises questions about preserving, or even expanding, vital commonwealth.

There are other evolving models for campground ownership and investment. Trends that began mid-pandemic showed an increase in outdoor-recreation vacations, from tent camping to trailers to all flavors of glamping—but particularly for RV camping, which is considered by many to be a safer option in the COVID era. It’s also become a popular and flexible remote-work option.

So, it’s no surprise that private equity has joined the party. And not just in one-off projects like Rasch’s—which, like his residential-apartment and commercial-property acquisitions, is financed with both debt and private-equity investors.

For example, in early 2021, a new enterprise called Spacious Skies began acquiring campgrounds across the country, promising upgrades, centralized booking, professional corporate management and the efficiencies of a larger enterprise. The company purchased nearby the Woodland Hills campground in Austerlitz, New York and folded it into its rapidly expanding portfolio; it now has 15 campgrounds. And earlier this year, Sculptor Capital, a large real-estate private-equity fund, became an investment partner in Spacious Skies, just as other firms have become involved in the market.

Whether this means the end of an era for unique, mom-and-pop campgrounds with distinct and longstanding communities like Prospect Lake Park remains to be seen. Eric Rasmussen, who along with his wife Ali started Spacious Skies, told Woodall’s Campground Magazine in May, “We are encouraged by the demand tailwinds and consolidation momentum we continue to see in the industry,” he said. “We are singularly focused on providing authentic outdoor experiences to our customers.” (Label me weary of investor-oriented marketing language: “Providing” something “authentic” seems counterintuitive on its face.)

With some campgrounds adding upscale amenities and shifting to a mix of higher-priced glamping options alongside traditional RV trailer camping, some limit the age of camp trailers and RVs allowed into their parks to no more than 10 years. There’s even a Facebook Group with more than 11,000 members called “My RV is Too Old for Your Park.”

In fairness, older campers and RVs can bring issues that create headaches for campground owners and for other guests. And most campgrounds will evaluate older RVs and campers on a case-by-case basis. (That is, evaluate the campers’ RVs, not evaluate the campers themselves. But perhaps that’s a distinction without a difference?)

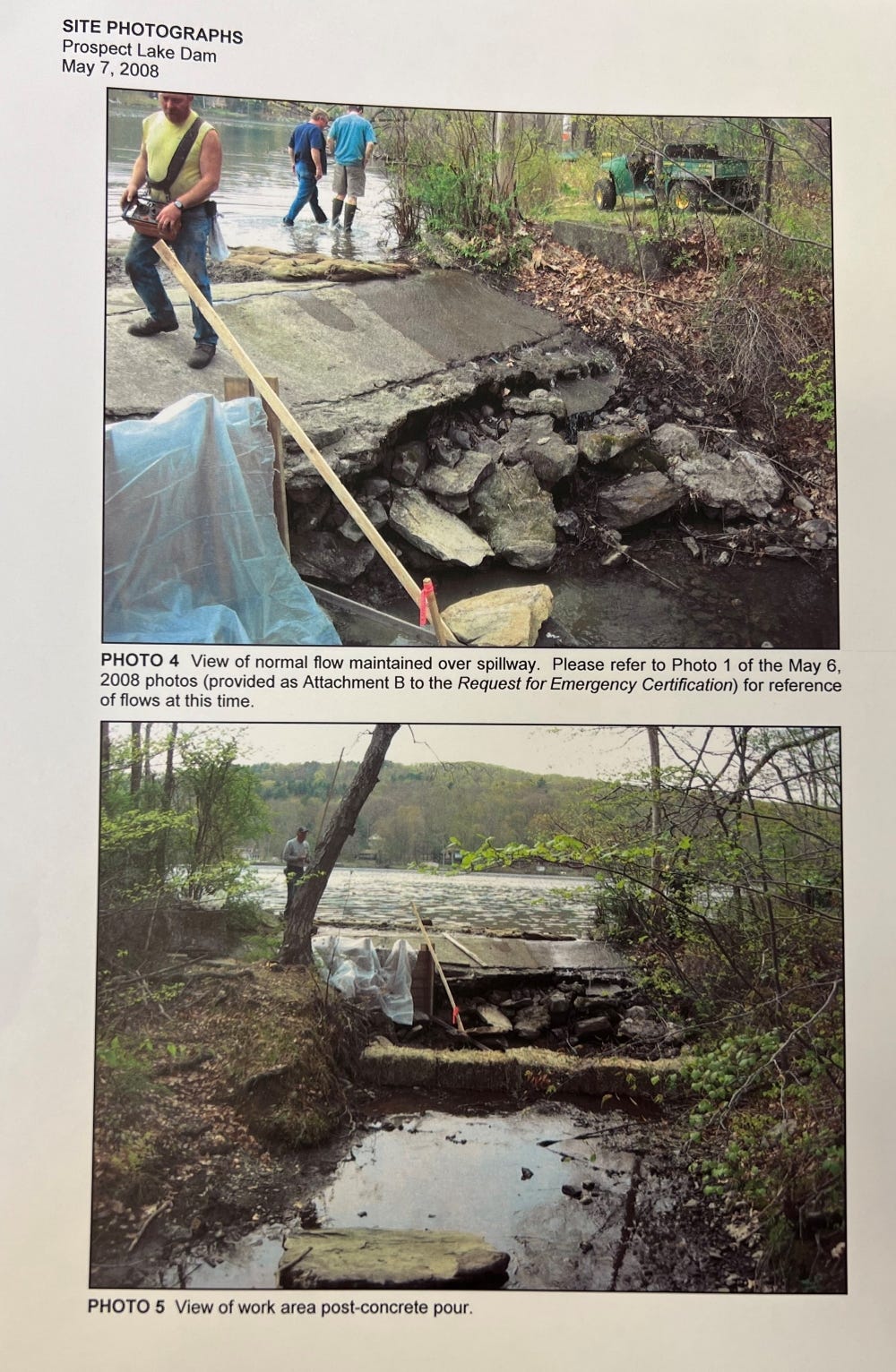

There is one element of the Prospect Lake Park campground that may explain why it might have been a hard sell to potential buyers who don’t have Rasch’s resources and commitment. And that’s the crumbling, 300-foot concrete dam on the northern edge of the campground property that makes Prospect Lake what it is.

Without the dam—or if it fails—the lake would be four or five feet lower and more likely to be overtaken by weeds and face eutrophication. In other words, the lake could die—or, at minimum, become far less appealing.

The dam has been in significant disrepair for decades, with a lower-level outlet once used to draw down the lake in winter entirely nonfunctional. The dam’s concrete abutment walls are crumbling in places. Since at least May 2008, when emergency repairs were made, the dam has been considered by the state to be a “significant risk.”

The state’s Office of Dam Safety, part of the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), has over the years sanctioned Palmatier for not properly maintaining the dam and failing to file required reports on its condition. In a 2008 letter, just prior to emergency repairs, it said the dam “does not meet accepted dam safety standards and is a potential threat to public safety.”

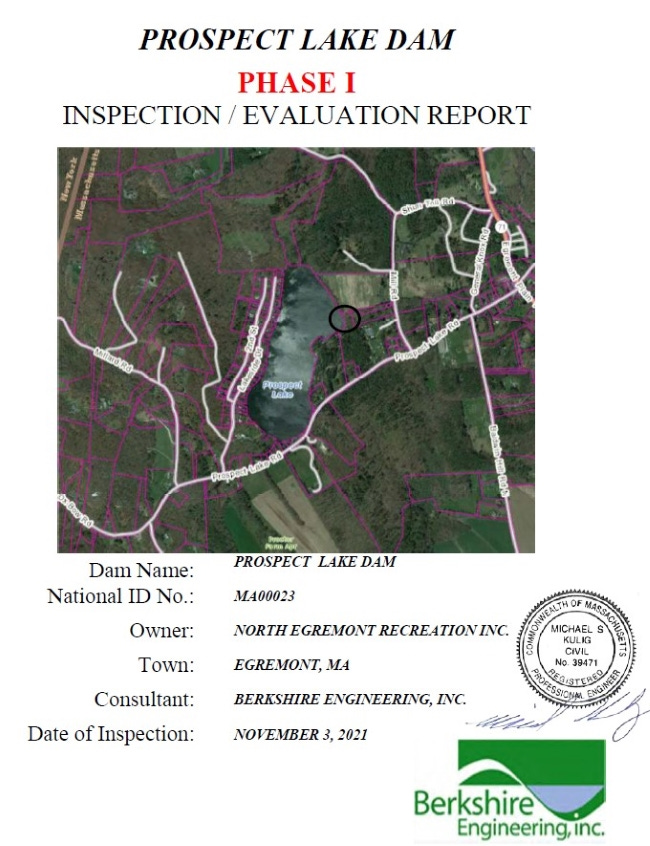

In November 2021, shortly before selling to Rasch, Palmatier hired Berkshire Engineering to conduct a detailed assessment of the dam. (These assessments are legally required every five years.) That report confirmed that serious problems remain—if not any more significant than what was found during a previous evaluation in 2015.

Still, engineer Mike Kulig concluded, “It appears that a failure of the dam at maximum pool will have potential to cause loss of life, cause damage to home(s), secondary highways, and/or cause interruption of the use of service of relatively important facilities.” A failure of the dam could quickly flood an area of 1.26 square miles.

With the sudden overnight failure two weeks ago of an earthen dam in Hinsdale, which mercifully left no one injured or killed, there’s new attention being paid to approximately 226 dams across Berkshire County.

And, relevant to Rasch’s purchase, questions about liability. Those questions are easy to answer: In Massachusetts, private dam owners are liable for any impacts from a dam failure. The relevant statute is unequivocal: “The owner shall be responsible and liable for damage to property of others or injury to persons, including but not limited to, loss of life resulting from the operation, failure of or misoperation of a dam.”

Without the ability to draw down the lake, which can help to curb weed growth in the shallow waters along the lake edge, Prospect Lake is chemically treated each year by Friends of Prospect Lake, a nonprofit organization formed in 2006, to support the lake and manage invasive weeds including Eurasian Milfoil. This has been controversial, as any chemical treatment is, though the work is regulated under an order from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP). While an annual draw-down of the lake might not fully eliminate the need to chemically treat, it may reduce the volume of chemicals used.

Rasch told me that he is well into the permitting process for needed repairs to the dam, which was confirmed by a spokesperson for the Office of Dam Safety. He told me that he initially expected work would cost around $100,000, a number significantly less than the “range of $200,000 to $300,000,” plus $30,000 in design and permitting, proposed in Kulig’s 2021 engineering study. (Kulig’s report noted that a full construction cost estimate wasn’t possible until additional work on permitting and plans was completed.)

Rasch told me that bids are coming in between $500,000 and $750,000. He’s exploring funding sources for the work, but some avenues, including money from the Army Corps of Engineers, is not available for privately owned dams.

“It’s unusual for a dam like this to be privately owned,” he said. And he’s right. This dam provides enormous benefit to the general public who use the lake, and adds significant value, monetary and otherwise, to those who live around the lake. Rasch told me that he believes the dam should be publicly owned, a change that would also open the door for to public funds that could pay for repairs and maintenance.

According to filings with the South Berkshire Register of Deeds, back in March Rasch separated a small portion of the campground property that includes the dam into a separate limited-liability corporation, Lake Dam LLC, cognizant of dam owners’ liability for any failure. It could also help lay the groundwork for an eventual sale of the dam to the town or state.

The danger from the dam has prevented Rasch from securing public-liability insurance, he told me. “Until that dam is replaced, we can’t actually get an insurance policy and cannot open up for business. Way too much of a liability,” he said. “I mean, if we have 60 people on that property and that dam, God forbid, collapses? I’ll go to jail.”

Back in April, the Conservation Commission reviewed initial plans for repair of the dam and attached conditions regarding removal of invasives and a plan for replanting native species after construction. The next public phase of the project will be the Commission’s approval of the details of Rasch’s ecological restoration plan for the entire property, expected this fall.

Meanwhile, as longtime Prospect Lake Park summer residents begin to take in the news that they can’t return, it’s fair to consider whether Rasch could have been more transparent about his plans. When his attorney promised “a better, improved campground in 2023,” he and Rasch could have, and should have, shared that the new venture was not going to welcome back seasonal campers.

He’s to be applauded for any assistance he provided to those who had to relocate their belongings, in some cases from a distance. Yet whatever logistical or financial help Rasch offered shouldn’t obscure what should have come alongside it: clarity, transparency, and honesty. Just as Mahaiwe Block tenants spent the better part of this year without details of what might happen to their housing situation, many people who built their lives around summers at Prospect Lake deserved to know. Frankly, the human element seems to have been too casually left out of a series of financial transactions. That’s our economic system, perhaps. But more should be demanded of it.

Rasch’s argument on the path forward for a campground is similar to his thinking on downtown redevelopment: His approach is the only workable option. “It’s like anything. I mean, running a romantic sort of family-owned business today and operating on the same model that you did 30 years ago just doesn’t work financially,” he said. Yet there are thousands of campgrounds around the country operating as they have for decades, with modest improvements to stay up with the times.

What he said next was both interesting and revealing: “I also think people’s needs, tastes, and aspirations have changed. So it’s still a campground, it’s still going to be a campground. It’s just we’re trying to re-imagine that for today’s world of a population of people that [are] maybe looking for some other things.”

That raises a simple and urgent question that’s central to what’s been explored in this series: Which people?

NEXT: Where’s the action plan on housing? And why isn’t there one? In the final part of this seven-part series, a look at what we can learn from other tourism-based and second-home-heavy communities and how they bring together private developers, housing advocates, and government to make progress.

(This series first appeared in The Berkshire Edge.)